The anatomy of the implementation of a universal newborn screening program in Colorado and across states

The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity. Additional presentation slides can be downloaded by clicking the PDF button in the toolbar.

I wish I could start out with efficacy data, which we have none of. I wish I could start out with a standard research treatment model, which is random assignment to treatment, which we have none of. But this is the story about the implementation of universal newborn hearing screening. And it didn’t do anything in the way that it was supposed to.

The national public health goal was to institute universal newborn hearing screening across the United States. We have about 4 million babies born every year in the United States.

Unfortunately, at the time the NIH set this goal, we didn’t have efficacy data. Today, I’m going to show you some data, and you’ll have to make your own decision on whether you think it actually answers the question of “should we have done this, does it make a difference?”

The Colorado Home Intervention Program

We had had an office of demonstration grant: we had started our parent home intervention for deaf and hard of hearing children in 1970. We had 10 families. They were brought into Denver, they stayed in a little house trailer. After the federal grant was over in 1975, the Colorado Department of Public Health decided to fund the program, but it was only for people who were rural and mountain families, and only for Medicaid or very, very low income families.

We had decided that we wanted a program that was equitable across the state in every community. We decided that in order to do that, we had to have a provider who was skilled who was an hour commute from every home in the state of Colorado. We stuck up this map of the state of Colorado, and we put pins in the map where we knew we had qualified people. Then the rest of the map was completely blank. And we set out, community by community to go into the communities to ask them to help us identify someone who was willing to be trained.

We had no money to pay them, because this was pre-Part C. We talked the state department into giving us training money. We identified 150 providers from around the state in every community. And we started training them. Four times a year they came to Denver. We couldn’t pay them for training, we paid their transportation — most of them it was just gas money to drive in. And they waited until we identified a baby who was birth-to-three who was hard of hearing. But years could go by — sometimes six, seven years could go by before they got anybody.

Basically, by the time universal newborn hearing screening started in 1992, we had had a state-wide early intervention program since the early 1970s. Over time we had gotten funding for the program straight from the state legislature. It was a line item in the state budget. We had to appear every year at the state legislature to justify its existence, and they were always wanting to kick it out of the budget.

Because we had to do that, we established a state-wide assessment protocol because we needed to present data every year to say it was worth their spending money for us to have this home intervention program.

That was a humbling experience because we started with all of the standardized tests, which we had to actually send assessments all over the state on buses and things like that, and train people. So, we ended up with a whole series of parent questionnaires, many of them were from research studies that had been done on other populations.

It turned out the program became so successful that middle income families in the urban area actually protested in the department of health, and threatened to go to the legislature because they couldn’t have access to the program. This is the first time we’ve have a social program that people begged to have.

The public health department agreed to give access to our trained people, but they had no funding. So in order to do this — this was again pre Part C — the families were connected with the provider and they arranged some way of getting paid. Either the family could pay for it, which in most cases didn’t happen. The school district sometimes would pay for it, developmental disabilities would sometimes pay for something. In some cases where they had no money at all, they worked out a barter system, so we’ve had everything from babysitting exchange to haircuts to fixing automobiles to a family on the reservation slaughtering their sheep every once in a while to give meat to the provider.

While this was going on, universal newborn hearing screening was started at two hospitals in the state, and it started to change everything.

Again, we had no money to start this program, so when universal newborn hearing screening began, we had some pretty crazy ways of implementing services. We once had a small community that talked their local McDonalds into donating 100% of their french fry sales so they could by screening equipment for the hospital. Our first two hospitals used volunteers. We got money for the equipment donated. We used retired people who were volunteers, and we started screening.

In our early intervention program, we did have a trainer-of-trainers model. We had regional trainers that we would train them, and they would go out and train the other 150 providers.

We instituted, after universal newborn hearing screening, deaf and hard of hearing sign language instructors who were available to all families if they wanted them.

We had the emergence of the Colorado Families for Hands and Voices, which was a partnership with families. They started a leadership training program, whey have 1,500 people in the state, people with Deaf and hard of hearing kids, so it’s almost like 90% of all families with Deaf or hard of hearing children, on their registry. And we had money to provide 1.5 hours of intervention in the home with a trained early intervention provider.

