Three propositions about the current environment and three recommendations for improving dissemination of evidence

The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

I come from the planet cancer. My work there, I think, is conceptually relevant to the work that you all do. I’m an intervention researcher. We develop and test programs and solutions to try to eliminate health disparities in cancer. We create solutions for vulnerable populations to do things like change behavior, increase screening, etc.

And I’m pretty frustrated with that. I’m frustrated because we’ve developed over the last couple of decades lots of very promising solutions. And despite our commitment and best efforts to get those out into the world and into widespread practice, our best successes look pretty local or regional. And they are not doing enough to move the needle on public health. So we’ve tried to think differently about this. And I hope the ideas I’ll share with you today will supplement the very many good, important lessons that you’ve heard from many other speakers.

So, I have no disclosures, but I do want to acknowledge a handful of folks who have really helped me develop the ideas I’m going to share with you. Peter Hovmand, Jay Bernhardt, Chris Casey, and Jim Dearing.

Dissemination versus Dissemination Knowledge

Here’s a question for you. Multiple choice question: You’ve got to choose one of the two. The question is, which do you want? The top choice is more dissemination knowledge, and the bottom choice is more dissemination.

It’s kind of a false dichotomy, right? Everyone in the room would like both of them, probably. I want to declare my bias here. Which is, without hesitation I’d check the box at the bottom. The reason that I start with this is to make what I think is a very important distinction — we’ve heard at least four times today the difference between necessary and sufficient. Getting more knowledge about implementation about dissemination is probably necessary to get more dissemination. It sure as heck isn’t sufficient. And if that’s as far as we go with it — is to generate more research-based knowledge about the process of dissemination and implementation — don’t count on that delivering widespread use of what we’ve developed. That’s one point.

The second point, and I think this is much more important and it’s really the focus of the talk today — is that the activities that you take to get more dissemination and implementation knowledge are very different than the activities you take to get more dissemination. They are very different.

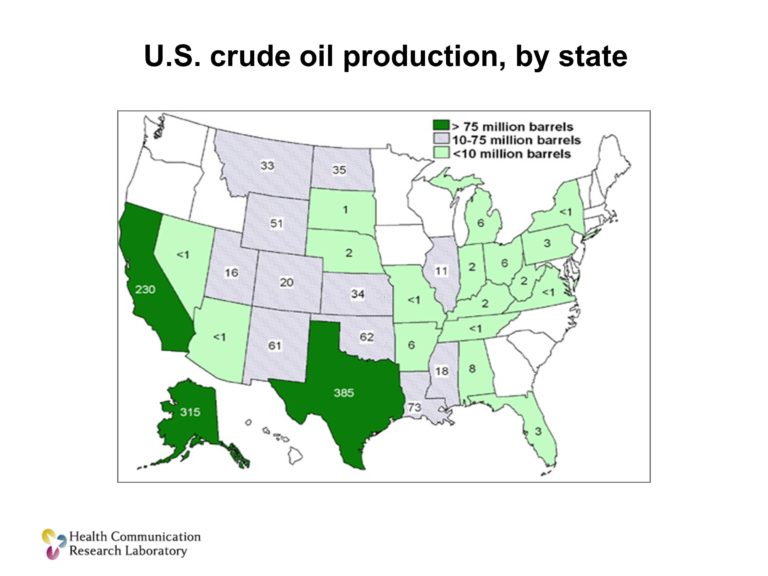

I want to illustrate this with this map. This is a map of crude oil production in the United States. There are a couple of states that are very dark green — Texas, Alaska, California. And this is a bright group of people. I could give you the challenge, I could say, let’s come up with a plan. Let’s spend some time thinking about how do we get this crude oil from the point where it’s produced in these oil production states to the refineries around the US so they can convert it into products that consumers can actually use. We could solve that problem conceptually here in this room. We could study it and figure it out.

