Lessons learned from efforts to scale up School-wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS)

The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

I’ve been asked to talk about this notion of how you take things to scale. We heard this morning about kernels. We heard about programs. We heard about implementation science. I’m going to do a presentation that is a little less about implementation science, and a little more about implementation muddling along, if you would. The major theme: in the half hour that I’ve got, I’d like to present five major lessons learned. Things that I would encourage you all to think about as you’re taking brilliant ideas, elegant programs, sophisticated strategies, and putting them in place.

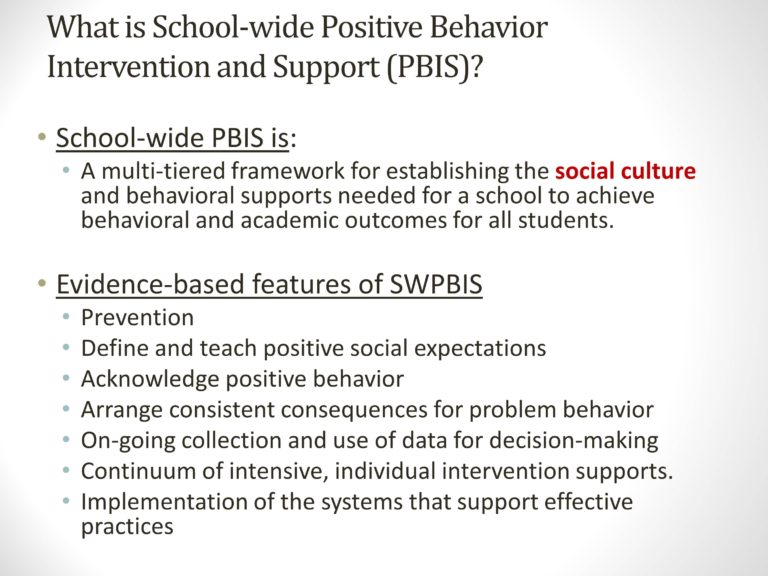

What is School-wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS)?

School-wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports

The program or the approach that I want to talk about is something that’s called Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports. Essentially, it’s this: I want you to think about schools, and I want you to think about how to make schools more effective learning environments. The whole school. I want you to think not just about what you know about individual children or classrooms, which is what we typically have done.

One of the messages that we would bring is: you will never get the technology that you know about helping individual children, individual families, and individual classrooms, to be implemented with fidelity and sustainability if you don’t use the whole school as the unit of analyses. So make the school an effective learning environment.

To do that well, you can condense the last 40 years of school-based behavioral research into four major messages.

Four Major Messages of School-based Behavioral Research

- Make a school highly predictable. Make the environment one in which everybody is clearly aware of what the expectations are.

- Make it consistent across people, place, and time. Make it so that everybody knows the same messages.

- Make it extraordinarily positive. Rather than focusing on what not to do, focus on what to do.

- Make it safe. Make it safe both physically and make it safe in terms of how the child feels. So for issues related to trauma-induced problems, you’ve got to have an environment that is welcoming and really works.

So part of what we’re looking for is a framework, and George’s big message – George Sugai, who is the person who really came up with most of this – his big message was to focus on the whole school and recognize that students learn as much or more from each other than they do from us, especially when it comes across in terms of the social interaction patterns. If you want to change self-regulation, if you want to change social interaction patterns, you will not do it teaching one kid at a time. You need to teach groups of kids who operate with similar organizational structures.

So what we’re interested in is backing up and saying, if you want to change the whole school, what are the evidence-based practices that we’ve learned? What are pieces that actually fit?

Well, one of the first things would be focus on prevention rather than remediation. Focus on strategies where you can identify what the most common issues are and prevent them from happening.

Then this whole notion of creating something that’s predictable. Define in a school three to five positively-stated behavioral expectations. If you want to create an environment that is extraordinarily predictable, you cannot have 75 rules. Right?

You do not define all the things you don’t want. No hitting, kicking, spitting, biting, throwing, raping, pillaging. Basically, anyone who believes they can come up with a list of what not to do in a middle school is kidding themselves. So focus on three to five positively stated events.

So what do you want?

- You want kids to be respectful of each other.

- You want them to be responsible for themselves.

- You want people to behave with kindness.

- You want them to try.

There’s not that many. And you’re going to come up with them in different ways.

Teach those. Teach it very, very clearly. Teach them as behavioral concepts, just the way you teach math, reading, and writing.Never teach something that you don’t acknowledge on a regular basis. Never teach something unless error patterns are actually corrected on a regular basis. And never build something like that unless you have the data systems that will allow you to know, one, if you’ve done what you said you would do, and, two, if it’s working. Those are the basic things that we learned.

Four Messages from George Sugai

What George Sugai did in the mid-80s is he gave us four big messages.

- Social culture really matters in terms of the effectiveness of schools as learning environments. You can use a great curriculum, but unless you establish a coherent positive social culture, you will not get the effects that you’re looking for.

- Rather than trying to fix one problem after another, start by building a whole school environment that’s going to operate.