In those days we were spending about $2500 per year for a child. When universal newborn hearing screening started, we had 60 children. In 1994 I got an NIH grant to look at the predictors of successful outcomes for deaf and hard of hearing children.

Anatomy of a Universal Newborn Screening Program

After I got the grant from NIH, I actually got a call from NIH from the program officer asking us is we could run our data to see if we could show that identifying children early made a difference. Because they wanted to push universal newborn hearing screening and we were the only ones they thought might have some data to do that.

The problem was, we weren’t smart enough when we did our proposal to NIH — and neither were the reviewers — so we weren’t collecting age of identification. So we had to go back and take all of our kids and go back to the hospitals and find out when the kids were identified. And it was all done retrospectively because we didn’t even have the question. And I’ll show you what those results are.

So we’re doing this study, everything is changing in the state. NIH, everyone in the country is wanting to start universal newborn hearing screening — we ended up getting a grant from maternal and child health to teach states how to do a system to implement universal newborn hearing screening because we had started and done it fairly successfully in Colorado.

Series of Questions

I met with the chair of the Colorado State Genetic/Metabolic Screen Committee because they were the only ones in the state who had universal screening — it’s the PKU screen. We went to lunch with her, and I wish I had saved this napkin because she started giving us directions on what we’re supposed to do, and we started madly writing this down at lunchtime on all the steps of all the questions we had to answer to get universal newborn hearing screening legislated in the state.

These were the things she told us we had to do:

- We had to show the frequency of the disorder merited screening.

- That we could detect it accurately in mass screening.

- That we had an acceptable ratio of false positive screening.

- That the screening programs didn’t cause parental harm.

- That there was effective treatment available and assured.

- That early intervention improves outcomes.

- And that costs were reasonable and justified.

At the time, we didn’t actually have data for any of these. But this was what they said we were going to be asked by everybody who was involved with universal screening, and if we couldn’t answer these questions, we weren’t going to get it.

They basically told us, we didn’t have a snowball’s chance. We were not going to get universal newborn hearing screening legislated.

We also met then with the Academy of Pediatrics, the most powerful lobby for us. And the most powerful committee within the Academy of Pediatrics was the Fetus and Newborn committee. One of their people in Rhode Island, Dr. Betty Vohr, arranged to have a meeting. We were asking them, what do we need to prove to you to get the pediatricians to support universal newborn hearing screening? They said, and I almost fell out of my chair when they said, “You have to demonstrate that the impact of deafness is as serious as PKU, and that the intervention is successful.” That was a show stopper.

Then we went to the national genetic/metabolic and they said, “In addition, you have to prove to us that you do not cause social/emotional harm like cystic fibrosis.”

You die from cystic fibrosis. And at the time, what happened was their false positive was so high that even after they told parents the child didn’t have cystic fibrosis, the distress that remained for those families was so damaging that their relationship with their children was really impacted for a lifespan because they were waiting for the shoe to drop and for somebody to tell them that actually, no, they really did have cystic fibrosis and they were going to die from it.

We had to convince the audiologists, because our audiologists also thought that even if we knew the child was deaf, we should never tell the parents because we were going to ruin the bonding. So even within our own profession we had a lot of naysayers.

We had to have evidence that the diagnosis had to occur as close to the newborn period as possible in order for optimal outcomes to happen. Because otherwise, if you can do it later, why do you need universal newborn hearing screening. You have to prove that it has to be done immediately.