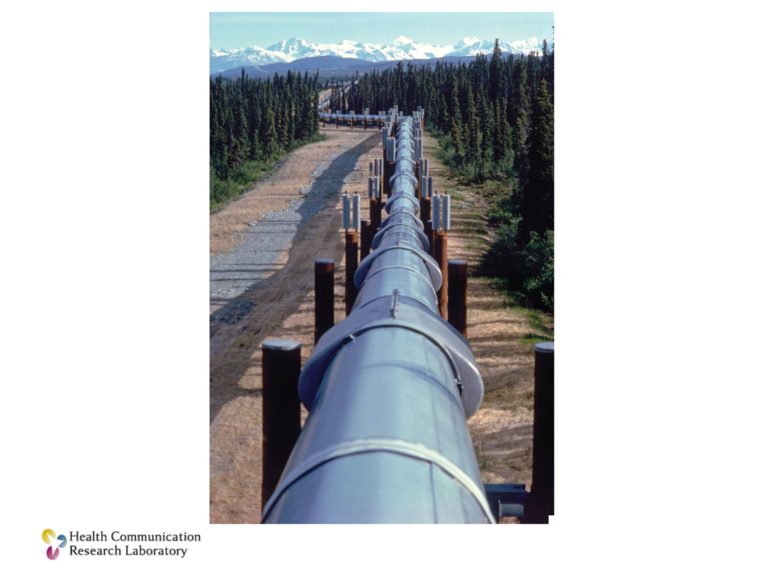

But at the end of the day, you still have to have one of these. You’ve got to have the infrastructure and the systems to move things from the point of development — crude oil in this case — to the point of use by other people. And this is the piece that in so much of our health research is absolutely missing. It’s not that we don’t do it well, it’s not that we’re not trying hard enough. We don’t even have it. We don’t have the infrastructure that we need, and without it, we’re going to continue to be frustrated at the level of uptake of our solutions.

I’m going to talk about, in my slides, programs. Because that’s sort of the language that we use — we develop and test programs. I’ve heard this morning treatments, I know some of you work in assessments that might come from this work. Or interventions. So when you see programs think about the work that you do in sort of applied research.

Here’s the talk. I’m going to go through three propositions. I’m going to try to defend those propositions. At the end I’m going to present to you a system that I think would overcome some of the important limitations that we have.

Three Propositions on Dissemination

Proposition number 1. And I apologize if yours is one of the programs that I’m talking about. But many, and in fact I think I could make a case that most, of the things that we develop as researchers — even the ones that are efficacious in rigorous research — are not worth disseminating.

And we have to accept that. And we have to do a better job of figuring out which ones are, and investing in those.

Why do I say that? Here are a couple of examples from domains outside of health and research. I think we should be looking to those for examples.

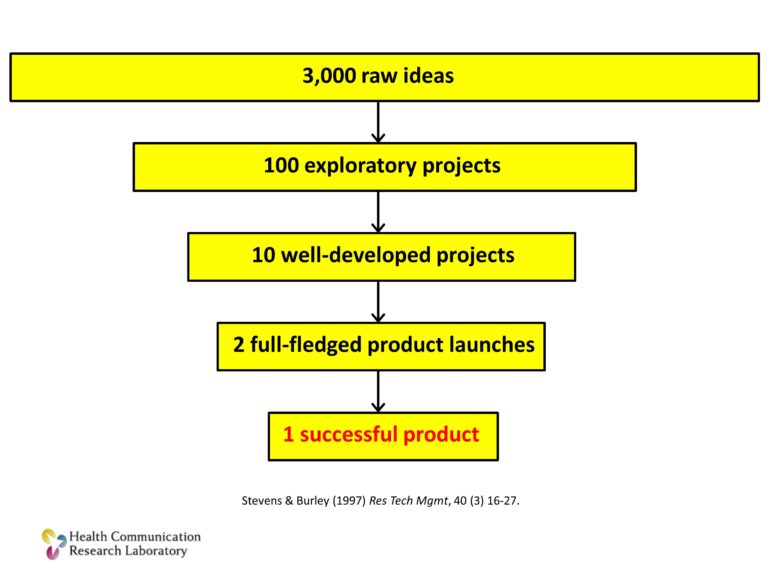

This is from a study of technology products and what actually makes it to the market. This funnel that you see starts with 3,000 raw ideas for technologies that could become products. That ends up becoming about 100 exploratory projects. Some of those — a small portion of those become well-developed projects. Just a handful, maybe one or two of those will be launched as products. One will succeed. Many worthy ideas. Many pilot projects. Very few successes.