- This one is really at the heart of what I want to talk about in terms of implementation: never plan to implement effective practices unless you put in place the systems that are necessary for high fidelity and sustainability. Practices are always the things we love talking about. How do you get people to get the /th/ sound? What do you do if somebody uses the f-word? People love that stuff. But the stuff that’s not sexy is the stuff that produces sustainability and high fidelity: To what extent do you actually have the organizational structures? Do you have the policies? Do you have the staffing patterns? Have you talked about the funding mechanisms? Those things are not by themselves going to get something in place, but they are critical to fidelity and sustainability.

- The last part is something I’m going to really come back to. When you build practices from now on: no more practices with one level of intensity. If you build practices, make them work for large groups of people. If you want something to scale up, plan: For those people for whom it doesn’t work, how do you change and modify the intensity and structure? For those people for whom it doesn’t work, how do you go up even further?

Making PBIS Work

The PBIS Triangle

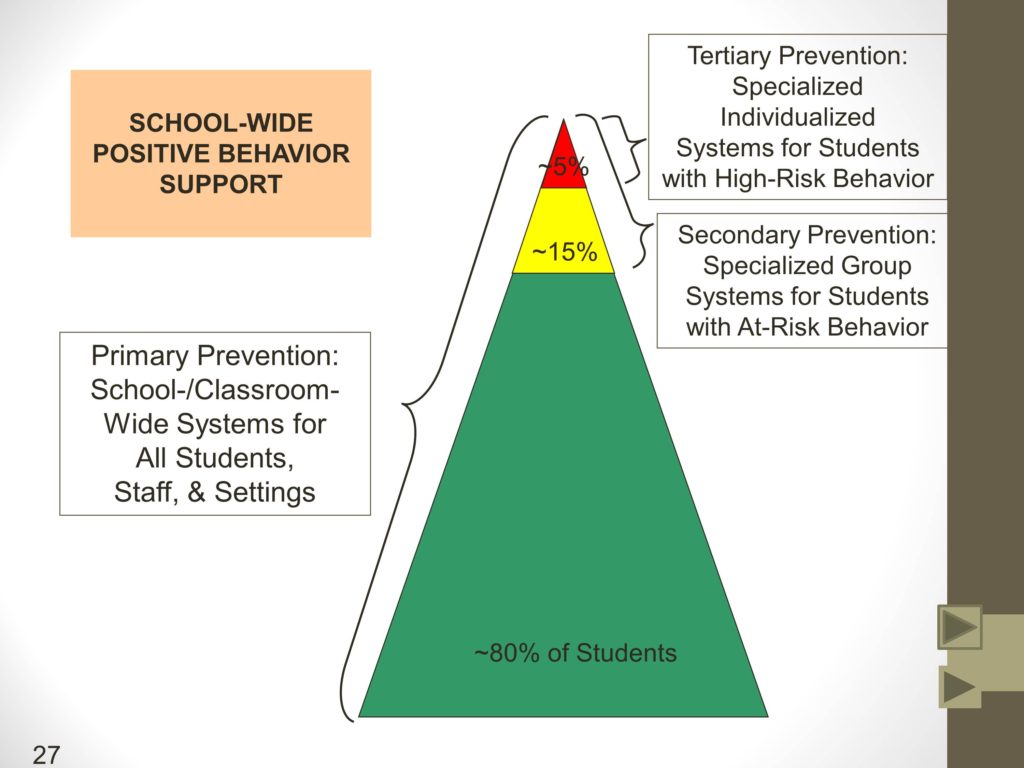

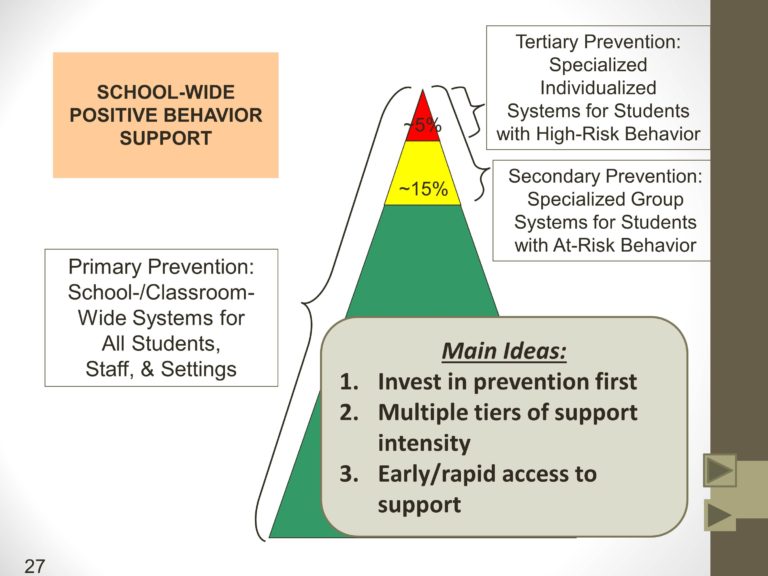

So one of the mantras within PBIS is that you have this triangle. The triangle fits with those of you who are interested in response to intervention or multi-tiered systems or systems of care structures. It’s borrowed from the community health literature. So for those of you from the health environment, this is your idea cast onto education.