The Data

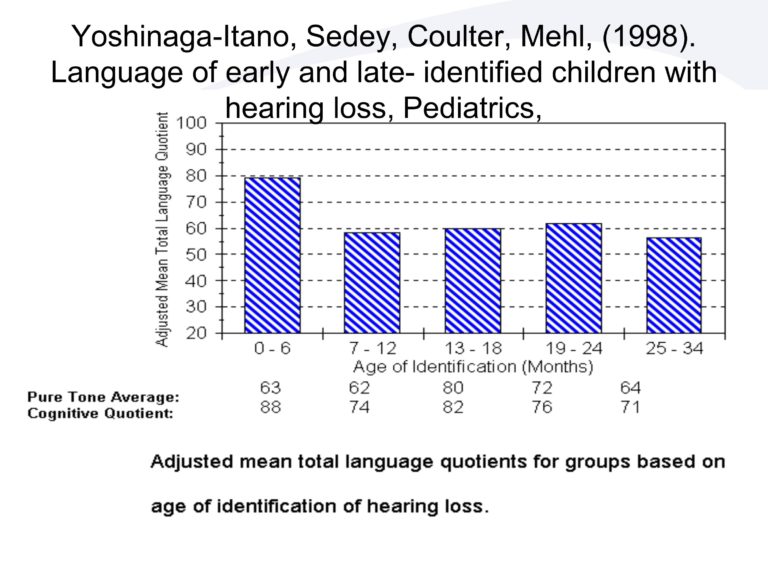

So here’s what happened with the longitudinal data that we had. We did the study we were asked to do, and we came out with this. The first bar is the children identified in the first six months of life. And you can see, if I had done this in a pure way, we would have kicked out all the kids who were multiply disabled. I had some kids with a cognitive level developmental quotient of 20 in here, because we took the whole population of the state.

The only reason I did that, is because 40 percent of the kids are multiply disabled. If I take out all the multiply disabled kids, I don’t have any kids left in any of the categories.

So, we took everybody. Initially, I thought the instrument is not sensitive enough to show any difference. So we should just go before 18 months, after 18 months, because I didn’t think I could ever show anything for birth through 8 months.

My statistician, who knows nothing about deafness really, came to me one day, because we were designing this retrospectively. She said, “You know, amazingly enough, we have equal groups in each of the age of identification groups by six months of age, and I think we should do the research to look at each of those age of identification groups.” And I told her not to do it, because I was sure we weren’t going to get the effect. Fortunately for me, she didn’t listen to me at all. She did these results, and she comes and she says, “You have to look at this, this is absolutely amazing.”

I didn’t believe it when we first did it, so we checked the data, every data point like three time with three different people to make sure it was accurate. Because what you’re seeing here — this is developmental quotients. So this is developmental age, language age over chronological age. If you’re early identified, even with all the multiply disabled, cognitively impaired kids, the average of the group is an 80 developmental quotient which is right at the borderline of normal.

If you’re identified between any of those other age of identification groups, you were at 60% of chronological age. And, there was no difference. It didn’t incrementally improve if we identified you at 19-24 months or 7-12 months. It wasn’t linear at all, it was really a skewed distribution.

It turned out we didn’t even need statistics for it. Without even knowing the question, if I just gave you a whole stack of our results and I said divide these into two groups, you would have done it. Because there was almost no overlap between the birth through 6 and the other kids. They were so different from each other.

That is the part of the data the Academy of Pediatrics looked at, and they said, that shows us we have to do it early.

This was just descriptive. There was nothing causal about it. The difference is, I had data, population data of the whole population in Colorado before universal newborn hearing screening ever started. Then I had population data of the state after universal newborn hearing screening started.

So instead of a random assignment to treatment, the entire state was the treatment. First the state was a control, then the state was the treatment.

It turned out that we had to identify really early, or we weren’t going to get the same results. And the early intervention providers were blinded to the results so they didn’t know — we didn’t even know — that age of identification was important. They were all the same providers. They had the late-identified kids and the early-identified kids. They were doing exactly the same thing.