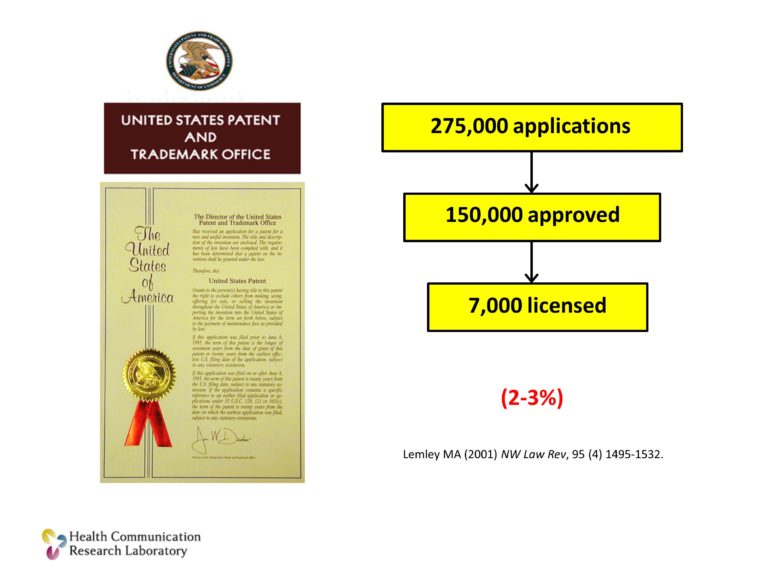

The same thing can be seen from US Patents and Trademarks. Over a quarter million applications per year go through the US Patent Office. About 60% of them are approved. A very small percentage — about 2-3% of those are actually ever licensed. Of those that are licensed, even fewer are actually used. Many worthy ideas, very few end up being used.

And the last example from our own work. This is a web-based, an online tool that we have: MIYO, it stands for Make It Your Own. It allows organization to create their own customized versions of evidence based communication tools for cancer prevention and control.

It’s being used pretty widely with about 500 organizations in all but one state. And we did a little case analysis in three of those states. We wanted to find out, why did people use it and like it.

These are the answers that they gave. The important point here, that I’m certain those in the back of the room cannot see, is that the fact that it delivered evidence-based tools, community-guide recommended evidence based tools, ranked 10th. It was the 10th reason that they used it.

What was above it? All sorts of things. It helped them solve a problem they were trying to address. It was easy for them to use. It gave their partners something that they value. It let them customize things for their local population.

Those were the reasons the liked it. The fact that it was evidence-based? Eh. Maybe.

Evidence-based matters to everybody in this room, as well it should. But we should quite pretending it matters as much to practitioners in the field as it does to us. It doesn’t.