The basic idea is always start with prevention. Look first at primary prevention. Implement an effective intervention, whether it be reading, math, writing, behavior, communication, whatever it is, it should be something that is extraordinarily efficient and effective that will work successfully with at least 80 percent of your population.

Focus first on prevention. In terms of behavior, this is a giant message, because one of the things that you’ve seen – if you’ve worked at all in schools – is that everybody shows up and we expect the kids to behave well. We wait for them to foul up, and then we hammer them. Right? Focus on prevention first. Build that foundation.

In the old days we would come up with these programs and we’d manualize them. We’d put them out there and we expected everyone to turn to page 9 and we would say on page 9, this is what you do. It worked great – for about 30 percent of the situations. What we left people with is this: What do you do when Elliot doesn’t do it right?

And here is what I really want you to take away: Scaling up means focusing on all.

It means focusing on high-quality education with equity for all. For kids who have difficulty learning. For kids from different cultures. For kids who don’t speak the same language. For kids who come from environments that break your heart. If you’re going to build strategies that actually work for America’s education system, you’ve got to build strategies that are going to have large-scale application.

Don’t give us something that only works for a few people. Tell me how it works for everybody, but then tell me how I get it to work for the 15 percent who – they don’t need bazooka-level interventions, but they need a little more structure. They need a little more frequency.

For example, with literacy. The green part of the triangle is a phonics-based program with explicit instruction for 90 minutes a day, for a minimum of four days a week with universal screening, progress monitoring, and effective early intervention. That’s the green. The yellow part for literacy is an increase of about half hour a day, decrease in the size of the group, increase in the frequency with which you get feedback. We can do this. Now we actually have tertiary systems. We can do that with behavior. We can do it with math. We can do it with reading. We can do it with communication, too, but we need your help.

Then, there will always be three to five percent of kids whose primary mission in life is to help us maintain our humility. Those are the kids who are actually going to teach us best.

One of the things that I’ve learned is good teachers really learn when they pay attention to the kids. Kids who have difficulty learning are the best instructors of high quality teaching. One of the banes in education are really smart kids who will learn almost any way you teach them, and then you take advantage of it even though you teach poorly. Everybody learns when you teach well.

The PBIS Triangle: Lessons

So part of what George taught us is to invest in prevention first – the green part of the triangle. Invest in doing that well. Use multi-tiered systems of support and rapid and early intervention. Focus on the whole school. Focus on extending that into the classroom, and focus on building it in a way that it works for individual kids who have real difficulty.

Making PBIS Work: Effective, Equitable, Efficient

In essence, here are the three things I want you to come back to. We talked about efficacy and effectiveness. You’ve got to have the data. If it doesn’t work, then let’s move on. What I’m saying here is getting it to work is necessary but insufficient. It needs to work with equity.

We are abandoning a huge proportion of children in the United States. Forty percent of kids in Oregon don’t graduate from high school in four years. That is abysmal. You want to get kids to communicate, we need to get kids so that they are college and career ready in time. We need kids who have the self-regulation skills, who have the organizational skills, and who have not just the tasks and skills that we’ve taught them, but the ability to learn things that we haven’t taught them.

The other part is, we’ve got to do it with a much greater sense of efficiency. One of the reasons why things are not adopted is we have not paid attention to — not just how much it costs and how much time it takes to adopt them — but how much it costs to actually sustain them. We’ve got to have things that are effective, that are equitable, and that are efficient. We have underestimated equity and efficiency in the things that we’ve built to date.

Research on PBIS

Experimental Research on SWPBIS

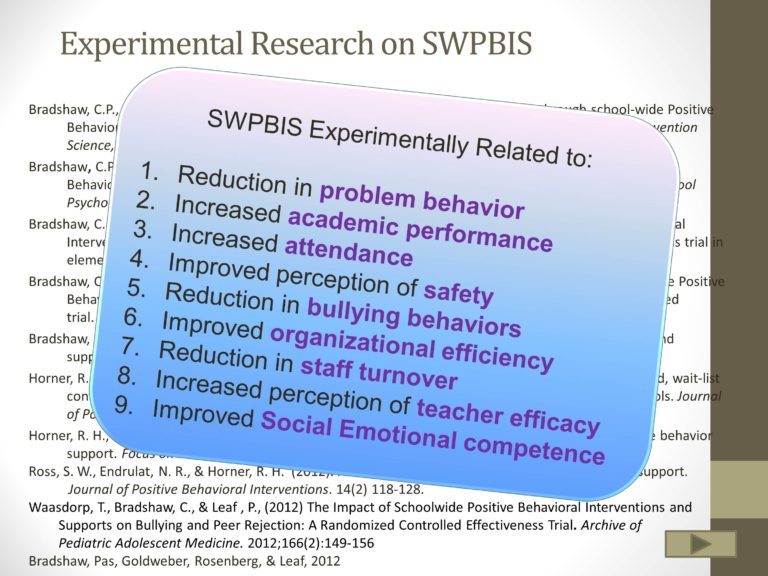

One of the things coming here, it’s required that anybody who stands up be able to actually document that what you do is functionally related to change in student outcomes. [See the References section for a list of ten randomized control trials.] I grew up as a single-case researcher. All of these studies are based on single-case methods, and all of these are group design studies. If you don’t get quite through all of them, here’s the punch line.