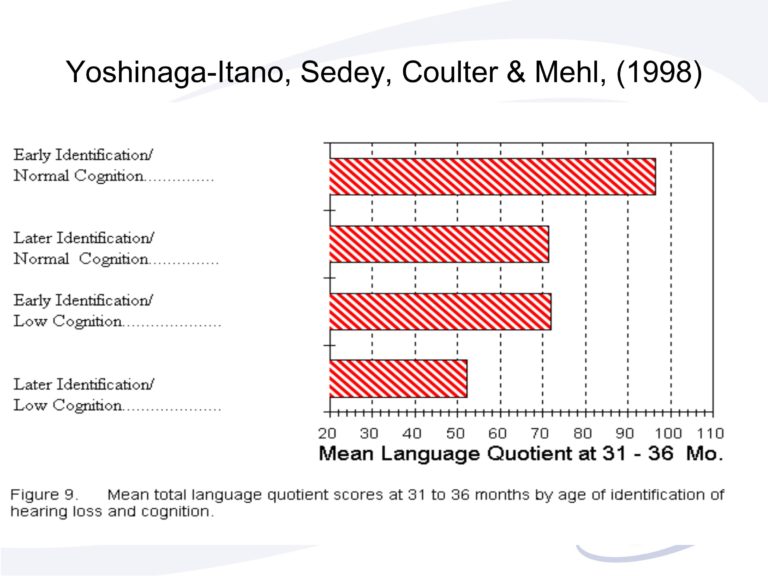

This actually is the graph that convinced the Academy of Pediatrics to support universal newborn hearing screening. Remember, they told me unless you show that not identifying is as bad as PKU, and that you have a treatment that will take away that negative impact, we won’t support it.

This is what they looked at. The first bar, early identified kids with normal cognition — they were over 90 developmental quotient.

The next bar are late identified kids with normal cognition. This was the bar that just shocked them. It shocked us too.

The third bar are early identified kids who were cognitively impaired. You can see the distributions and the means were identical to the late-identified with normal cognition.

They interpreted our results as, if you don’t identify hearing loss in the infant period, you create an environmentally caused cognitive disability. And so they basically said, this is the same as PKU to us.

And this last group, unfortunately, are the late-identified kids who are multiply disabled with low cognition.

So it turns out that when we did this study, we only got two variables that predicted outcome: cognitive level and age of identification.

The age of identification effect was there for every degree of hearing loss, for all socio-economic levels, for all cognitive levels, for all methods of communication, for both genders and for all ages. It didn’t matter when we did it, it didn’t matter what the other variables were, we got the effect across the entire population.

Marketing Campaign

We had all kinds of campaigns for all kinds of different audiences. Our biggest audience was actually not parents who were going to have identified children, it was parents who were going to have normal hearing children. And basically, we did parent magazines, we did interviews all over TV, radio, to pregnant mothers saying ask your doctor if your baby will be screened for hearing before hospital discharge. You want to know before you leave the hospital that your baby can hear you say, “I love you.”

Basically, that was one of the most powerful messages for the universal hearing screening. It appeared on milk cartons. Parents were reading the parent magazine they were going into their obstetricians asking whether there was a screening program for them.

Screening versus Intervention

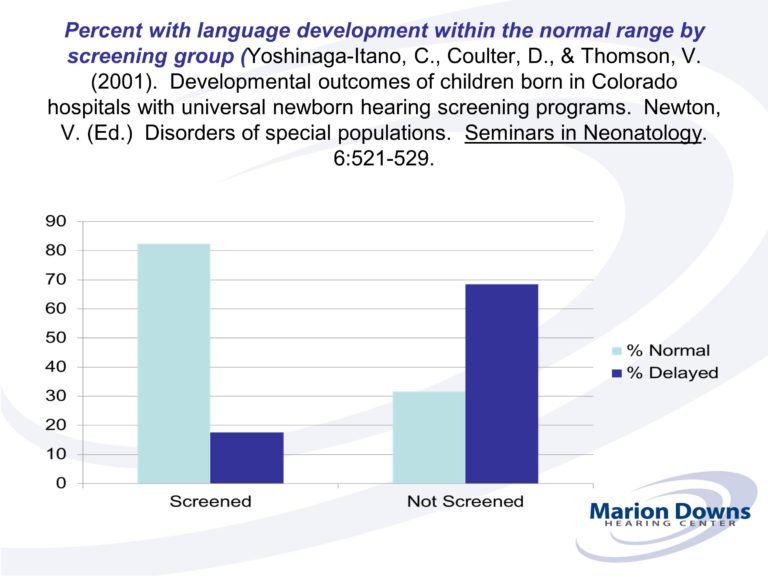

Then the physicians said, okay, but that’s just age of identification. If you’re born in a hospital are you going to have the same results? Because they wanted to bypass the intervention.