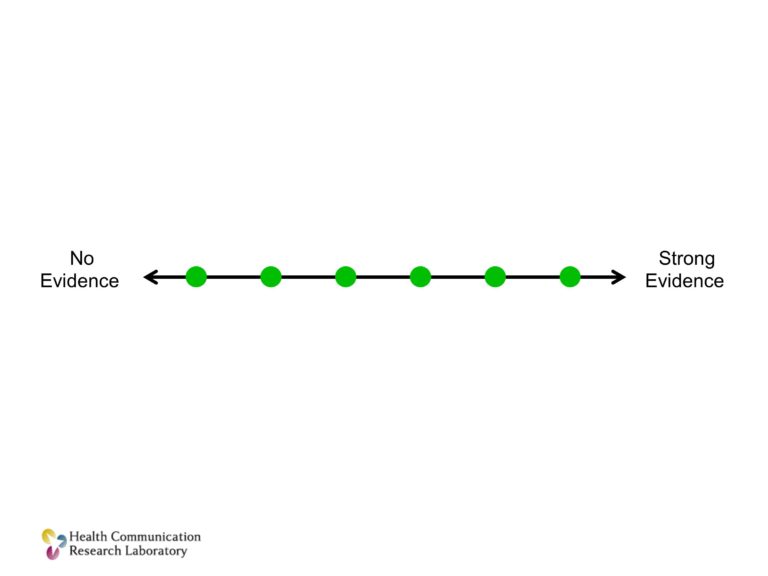

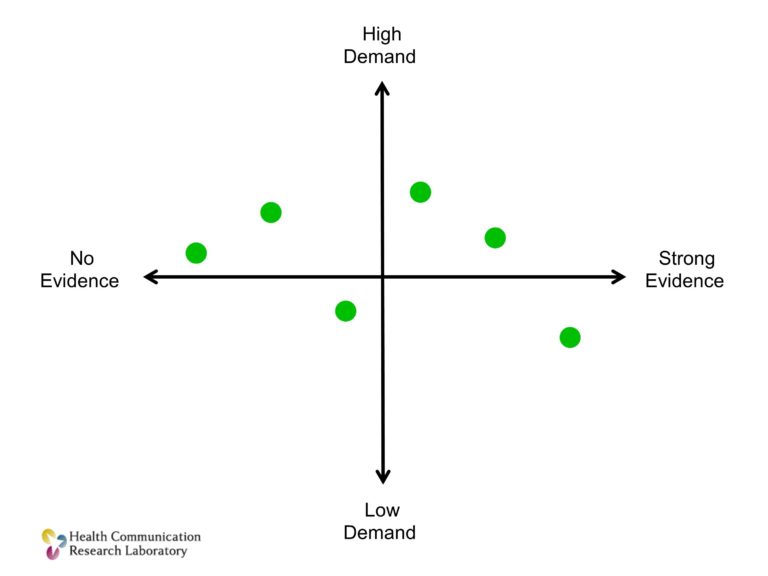

Think about this. Think about each dot on this line as a program or some sort of a solution. We like to classify these as scientists along a continuum of evidence. We like to know what has strong evidence and what has weaker evidence. Or, as we’ve heard today, we like to know for which of these do the benefits outweigh the possible costs of it. We can look at an evidence based continuum. Frankly this is what we do, and we’re very good at this as researchers.

But we need another dimension. A dimension that I’ll call demand. Demand is the demand from organizations that might actually use it. The clinicians, the practices, the schools. If you plot those same solutions along two axes, not just evidence but also demand, I can make the case that I’ll live with a little less evidence if there is high demand. If the goal is to get things into practice.

I believe you can refine and improve on efficacy. But you can’t magically create demand for something that people just don’t want. Or that doesn’t fit in the way that they are doing things.

We need not just evidence-based programs and solutions. We need evidence-based programs that are in high demand.

Second proposition. Most of what we do. Most of what we make and test in research isn’t ready for use in practice settings. Often it’s not even close to ready for use in practice settings. If we want it to be used in practice settings — let alone be used by many different, diverse populations in many diverse settings, we have to be able to adapt it.

I’m going to tell you the story of Newman’s Own dressing. Does anyone have some of this in their refrigerator? All right. Excellent.

The late Paul Newman knew his way around the kitchen. And one of the things that he liked making was salad dressing. And he made salad dressing in part because he was so unsatisfied with the salad dressing he could get in restaurants. He would go to restaurants with his wife, or they’d go out with friends. And it was so bad he would begin bringing his own little jar of his home-made, kitchen-made salad dressing. And you can imaging the reactions.

At first, the reactions from the people dining with him are embarrassment. “Oh, God. Newman’s got his jar out again.” Then they tried the dressing, and it was pretty good. And it was so good, they began asking him for it. “You know, would you make some for us?” Then one of his friends who had a business mindset said, “Dude. Sell it.” And so. Hence was born what we know as the Newman’s Own brand.

The Newman’s Own that is sitting in your refrigerators is not the same as the Newman’s Own that he would make in his kitchen and carry to the restaurant. It’s got some different ingredients in it. He’s got to stabilize those ingredients so when they sit on the delivery trucks and they sit on shelves they don’t completely separate or whatever it is you don’t want salad dressing to do. So he’s got to tweak it a little bit.

And then it’s got to be adaptive. Because not everybody wants or likes the same salad dressing that Paul Newman and his friends like. So you come out with variants of it, tweaking it for different populations.

I think you see the analogy. What worked? The evidence-based salad dressing that came out of Paul Newman’s kitchen had to be changed when it was taken to scale. It had to be changed for different kinds of users who would use it.

We have to be able to do that for our scientific solutions as well.

The third proposition, present company excluded, of course. Is that scientists who make programs, treatments, for the most part are really lousy at dissemination. The sooner we embrace that and accept it and stop pretending that we can become great disseminators, I think the field will be better off. Assuming we can partner with people who do have those skills.

I want to illustrate this point by taking you through what a marketing and distribution system does from the world of business. I think you’ll see very clearly how our operation in the scientific community holds true to a certain point. Then it falls off the map.

I want to show you what these systems do — they exist solely to take products and services from the point of development to the point of use. Which is what we’re trying to do with our treatments and programs.

Market Research

I’m going to use the example of the automobile industry. In the automobile industry, let’s start with some market research. There are people who are trying to figure out, what do consumers want? Do they want minivans? Well, not anymore — but do they want minivans? What do they want in a minivan? Should it have 18 or 25 cup holders?

