Challenging researchers to consider a paradigm shift for bringing evidence into practice

The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

Introduction

I’m going to talk about from small beginnings come great or goods and talk about the notion of applied things that could actually change the direction and valence and well-being of our children and our adults in this society.

I’m either blessed or cursed — I counted up the other day that I’ve done 12 population level trials and that’s a lot. I have a lot of skinned knees and I have some hard won lessons learned that I’d like to impart with you very briefly in the course of about 45 minutes.

I’m going to talk about some fundamental units of behavioral change. I’m very interested in finding small things that make a difference because the truth is its only small things that make a difference. Otherwise, nothing would be happening in the world, because big things are ridiculously hard to do. Just try to implement national healthcare in the United States as an example.

I got interested in this because of my studies at the University of Kansas. I was very, very fortunate that Don Beyer was my dissertation advisor and Todd Risley and Montrose Wolf were on my committee along with Jim Sherman and John Wright because I was also interested in media, which is how I became involved in a very large project with Sesame Street to test a way to prevent pedestrian accidents to young children which was the third leading cause of death in the United States. Can you imagine you’re looking for a dissertation topic that no one has ever done an experimental study that was successful in, and that’s a big deal. And the prior experimental study resulted in more children dying. So one of the first things to remember if you’re going to do anything large is that you have the possibility of harm and you need to measure adverse effects. I never do a study without trying to measure for the possibility of adverse effects. Don’t believe that you’re going to cure cancer without killing a few people as a possibility, so you got to do that.

So, I’m going to talk about a testable approach for improving speech language and hearing outcomes at a population level. My very earliest work in graduate school was in the infant development laboratory where Frances Degen Horowitz and her students did all of that work that showed that babies were smart. The doctors didn’t think so, but we saw the babies and they were.

Building a “Carbon Valley”

Now, we don’t need another Silicon Valley. We need a carbon-based valley. We need a valley of enterprising people who are going to think about solving our carbon-based problems. We are not made of silicon. We are made of carbon and all life forms exist on carbon.

We have a Periodic Table and people talk about that.

So our iPhones and iPads and computers run on silicon and a whole bunch of other heavy elements and other things, but they don’t run as a lifeform.

We, however, are carbon-based and we run on carbon, each other.

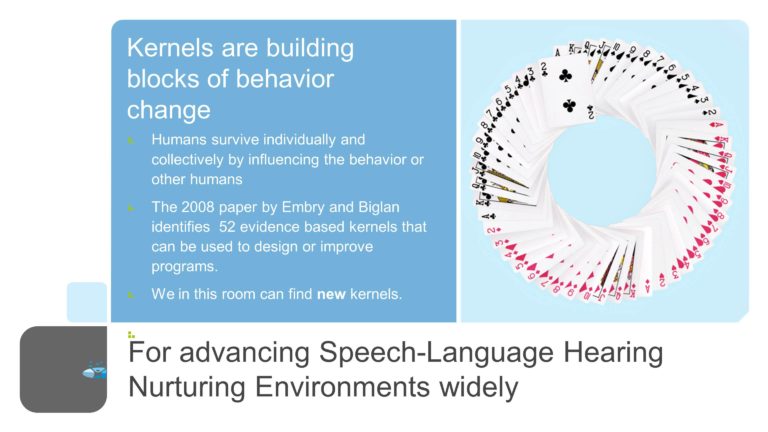

Now, what we have to do is begin to create a Periodic Table. From the Periodic Table, if you’re a chemist or an engineer or something you can create an amazing array of things but you actually know the properties of each one of those components, how they work in the world and then we begin to learn how to put them together to make something that’s completely novel that has never happened before in the universe.

That’s a pretty cool thing, but we need to think about that also in the context of speech, language and hearing. What are the fundamental units that we’re manipulating? Do we have a science for fundamental units?