If you implement school-wide positive behavior support with 80 percent fidelity, here’s what you get.

- You get a 20 to 60 percent reduction in office discipline referrals.

- If you do it over three years, you get a 40 percent increase in the proportion of kids who will meet state standards on reading and math.

- You get an increase in the likelihood that kids will actually both attend school and attend class.

- You’ll get an increase in the proportion of ten-second intervals that they spend paying attention to instruction. Turns out, the more time you actually spend paying attention, the more you learn. Who’d have thought? We actually did the study to show that.

- It increases the likelihood that the kids identify the school as a safe environment.

- It decreases bullying behaviors, increases organizational efficiency, decreases staff turnover, and it increases the extent to which teachers perceive themselves as being efficient.

- The most recent study demonstrates a statistically significant effect, with a modest effect size of only about 0.3, but it is a demonstration that kids in schools implementing PBIS actually increase the social-emotional competence with which they leave.

Number of Schools Implementing SWPBIS Since 2000

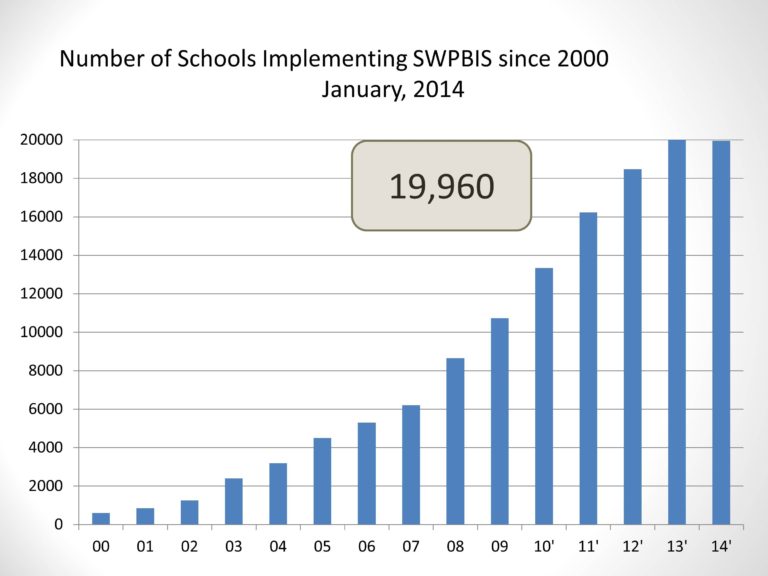

Now, we’re currently working with nearly 20,000 schools. We actually have PBIS implemented in about 20,000 schools.

School Implementation of PBIS by State

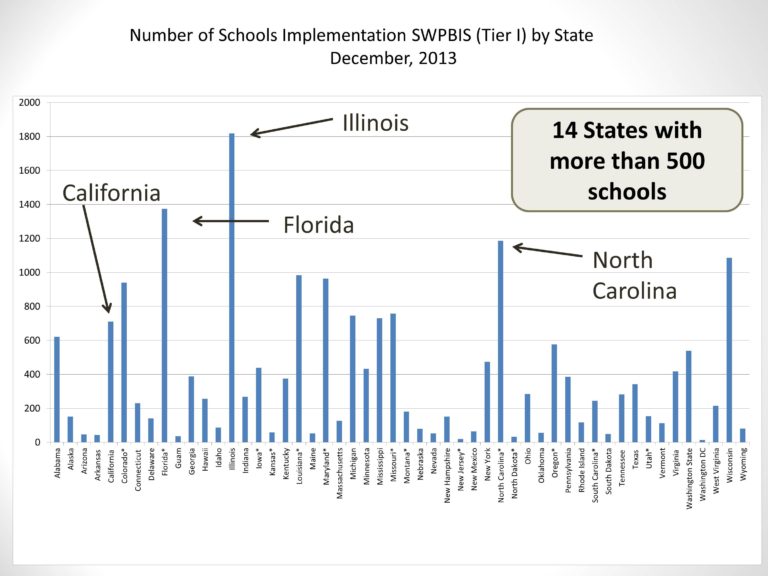

And this is by state. You can’t read this, but this is states in alphabetical order. There are over 1,800 schools in Illinois that are implementing PBIS. There are nearly 1,400 in Florida. There are about 1,200 in North Carolina. There are about 788 schools in California implementing PBIS.

Now, the thing I want you to know is there are 10,045 schools in California. So you think, boy, 744 is a lot. And then you stop and you say well, it’s really not very much.

So you say 20,000 schools. That sounds like a lot. There are 110,000 schools in the United States. Our job is to get to at least half of the schools in the United States before George Sugai retires. We need help.

Lessons Learned in Implementation

Attend to Implementation Science

So given that history, what can I tell you about what we’ve learned? First off, I would like to echo some of the messages from earlier today. We have sat at the feet of Dean Fixsen and Karen Blase. We believe that attending to implementation variables, to the drivers, the stages, the cycles, makes a difference. But part of what we’ve learned also is focus on the systems.

And in education, and I’d encourage you to look at this, be careful about the unit at which you are having an impact. Here’s what we’ve learned.