Here’s the problem: If you were born at a hospital in Colorado that screens, you had an 80% probability of being at age level from birth through five years of age. If you were born at a hospital that didn’t screen, you had a 30% probability of our whole population.

But, do I believe that screening, by itself, causes kids to be at age level? Absolutely not. Screening opens the door to identification. Identification opens the door to our appropriate high-quality intervention program. But, of course, people didn’t listen to that part. This is part of the problem. Twenty years later, people are now listening.

Screening programs make a difference, but not without high-quality early intervention programs. I can show you that is true, because since we published our results in 1998, there has been no other study published in the United States to show the early identification effect. The reason for that is because they all looked at just the screening and identification. The early intervention characteristics were random. They just picked kids from all over, they had no control over the early intervention delivery fidelity or delivery of service, and so basically they got no results. If you don’t have quality intervention, there’s no difference between if you early screen and you early identify — your kids are going to be two standard deviations below the mean.

If you do early-identify, and you have a high quality program, you’re likely to have 80% of the population with normal cognition at age level.

This was like a racing train. In the four years that we had the maternal child health grant from 1996, we went from 2 states to 26 states with initiatives to establish universal newborn hearing screening. We got every constituency on board to support universal newborn hearing screening. But here’s the thing: We used such a non-traditional research design to do it that actually, we ended up losing our NIH funding and losing our MCH funding at the end of that period of time. Because the reviewers just couldn’t accept that an epidemiological population study was the best way to go, and everybody thought they knew how to do it better. Even though we had been working on this for like 20 years.

Unfortunately, because of that, I think because they didn’t focus on intervention which was, to us, the most important, we’ve never been able to show the effects besides the Colorado program. But I think now I’m going to be able to publish some of that.

UNHS Across States

One of the reasons we has this runaway train was because MCH and CDC put money into the programs to help states establish it. In 1999, we passed legislation federally to get money to states, so that allowed other states to develop their universal newborn hearing screening program.

Unfortunately for Colorado, we had already done it with no funding, so we didn’t get any funding. We were the only state that got no funding for equipment, no funding for infrastructure. We did get funding for data management. Fortunately for me, CDC really liked the designs and so I was able to keep funding over time.

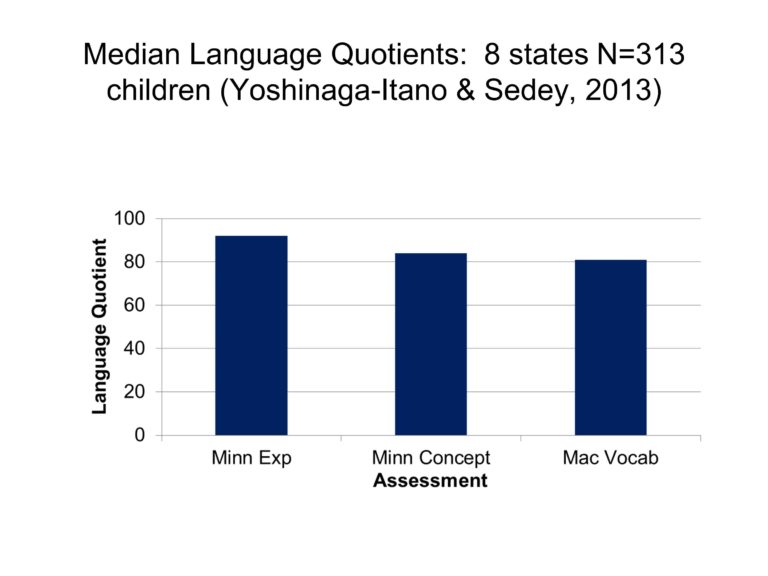

We now have, I think I have 15 states on board to collect population data on their entire population.