Initial Design Concept

So they figure this out. They have some sense about what’s needed. This is very much like the surveillance that we do in our fields. It’s like audience research we might do around a solution. And then that information is turned over to somebody who comes up with an initial concept design for a product. This is us. This is the researchers in the room writing a grant proposal. I think I know what people want, I think I know what people need — I’m going to write it out — this is what we’re going to do, please give me money so I can do it.

Prototyping/Working Prototype

And then it gets funded, and they move forward. And it starts as a prototype. That prototype, if there is interest and success, becomes a working prototype.

Testing in Controlled Settings, Safety Testing, Road Testing

And that working prototype gets tested — first in controlled settings. Let’s see if it does the kinds of things that we think it will. Let’s makes sure it doesn’t hurt people. Let’s do some safety testing with it. And then and only then would we take it out into a real-world setting.

But it’s not a real, real-world setting. It’s not a real road, it’s a parking lot with some cones. And this is what we call and efficacy trial in our work, for the most part. This is our efficacy trial. And the car performs well in the parking lot. Our intervention does well in our efficacy trials. And we write it up, we champion it, we want and kind of hope people will use it. We submit it to one of the online databases that will allow people to access it, and we hope things that are good happen, and usually they don’t. Then we’re on to the next thing.

So the analogy works to this point. What I want you to see is everything that happens in the automobile industry after you get to this point. Because it’s dramatically different from what we do.

Tooling

So you’re going to take this pilot trial and you’re going to make it available to everyone. First you’re going to have to make some tools so you can produce it in larger numbers.

Mass Production

Then you’re going to produce it in larger numbers. With cars, these don’t roll off the assembly line and into your driveway, do they? No.

Distribution

They go onto trucks. Shiny red trucks. And the trucks take the products to…

Dealer Networks

Dealerships. That are located where people live. Near where people live who are going to be buying cars.

And they don’t trust that you’re just going to wander by, “Oh, look, there’s a car.”

Advertising

No, they advertise. They generate demand and drive you to the dealerships.

Showroom

And if you go to the dealerships you can actually see the products and talk to people who know about the products inside and out, and how they might work for you.

Test Drive

You can test drive them. You can try it out. Does this product work for me? You can give it a spin.

Standardized Information

You can compare the product to other alternatives that are on the market, using some standardized metrics.

Financing

If you decide to dive in, there are friendly — very friendly — people who can help you acquire the product.

Repair

If your product breaks, they have a whole industry of people who can fix the product.

Updates

If something new comes along with your product, they’ll let you know. Look, there’s a new version, there’s an update.

Building a Dissemination Support System

All of these functions are baked into the system. We have none of this, for the most part, in the world that we live in.

What are the key points to take away from this distribution model?

First of all, every one of those responsibilities is assigned. It’s somebody’s job. They wake up in the morning knowing that their professional identity is to drive the shiny red truck with cars. That’s their job.

Think about your identity as a researcher. Nobody, none of us wakes up thinking that they are going to do any one of those steps along the line. Even if they were, you’re not trained to do them very well.

Second point, specialization. The person who wrote the grant, who designed the car, is not the person who drives the shiny red truck, is not the person who repairs it when it’s broken.

Lastly, all of those functions, while they are specialized and assigned, they all work seamlessly together.

So, if we’re going to build a system that would support this sort of dissemination and implementation of our science, I think it has to do three things.

We first have to figure out what people want. So it has to be a demand-driven system, not just an evidence-driven system. It has to be a system that can take scientifically tested tools and adapt them so they are ready for practice and can be modified for different users. And we have to be able to promote the use of those and help people to use them.

So I’m going to address three additions to our current model that would accomplish this.