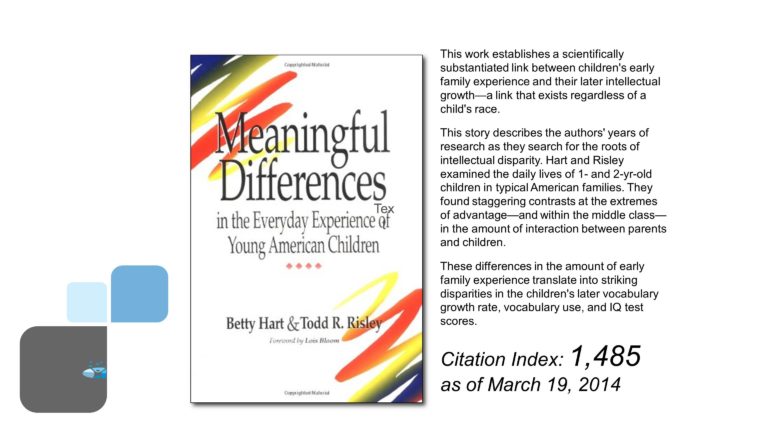

I mean I think back of Todd Risley’s study and Betty Hart’s study of the meaningful differences. That is the most amazing study in the world. Micro-coding of all of those interactions in the PD-11 computer that that was done on was on the reverse side of my office, and I could hear that damn thing operate all of the time. We had a 10 megabyte hard drive that was the size of a telephone booth. That was a big deal and it happened.

So I am arguing today for creating that Periodic Table for our work, simplicity.

Now, the Meaningful Differences study has 1,485 citations. Does anyone here have an article that’s got 1,400 citations? You know, that puts you in a world class level, okay. That’s pretty damn good. One of the most influential studies, yet we have failed to convert that into a population level practice to make meaningful differences at a large scale to improve the speech, hearing, and language of young children.

Charlie Greenwood has developed a little app. I think it works now on, or could potentially work on a phone and it can code the same kinds of things that we had all of those observers that went out in the meaningful differences study, but we’ve not used that particularly. For example there could be an app that was giving feedback to families about their meaningful differences in language composition; that’s a possibility to use silicon to change carbon lifeforms.

Now, I’d like each of you to reflect on your own knowledge. So, each of you has a vast storehouse of knowledge. I know Rob does. Pam’s got some; other people have got some pretty amazing units of knowledge about changing human behavior related to speech and language and hearing. I’d like you to think about that, think about the simplest practice that you know, something that could be taught to many people. I want you to bring that to your prefrontal cortex and hold it there.

I’d like for you to think about take a piece of paper because this is the beginning of creating that Periodic Table. Not everything we write today might convert to that, but some of them will, and some of those will become powerful golden ore pieces that could help change things. So write the name of the strategy that you can think of in your mind that’s relatively simple that improves speech, language or hearing very simple practice. Write the name of that, and then write down what do you think it increases? What would be the observable thing that you could count — either frequency or duration or intensity that it increased in speech, language or hearing. As you’re thinking about that, also think about what it might decrease, what that simple strategy might decrease in frequency, duration or intensity.

Now, one of the things I’ve learned in doing 12 largescale projects is always measure both the increase and the decrease. Always do that. They are not seesaws. We’ve proved that in our Peacebuilder study. I thought just because we increased prosocial behavior by .7 effect size with only 4 hours of in-service training I’d see almost the same reciprocal in disturbing disruptive behavior. No. Children could have prosocial behavior and be a little [gesture] at the same time. What a novel concept. So what it would increase what it could decrease?

How many people could benefit by that strategy potentially in North America? How many people could potentially benefit by this strategy in North America? Across all ages whatever you think those age categories are. That is what we would like to reach as the population number. Not necessarily we’re going to get there.

And what’s a good reference for this strategy? Just, you know, one simple reference that comes to mind. So, if you ask me, you know, what was the absolute reference that I would tell people they need to know about the good behavior game? I’d say Barrish, Saunders and Wolf, 1969.