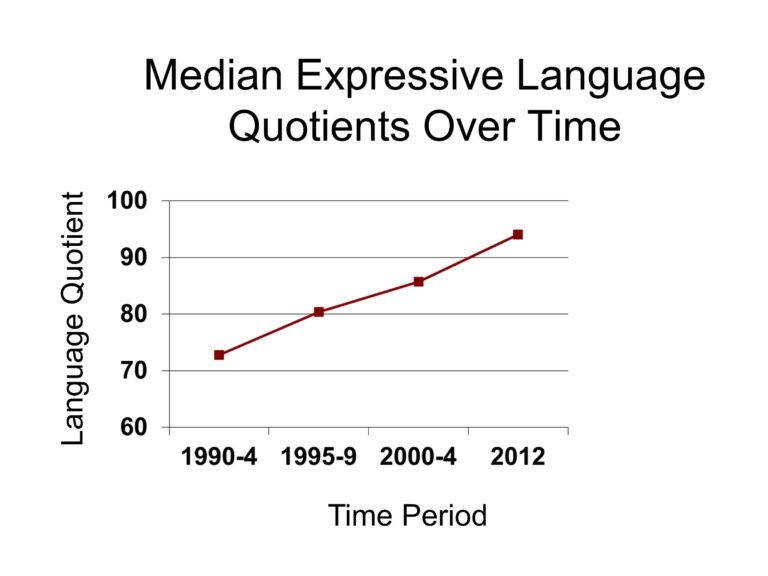

This we did last year, but we now have a thousand assessments that we’re looking at nationwide. And we’re showing the median language quotients across all of these states are within the normal range.

So I think we are now going to be able to publish some data in the United States that says, if you have quality intervention, you are going to be able to show that early identification and early intervention makes a difference.

Now, states differ in their outcomes. Here’s seven states, and you can see that if you look at the outcomes of their entire populations, state 7 is not doing so well.

I can tell you that now we’re beginning to compare the characteristics of the states, there are some things state 1 has that state 7 doesn’t have. The question is, if we can get state 7 to implement some of the things states 1 and 2 have and they are doing really well, will we be able to bump up the population’s statistics so they are now doing as well as states 1 and 2.

We’re now doing all of these comparisons. The results look very similar regardless of what instrument we use. This is the MacArthur, the last was the child development inventory. As you can see, state 3, for instance has a language quotient of 70 which is in the impaired range, not within the normal range.

We also know, at least within the state of Colorado, you maintain development within the normal range to age seven.

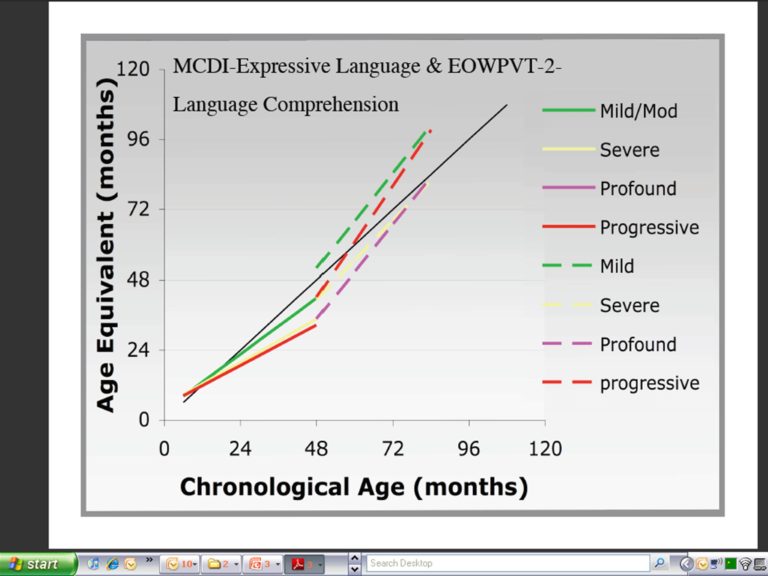

Here’s our results with one of our instruments, the Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test, and you can see by age 7 the black line is normal development. Every group, mild through profound, is at age level, it’s the same distribution as the normal distribution on the Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test. I can predict 70% of the variance in the outcome on every single language measure we do within 7 years of age. And that is pretty amazing to be able to predict at that level.