In the United States, school districts are the unit that controls education. School boards make decisions. They have funding. And for all the money the state and the Federal Government talk about, it’s trivial compared to what school districts control. You want to change schools, you must change districts. Districts are the unit of implementation, schools are the unit of analyses. The whole school, remember? Change the whole school. And children and their families are always the unit of impact.

We’ve got to hold ourselves accountable for what we’re trying to change and where we change it. So within PBIS we no longer work with individual children or schools. We only work with districts.

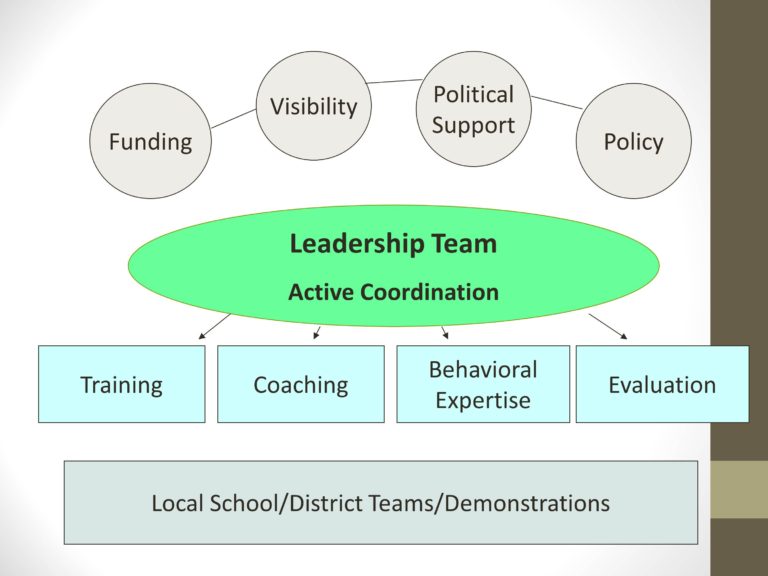

Active Coordination and the Leadership Team

When we start with a district, we want to see a leadership team. I meet with superintendents from Salinas and San Jose partly because they are looking at implementing PBIS. They have high rates of gang and child violence in their schools. They want to know: What can you do tomorrow to deal with Leonard? And we’ll say we know a lot. We can help you a lot, but we will only do that if you actually change the organizational system and produce high fidelity over a sustained period of time. Never implement something that you don’t expect to last for a minimum of a decade.

So we want a leadership team. Leadership teams always want local demonstrations. The fact that you can do it in Pennsylvania is irrelevant to people in California. The honest truth is the fact you can do it in San Francisco is unrelated to the people in San Diego. Right? So it’s got to be local.

For any leadership team, the thing they want is: Can I give you some schools, and can they be pilots or model demos? The answer always is yes. Yes. But, never implement little, tiny trials unless you build the organizational capacity for sustainability. For how long? Minimum of a decade.

So here’s the deal. You want to have a leadership team. It needs to have these features.

- Can you show me the funding that will allow you to continue focusing on this for a minimum of three years?

- Can you right now tell me how you will communicate with the community, with the families, with the businesses, with the colleagues? Everybody needs to know: what are we doing, is it working, and how is it going to work.

- Do you have the political support? One of the things we look for is if we’re going to come into the district, is the superintendent of the district going to ask how you’re doing at least twice a year? Don’t tell us to come in and help you out unless you’re actually going to build that.

- Do you actually have the policy structure set up so that if we put this in place, it’ll work? I’m going to come back to that.

Now, if the leadership team has that, here’s what we’ve learned to build. You always start with teams in the schools who do things. It’s a blast working with teams in schools. It’s embarrassing that we get paid to do that. But here’s the hard part.

Building active coordination of the leadership team.

- At the district level, always build the training capacity so that when you have done it twice, they can replicate it from then on.You need to always be training trainers.

- Never train trainers unless you train coaches. And I’m going to come back to the coaching part. It is much bigger than what we think.

- If you’re going to do behavioral support, you need behavioral expertise. Language support, math support, reading support. There’s no school in the United States right now that doesn’t have all the resources it needs to implement the green-level implementation of PBIS. No school. Every school in the United States can implement that. But to get the yellow and the red in place, you actually have to have some knowledge. And that’s where you got to build the expertise.The same is going to be true with communication. You’ve got things you can teach that everybody could do related to organizational features to build good communication systems. But to get to the kids who have more difficulty, we need to say where do you get that red level and yellow level support?

- Never do this without evaluation. Everybody here, you all are mammoth evaluators. You’ve got, collectively, we’ve got a gazillion units of data right here in this room. Here’s what I can tell you. Most of the data that we have is focused on kid outcomes. To what extent does stuttering occur? To what extent does phonemic segmentation occur? To what extent do behavioral problems occur? To what extent do health education issues occur?I want you to add this: Getting kid outcomes without measuring fidelity of implementation is ineffective. I want you to be able to say: Are we doing the intervention? as often as you say: Is it working?