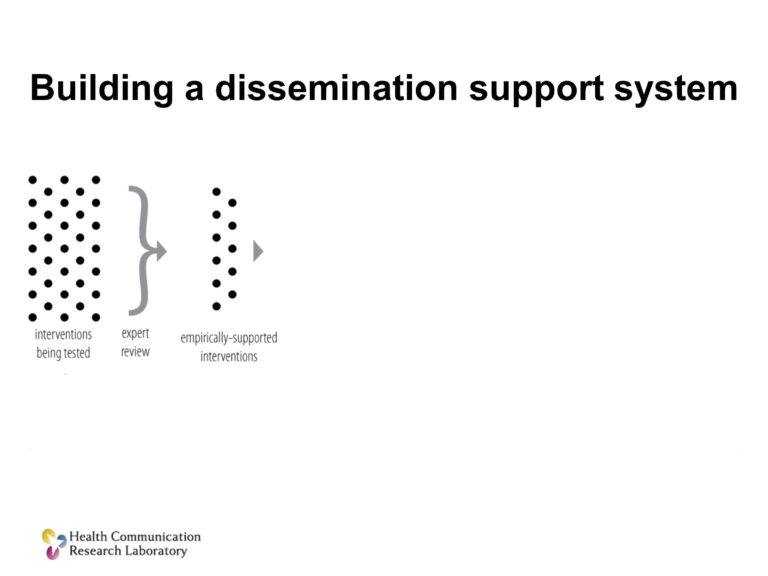

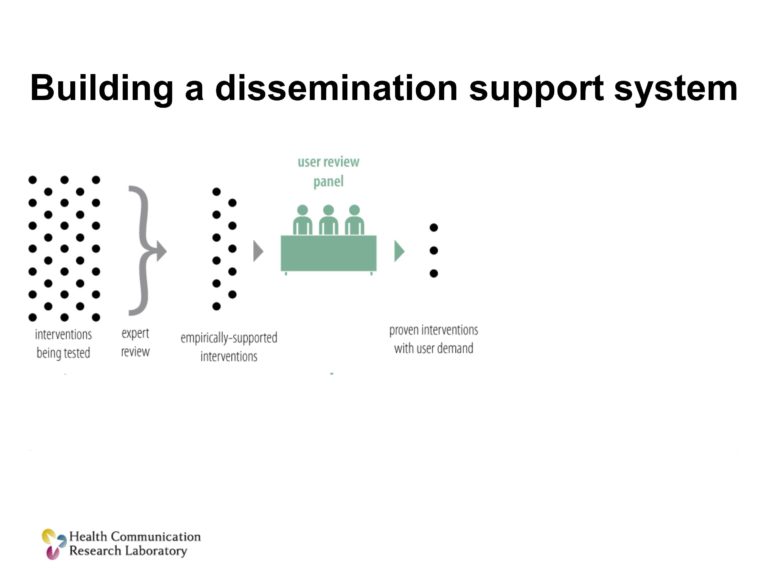

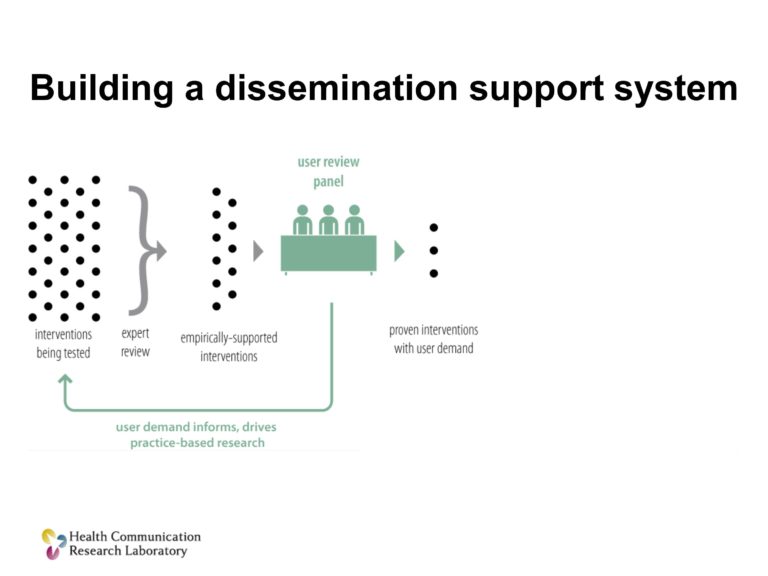

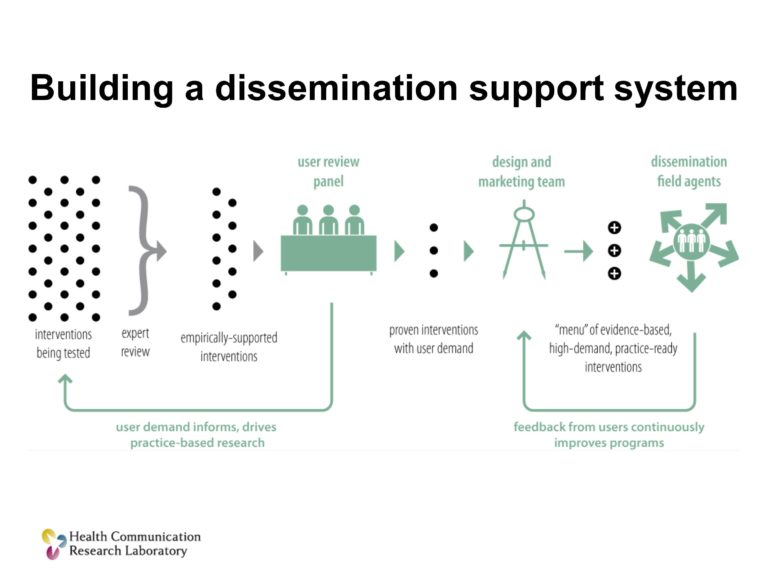

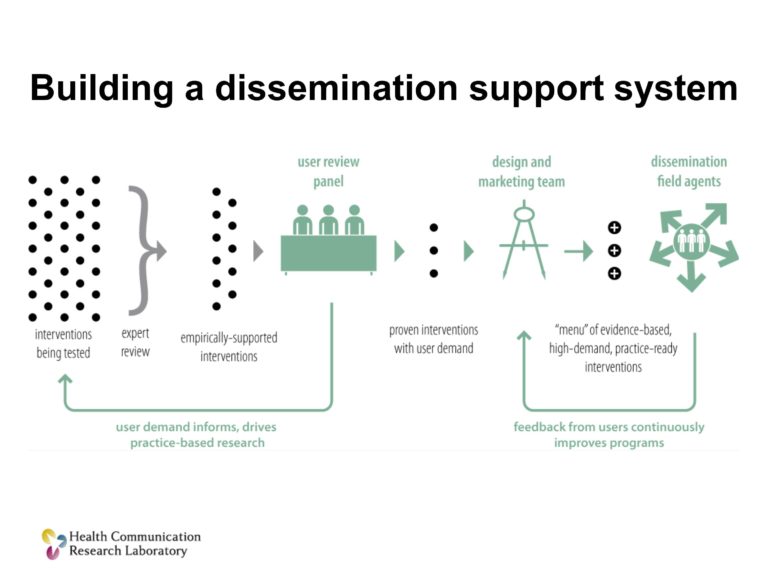

The dots that you see here on the left, these are solutions that we might be testing.

And we take them through an expert review process and we narrow them down to some subset that are empirically reviewed. And we have great systems for doing this. Our journals do this. Our scientific peer review for grants does this. Our systematic evidence reviews do this. We’re really good at his. All of this is in place already.

What we need to do is add to this what I’ll call is a “user review panel.” Some body of practitioners and leaders who are working in service delivery and clinical care in your work who can look at this and say, “Okay, of the stuff that you have evidence for, here’s what we really could use.” And that’s going to narrow the subset a lot.

Now, there’s and important ancillary benefit of doing this, which is the decisions of that sort of a group are going to inform future research that gets developed. Once you know what people need and what they’re looking for, you can develop and test solutions that meet that.

The next thing we’re going to do is we’re going to unleash a new unit, a design and marketing team, to take those solutions, those treatments that are both proven scientifically and have user demand, and they’re going to make them better, and they’re going to make them ready to use.

What you’re going to end up with at the end of this process is a menu of evidence-based, high-demand, practice-ready solutions. And that’s going to grow. That’s going to constantly be growing.