How difficult is it to learn, to use in time, skill or other there might be a mechanical or physical resources that are required? The strategy might be very simple but perhaps it cost a $1000 to buy the equipment to do it. So how difficult is it to learn in time, skill or other?

And here’s a really important question; can it be evaluated in a single-subject design? Can it be evaluated in a multiple baseline, a reversal, a multi-probe design; there are many possible variations. Here’s why I’m asking that. Never, ever, ever, under any circumstances whatsoever undertake a randomized controlled group trial unless you have done some really good single-subject designs and you know the sources of variability. Because otherwise the variability in your RCT will kill you and eat you alive. Because you didn’t know where the sources of variability are coming from. Even if you’ve done some single subject designs, be prepared. Surprise, you’ll find out new ones as you go along.

Then the next thing is write your name and email on that piece of paper, and later today give that to our organizers because that’s going to become the sort of moving library of developing the strategies that we could take to scale. There will be others and I hope that you will nominate other ideas, but having those simple ideas rather than a big strategy. Because I’m going to suggest that we would once we have identified those small units of change in the Periodic Table now we are beginning to have a technology, a replicable technology, that could be brought to scale. And the things that you are writing about on that list are not theories. They may involve a theory, but it is not a theory. It is a thing that you could hold in your hand and learn to do. If you said psychoanalysis, I’d go that’s a great interesting book to read, but show me how I can use that with a kid today.

Creating Nurturing Environments

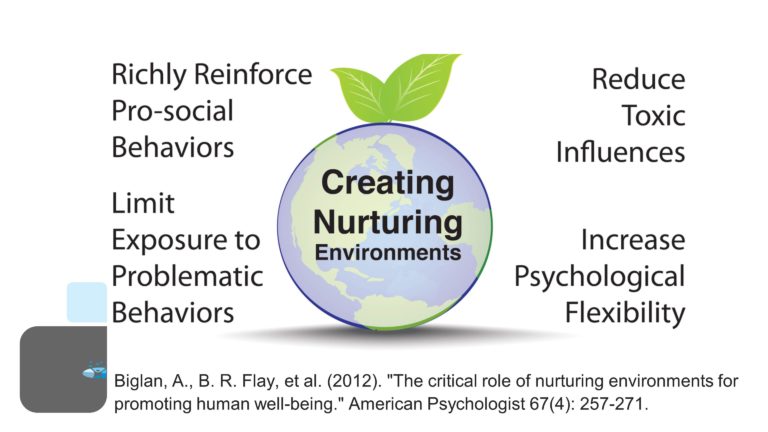

So, Tony Biglan and I and Brian Flay and Irwin Sandler have a paper published in the American Psychologist called “The Critical Role of Nurturing Environments in Human Development” and that was one of those life bucket list things to get, you know, it’s an article in the American Psychologist and I knew it was coming out and just one day I went out to my mailbox and opened it up, “Oh there’s, and oh my God! It’s the first article, wow! Score one Dennis.” So, we proposed that there are four things that are categorical to help us frame what we might need to do to make changes.

One is to create a nurturing environment and does language and speech and hearing acquisition require a nurturing environment? What did we learn from the meaningful differences study? Hell yes it requires a nurturing environment and it’s a huge effect from very tiny things. So for instance their study shows that the kids who are doing well are richly reinforced for positive behavior and their language acquisitions.

We have to limit exposure to problematic behavior. Rob over here is involved in a lot of that, in trying to reduce problematic behavior in schools. Because we know that that problematic behavior is basically contagious. The other reason we know that it’s contagious is, what is the principle predator of humans since the invention of stone tools? Other humans. And what is the principle source of safety for said humans since the invention of stone tools? Other humans with other stone tools. So understand the evolutionary dynamics that we are operating in human systems. Humans are the only species that are both eusocial and predatory of each other at the same time. That’s a very interesting complexity.