Economically and Linguistically Diverse Families

We finally, after years of doing this, have something we can teach parents. Because everything else we’ve used that predicts outcomes was cognitive level — we can’t teach that — degree of hearing loss — they come with a degree of hearing loss — age of identification — the health system determines that. So one of the criticisms of our data is we never had a maternal level of education effect. Everyone said that’s impossible because maternal level of education predicts all language outcomes in every population, everywhere. There must be something wrong with your data because why don’t you have this effect.

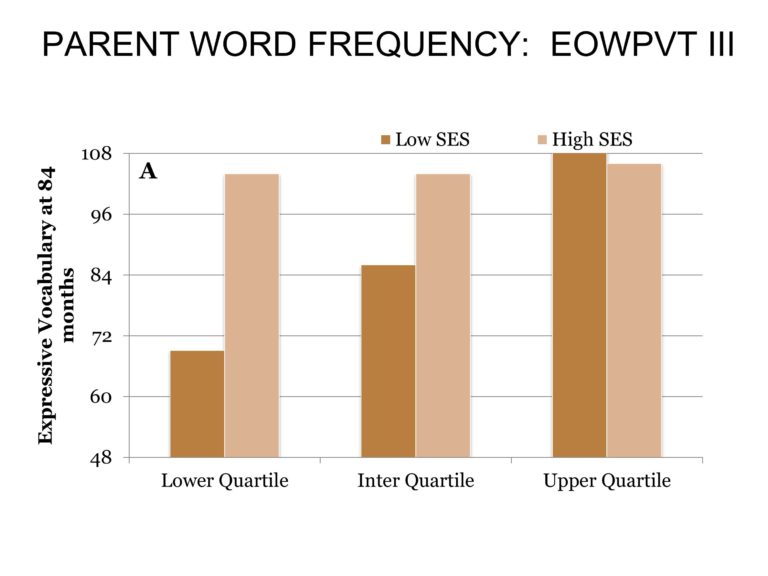

I can show you now why we don’t have this effect. After thousands of video tapes and 13 hours of coding on each of the video tapes, we’ve divided the parents on parent word frequency. The lowest quartile are 984 words in a half-hour video tape. Middle quartile is 2,145 words. Upper quartile is 1,550.

This is by SES, and this is why we don’t have this difference. The dark bars are low SES, and the light bars are high SES.

If you have high SES, and you’re in the upper quartile of talking, you talk a lot, the expressive one-word vocabulary test score for you is above age level at 84 months. Interestingly enough, even if you don’t talk very much, if you have low maternal education and you talk a lot, your child has exactly the same vocabulary score as high income.

This is the sad thing about low talking and low income — if you have low talking and you are low income, look at the difference in your vocabulary score at 84 months. It’s humongous.

There are some other things, but this is the graph that we show — it’s like a scale. If you’re early identified and you have high talking and high cognitive ability and you have better hearing, you have the highest scores and the highest developmental trajectory.

Every time we put something on the scale to say, you’re IQ is impaired or borderline, or maternal level of education is lower, your hearing loss is of a greater degree, it drops the trajectory. Over the 7-year period, we know what percent it decreases the development over time with each of the variables that we’ve been measuring.

We do know that high-quality early intervention programs do have a positive impact on language outcomes. Even though I can’t tell you all of the features of the fidelity of intervention, in our early intervention program we are teaching parents to talk more to their children, and that’s having a tremendous impact. It’s not just talking more, the quality also improves with talking more, but it’s the easiest thing to measure.