Then what you want to do is have a cadre of people, boots on the ground if you will, I’ll call them dissemination field agents. Their job is to get that menu, get items from that menu into practice. How can I work with you, the clinician, to figure out which of these solutions is going to work for you.

Let’s help you choose what would work for you, let me help you implement it in a way that fits your particular context and settings and populations. And if you have problems, if you have questions, I’m right here. I’m right here to help you along the way.

There’s also a collateral benefit here. Those boots on the ground are going to figure out pretty quickly what’s working and what isn’t. And they’re going to feed that back into the design and marketing team for a process of constant improvement.

Three things that we can do: a systematic user review process, design and marketing teams to take scientifically tested products and make them ready for practice, and scientific field agents to help people adopt, choose, adapt and use those solutions.

Thank you.

Questions and Discussion

Question: There’s one difference that you didn’t mention between the car company and what we do, and that is that people pay for cars, so that generates the profits to support all the rest of the system. So who pays for all this?

I have a lot of practice answering this question, as you might imagine. It’s always the first question that gets asked.

I would say this. Number one, in my world, public health, particularly thinking about solutions for vulnerable populations, there are many organizations that need what we do. There are very few that have large discretionary resources to pay for it. There aren’t a lot of businesses lining up to say, “Hey, this looks like a great business model. Let’s try to sell things to organizations that are resource-poor.” So, if that’s the reality, how do you overcome that?