So limiting the exposure to problematic behavior. In meaningful differences we see that by the issue of folks all of the negative imperative, “Stop that, don’t do that,” those kinds of things that have sort of catastrophic effects on children’s development in increasing oppositional defiance and conduct disorders. And by the way, most mental, emotional and behavioral disorders are not disorders. They are evolutionary adaptations to when human society goes nuts. That’s an important thing to remember.

And now reduce toxic influences. Toxic influences can be social and they can be biological. One of the things is a lot of us were trained in behavior analysis and, you know, we were not supposed to touch those physiological things. Which is like, “Those are bad, don’t talk about those things.” You can’t do that! You can’t ignore a whole branch of science! So now we’re interested, for example, in what are some of the causes of the rising levels of mental, emotional and behavioral disorders which include learning disabilities.

For instance, has anyone noticed that we’ve had a major dietary shift in America? Okay. You may or may not know that one of the most significant dietary shifts that account for mental, emotional and behavioral disorders is the change in the omega-6 and omega-3 ratio in consumption even during pregnancy. So, if a woman consumes low-levels of omega-3 fatty acid during pregnancy i.e., fish, oily fish, she will likely — 32% of those woman’s children by age 8 will have development disorders, 32%. Now, if they eat oily fish only 15% will have developmental disorders by age 8. That’s in a huge study, the ALSPAC Study in the United Kingdom funded by the National Institutes of Health. So we have to pay attention to those kinds of things, and I want you understand the physiology of omega-6 and omega-3, it’s linkages, how it affects human behavior, the acquisition of behavior, the reinforcement system all of those things begin to make sense and then when you look at it in the evolutionary and anthropological context you begin to understand why some of those things were selected by humans.

For instance one of the things we know that autism; is autism spectrum disorder increasing in this country? Yes. It appears to be. I mean the first time people started talking about I only had one kid with autism spectrum disorder at the University of Kansas, and we got all those kids across the state because we were the sort of tertiary place. I only had one. Well, I learned for example that vitamin D deficiency helps predict the rise in autism spectrum disorder, which varies by latitude, and varies by skin color and diet. There’s a whole bunch of very interesting things can vary in there.

We also have to increase psychological flexibility. Psychological flexibility, this is the work, of Steven Hayes his really great work on relational frame theory. Now, I do recommend that if you try to read that book, put it beside your bed side because if you suffer from insomnia it will cure it without any adverse effects. It’s very heavy reading but important. Psychological flexibility is necessary for us to adopt and use new practices, for us to be able to open ourselves up to a new theoretical construct. Just because I was trained in behavioral analysis doesn’t mean that I should be blind to anthropological things or findings in medicine. I better be smart about these things.

Evidence-Based Kernels

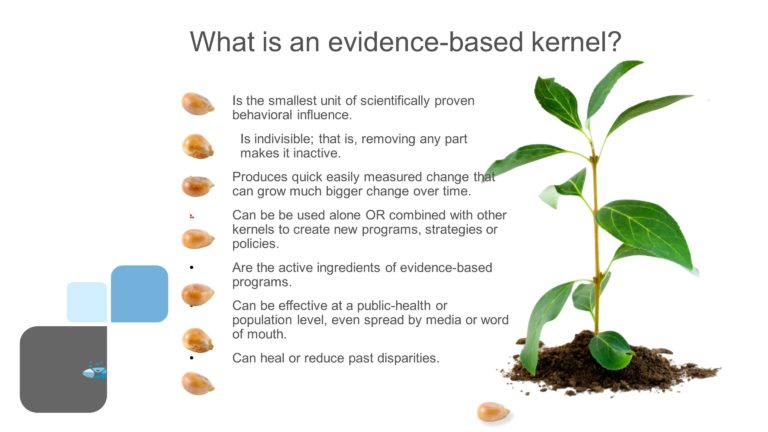

Now, Tony and I wrote a paper in 2008 called “Evidence-based Kernels; Fundamental Units of Behavioral Influence” because I’d written several papers before. I had gotten in an argument with Rico Catalano. We were arguing with this thing Tony had set up, and I was saying that you know when I get a medicine it has the label on it for the active ingredients. In our prevention science and treatment science and intervention science we ought to be listing the active ingredients and the inert ingredients cause there’s a lot of inert stuff in things. And Rico said, no, no, no because people will start to roll their own, and I said that’s a good idea. It was California.