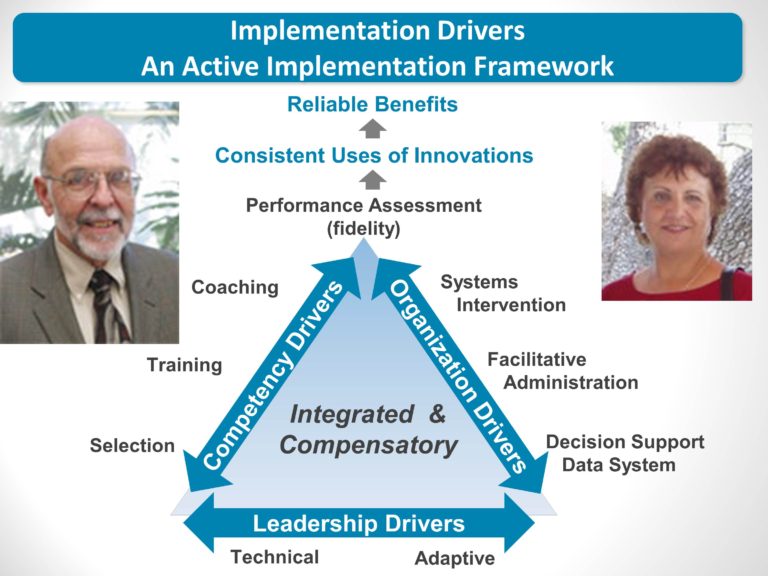

Implementation Drivers

So if we do that, that’s the system. Now, here’s the slide that Renee Boothroyd gave us. And these are the two mentors. This is Dean Fixsen and Karen Blase. Here’s what we’ve learned. I want you to really pay attention.

This is the part of the drivers that focuses on building competence, and I really want you to think about the competence you’re trying to build in regular education and special education teachers to be effective at delivering speech, language, and communication skills. Think about the extent to which you’re trying to get families to assist their children in implementation of speech, hearing, and language skills.

Here’s what we’ve learned: We love training. We love it. We do training like you would not believe. As a group, we are great. We’re actually good trainers as a field. You’re good.

Here’s what we miss.

To what extent do you really focus on teaching people how to select people who are knowledgeable and effective? So for example, one of the things I will train superintendents in tomorrow is: If you’re going to implement PBIS, I want you to build into every job description from custodian to superintendent: are you knowledgeable and skilled at implementation of multi-tiered systems of academic and behavior support. Nobody gets hired without being asked that question. Nobody gets hired without going through the interview process. How do we know if you are skilled not just at green-level strategy, but do you know how to do yellow and red? Do you know how to fit them together? Do you know, as an educator how to work with mental health, juvenile justice, and communication specialists? Do you know how to know if what you’re doing is working?

Second is, never train something unless you coach it in real time, in real place. Coaching is the process of building fluency and adaptation.

- Fluency. I learned something. Can you do it the fast way under real conditions?

- Adaptation. How can you do it with Elaine given that you practiced with Leonard. Because Elaine doesn’t do it quite the same way. How do you adapt and make it fit this environment?

You know we want to focus on having kids show up on time. But you have got to adapt it to the local context. So part of what you’re looking for is how you’re going to make that work across a much larger area. So part of what I would say is, focus on getting all of those drivers in place. Focus on the stages, and focus on the cycles.

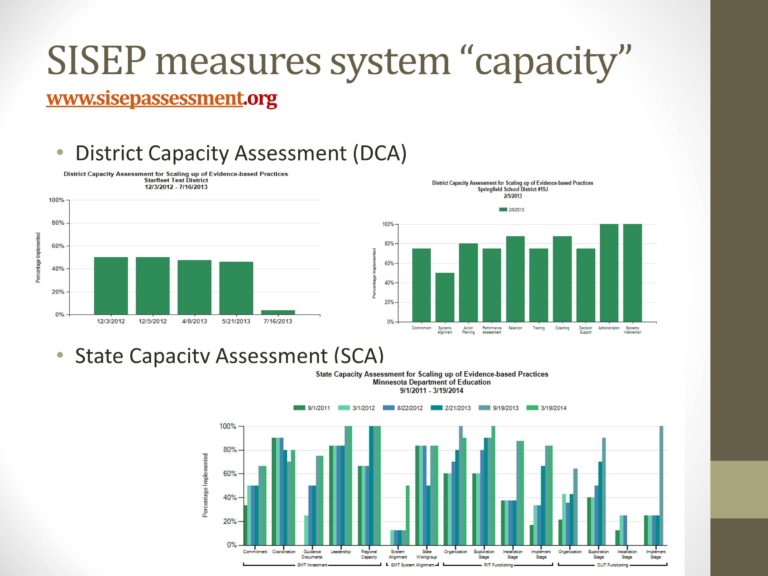

SISEP Measures System Capacity

The other part that we have learned is to really focus on measurement. We can now measure not just what happens in classrooms and schools, but the SISEP environment has taught us how to also do capacity of districts and capacity of states to implement evidence-based practices. I encourage you to to go to sisep.org to look at measures of putting that in place.