I think there are a couple of answers. One is that if we believe that as a society we’re going to invest in research to try to come up with answers to problems, and we get answers, then we let them sit on a shelf — that’s poor value. So, that is, in fact the role of government. When markets won’t step in to solve a problem, and you’ve got some social good that’s at stake. I think I could make an argument that there are federal agencies who, in fact, should be doing exactly what this sort of model suggests. That’s one explanation.

The other explanation is, frankly, the research community has an enormous stake in this. How long do you think billions and billions of taxpayer dollars are going to go to fund research that doesn’t improve people’s health or improve their lives? I think we’re wearing out our welcome, if you will, in that regard. What if some portion of the research enterprise didn’t just fund more research about implementation, but set up systems through which these sorts of solutions might be addressed. I think those are a couple of possible ways you could fund a system like this.

Audience Comment:

I represent sort of the end game that you’re talking about. I represent a particular framework of evidence-based kernels that have taken on a life of their own. When people ask where do we get the funding — I think partnerships. That’s where the funding would happen. There are groups within our field in communication sciences who are making the end part happen.

Clinicians are taking off — PBIS is a great example. Social Thinking is a great example. It’s used by thousands, perhaps millions of practitioners and families. So I’m here to figure out how do we help make those relationships come together between university folks and the end game folks so that we can find the evidence connection between the two. I appreciated this piece.

Matthew Kreuter:

I was going to apologize or maybe soften my statement a bit that we have a complete and total absence of this. The truth is, there are people who are working in this space, and you have to partner with them. We don’t have systems at a national level that are available for everyone, necessarily. But there are people who are working in this space. In fact I shared a ride in from the airport yesterday with one of them.

Question: Patients don’t really choose their treatments. How does it fit into your model where you have a situation where practitioners are essentially providing the knowledge about the treatments?

I think the best way to answer your question is to clarify who I see as the consumers for the sorts of treatments we’re talking about. It’s very much like the distinction in the last talk between school boards, and actual schools, and the students themselves. The students and the families, in this example, were the ultimate beneficiaries of this. As they are with the work that we do. But they’re not the consumer.

The consumer, in my view, is the organization that’s going to adopt some practice that is going to be come — it’s not going to be at the discretion or choice of the consumer, it’s going to be the agency or organization that is serving them has decided to do things in a certain way.

Question: Not only are we researchers, but many of us in this room are also teaching on a regular basis with our students, both at the undergraduate and the graduate level. Do you have some thoughts about an undergraduate curriculum? Should we be thinking about market research at the undergraduate levels?

That’s a great question. Here’s what I think. I think it would be wonderful if people in our discipline knew how to do all those things. And I think you wouldn’t get any of your core curriculum taught if you aspire to do that.

The best we can hope for is to introduce them to some ideas and concepts about some of these related fields and to take a truly transdisciplinary approach to education. Where you have them think about solving problems in the field not from their narrow, siloed, disciplinary perspective, but what do all of these other fields already know that can help you solve that problem. And in part, teach people where to look for help and how to convene teams of people who know and do different things.

Science is about knowing. This is really about engineering. This is about doing. This is how do you get solutions into practice, and it’s not a part of my training in public health.

References

Bernhardt, J. M., Mays, D. & Kreuter, M. W. (2011). Dissemination 2.0: Closing the gap between knowledge and practice with new media and marketing. Journal of Health Communication, 16(sup1), 32–44 [Article] [PubMed]

Dearing, J. W. & Kreuter, M. W. (2010). Designing for diffusion: How can we increase uptake of cancer communication innovations? Patient Education and Counseling, 81, S100–S110 [Article] [PubMed]

Kreuter, M. W. & Bernhardt, J. M. (2009). Reframing the dissemination challenge: A marketing and distribution perspective. American Journal of Public Health, 99(12), 2123 [Article] [PubMed]

Kreuter, M. W., Casey, C. M. & Bernhardt, J. M. (2012). Enhancing dissemination through marketing and distribution systems: A vision for public health. In Brownson, R. C.,

Colditz, G. A. & Proctor, E. K. (Eds.), Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice (pp. 213–225). New York: Oxford University Press.

Kreuter, M. W. & Hovmand, P. (2013). Training Institute for Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health. Available at http://conferences.thehillgroup.com/OBSSRinstitutes/TIDIRH2013/agenda.html