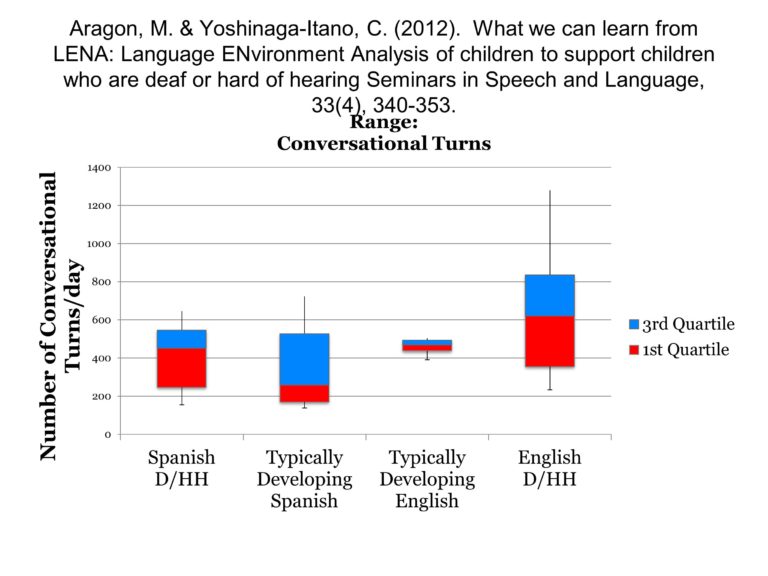

We also know that we’re effective with Spanish-speaking families. This is a graph that’s being used for Head Start programs. We use the LENA with this. The amount of talking within Spanish-speaking deaf and hard of hearing kids in our intervention is equal to the English speaking kids who have much higher incomes and higher socio-economics. But the difference between hard of hearing English speaking with intervention and the typically developing English speaking compared to the Spanish hard of hearing with the Spanish typically developing is actually the same ratio. Which says that with intervention we’re making that much of a difference in how effective parents are at talking with their kids.

We have other data that talks in terms of money. Everybody wants to know about money. State residential schools for the deaf have lost enrollment, many of them have closed. Center-based programs in the United States are much, much smaller than they’ve ever been because the kids are going into the mainstream and they are functioning at the levels of their typically developing peers.

This is just to show you that over time, with assessment, from 1990 to 2012, this is the increase on the developmental quotient on the same instrument over time in the population to show how universal newborn hearing screening and quality of early intervention makes a difference.

What Has Happened Since UNHS

What has happened in the field since universal newborn hearing screening? ABR was in research for 20 years before we started universal newborn hearing screening. Nobody did it clinically. Once we started universal newborn hearing screening, the only way you can identify hearing loss is by identifying physiological measures. So ABR started being used, ASSR started being used. Otoacoustic emissions was not in the field — that started being used. High frequency tympanometry was in the research, was not being used — we now use that regularly. We now have a diagnostic protocol for auditory neuropathy. We now are implanting kids at 12 months or younger. We’re doing lots of things we’ve never done before.

But universal newborn hearing screening is one of those things that’s really a weird thing — it was like a racing train where we’re hanging on just to hold on because it happened overnight in the United States, and it’s doing the same thing across the world.

References

Yoshinaga-Itano, C., Sedey, A. L., Coulter, D. K. & Mehl, A. L. (1998). Language of early-and later-identified children with hearing loss. Pediatrics, 102(5), 1161–1171 [Article] [PubMed]

Yoshinaga-Itano, C., Coulter, D. & Thomson, V. (2001). Developmental outcomes of children with hearing loss born in Colorado hospitals with and without universal newborn hearing screening programs. Seminars in Neonatology, 6(6), 521–529 [Article] [PubMed]

Yoshinaga-Itano, C., Baca, R. L. & Sedey, A. L. (2010). Describing the trajectory of language development in the presence of severe to profound hearing loss: A closer look at children with cochlear implants versus hearing aids. Otology & Neurotology, 31(8), 1268 [Article]

Aragon, M. & Yoshinaga-Itano, C. (2010). What we can learn from LENA: Language ENvironment Analysis of children to support children who are deaf or hard of hearing. Seminars in Speech and Language, 33(4), 340–353 [Article]