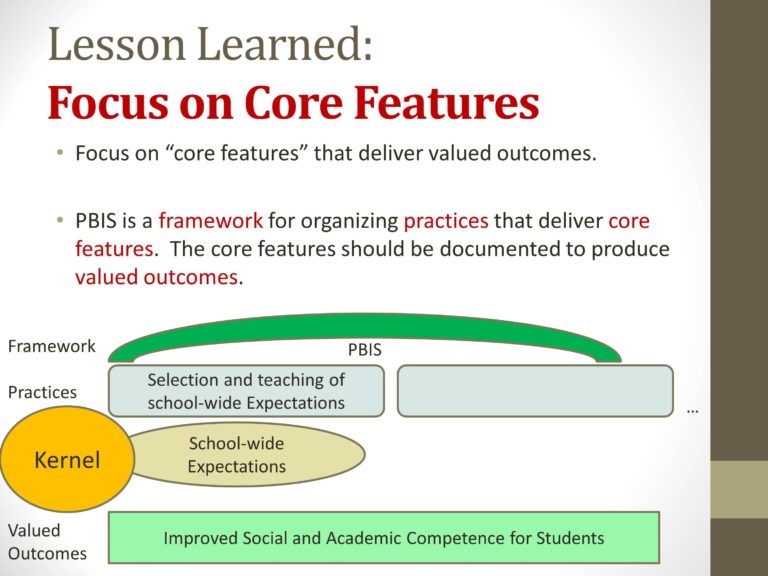

Focus on Core Features

The last piece I really want to focus on is the extent to which we implement not just practices but core features. We see PBIS as a framework. With practices that have core features that affect outcomes.

Focus on Core Features

Breaking those out, the piece that I would say is important in terms of scaling up: focus not just on the little pieces, but also the overarching pieces that make it work.

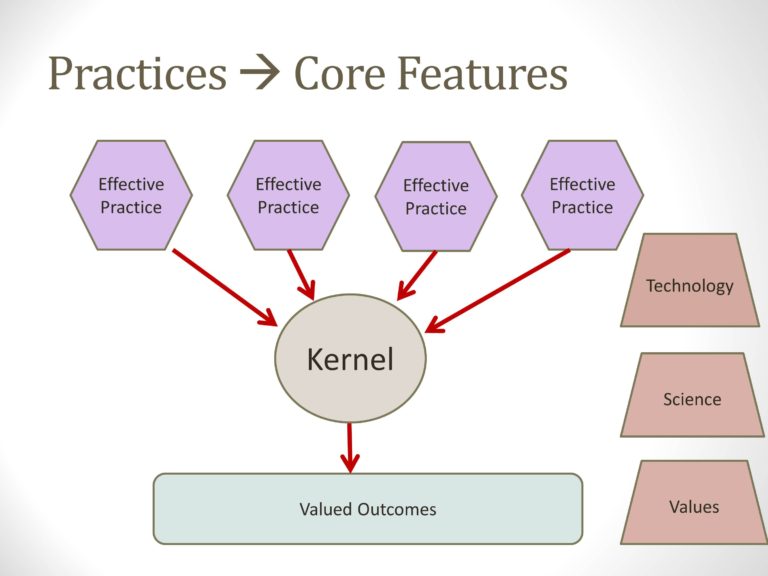

Focus on Core Features

One way to think of it is this: If you do these kernels, it frees you up to say there’s not one way to do it, there are many. And we don’t get locked into practices, we get locked into building environments that have those core features. If we do that, we can separate our values (which is what we view as the outcomes) from the science (which is what really works) from the technology of getting that science in place.

Focus on Core Features

When we identify good practices, we need to be much better at not just saying what they are and what do you do. We need to say, for whom is it intended, who needs to be able to implement it, under what situations, and what are the outcomes. We have not described our practices with the level of precision that we’ve needed in the past. If we do that, it will allow us to implement not just by asking if kids are successful, but asking if we’ve actually put it in place.

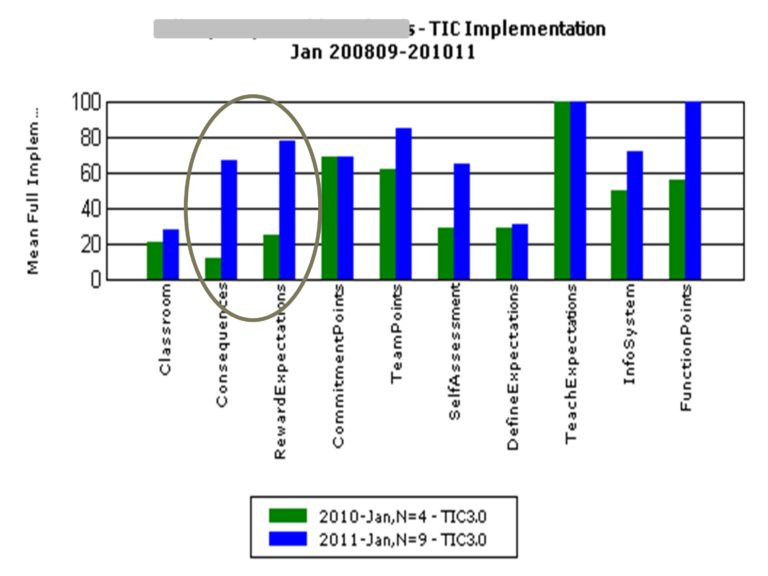

Focus on Core Features – Example

Think about this. This is a school. Look up here at the data. Think about the green. These are two points in time. The green time and the blue time. You can look up there and say, at the green time, don’t think of all the things you’re not doing right. Pick two. So let’s pick the two circled ones. Now look at the blue time. Did it work? Yes.

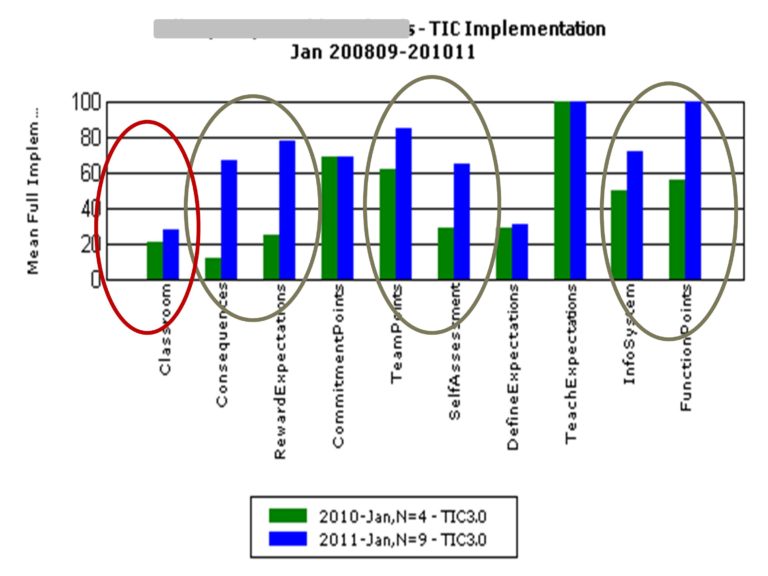

Focus on Core Features – Example

But what are you going to do next? We’re going to focus on these additional circles next. You don’t have to do everything all at once. Using fidelity as a measure is a powerful strategy for getting things in place. For 20,000 schools I can tell you that 75 percent are implementing with 80 percent fidelity.

Implement with attention to the kernels, be more flexible about how you actually embed the practices, and over and over again, if you want to implement to scale, implement with the systems that will allow you to sustain things with high fidelity for a minimum of a decade. Thank you.

Audience Question

Can you give us an example of the things that you measure?

So for PBIS, part of the core features are:

- The extent to which you’ve identified three to five positively stated behavioral expectations.

- The extent to which you have an acknowledgement system that acknowledges kids on a regular basis for doing things the right way.

- The extent to which you have a correction system that is not a punishment structure, but is a corrective feature that decreases the likelihood that problem behavior is rewarded.

We can measure that in schools by asking schools a set of questions. We go in and we actually stop the kids. We say kid, do you know the behavioral expectations? Do you know what it means right here? Has anybody acknowledged you for doing things the right way in the past two weeks?

And basically, in schools that are working well is, the kids know the expectations. They can actually tell you what being respectful means wherever they are.

The flip side is, often times we say has anybody acknowledged you for doing things the right way in the past two weeks. And they say: Oh, no. No. Teachers always think they’re much more positive environment than the kids do. But if we get the teachers asking those questions on a regular basis, they figure out – not by things we told them, but by things that they figure out on their own – how to get that accomplishment.

References

Bradshaw, C.P. Koth, C.W., Thornton, L.A. & Leaf, P.J. (2009). Altering school climate through school-wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports: Findings from a group-randomized effectiveness trial. Prevention Science, 10, 100–115. [Article] [PubMed]

Bradshaw, C.P. Koth, C.W., Bevans, K.B., Ialongo, N & Leaf, P.J. (2008). The impact of school-wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) on the organizational health of elementary schools. School Psychology Quarterly, 23, 462–473. [Article]

Bradshaw, C.P., Mitchell, M.M. & Leaf, P.J. (2010). Examining the effects of School-Wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports on student outcomes: Results from a randomized controlled effectiveness trial in elementary schools. . Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 12, 133–148.[Article]

Bradshaw, C.P., Reinke, W. M., Brown, L. D., Bevans, K.B. & Leaf, P.J. (2008). Implementation of school-wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) in elementary schools: Observations from a randomized trial. Education and Treatment of Children, 31, 1–26. [Article]

Bradshaw, C.P., Waasdorp, T.& Leaf, P.J. (in press). Effects of School-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports on child behavior problems and adjustment. Pediatrics.

Horner, R. Sugai, G., Smolkowski, K., Eber, L., Nakasato, J., Todd, A. & Esperanza, J. (2009). A randomized, wait-list controlled effectiveness trial assessing school-wide positive behavior support in elementary schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 11, 133–145. [Article]

Horner, R. Sugai, G. & Anderson, C.M. (2010). Examining the evidence base for school-wide positive behavior support. Focus on Exceptionality, 42, 1–14.

Ross, S.W., Endrulat, N.R. & Horner, R. (2012). Adult outcomes of school-wide positive behavior support. Journal of Positive Behavioral Interventions, 14, 118–128. [Article]

Waasdorp, T., Bradshaw, C.P. & Leaf, P.J. (2012). The impact of schoolwide positive behavioral interventions and supports on bullying and peer rejection: a randomized controlled effectiveness trial. Pediatric Adolescent Medicine, 166, 149–156. [Article]