So, we started arguing, and then one of the things I asked him — they were doing a comprehensive school reform study, and so were we, and I asked him, I said “What’s the first thing you teach teachers?” You know, what’s the first practical thing after you get done with the theory? “Oh, we teach them a universal signal for quiet, and we have them put up the peace sign and they use a chime or a bell or something like that.” And I said, “Ha, that’s funny we use the same thing except a harmonica.” “Why do you do that?” “Well, if you can’t get the children’s attention and change transition times it doesn’t matter what all the rest of the stuff is. You do this properly, you get approximately 144 more hours for meaningful responding in the classroom and teaching.” So, thinking about kernels came out of that.

Antecedent kernels would be one of them, relational frame kernels. For example for those of you who are familiar with our work in Peacebuilders, we gave the kids what’s called an I AM Manual, an I am statement: I am a peacebuilder; I praise people; I give up putdowns; I seek wise people as advisers and friends; I notice and speak up about hurts; I right/wrongs; I offer help; I promise to build peace at home and school and community each day. Very powerful when you have that kind of relational frame of identity because people start to reinforce it in each other. And then physiological kernels we’ve talked about.

An evidence-base kernel is the smallest scientifically proven unit of behavioral influence. It’s indivisible. If I take away that harmonica, it doesn’t work nearly as well. If I take away the lanyard, it doesn’t work as well because I’ll be leaving the harmonica over there and I’m here, so I lose time. The lanyard make sure that’s around my neck to remember it. The sound is soothing because children often with developmental disorders, if you use a chime or a bell the high frequency sound just causes the alert circuitries in the brain to register a nuclear attack. So it produces quick and easily measured change that can grow bigger change over time.

Think about when you’re doing something. If you’re saying, “We’re doing an intervention, and it’s going to take 6 months to see any measurable change” you better rethink it, because you should be able to see micro-measurable changes in days or weeks maybe even minutes. Because that’s how nature works.

Now, they can grow and they can be used alone of combined with other kernels to create new programs or strategies. And most of the active ingredients, if you look at the list of the national registry of effective programs and practices on NREPP, most all of the ones with the highest level of effect size have, if you go back and read their bibliography, they have essentially evidence-based kernels that were all tested in single subject designs. So they have lots of active ingredients that are easily noted. They can be effective at a public health or population level, even spread by media or word of mouth, and they can help heal or reduce historic disparities.

I go to these damn adverse childhood experiences things; how many of you have been to one of those things? You all heard about adverse childhood experiences, the Kaiser Permanente Study, well just go sit through a day of that. Then people sort of forget they keep running on, “well you want to do that over in the Title One schools,” and “You need to remember that was done on middleclass working people in Kaiser Permanente.” So this is everywhere. It’s like a disease and trauma informed treatment. We’re just going to be, you know, we’re going to have a special ambulance every day running to pick up people. So better start thinking about trauma-informed prevention. We’ve got to think about those disparities.

Now, in our paper we stopped at 52. We realized there were more, but it was really cute because we essentially had 4 suites and 52 cards, and you can rearrange them and you can make almost anything with those 52 cards. But I know there are more, and I hope that you will contribute to the foundational knowledge that can be stored and grow here in the Foundation so that we would have a toolbox that could be shared to scaffold and build new interventions.

Now, the Ivory Tower has been used to designate the world or atmosphere where intellectuals engage in pursuits that are disconnected from practical concerns of everyday life. People ask me, “Are you in a university?” And I said, “No, I can’t stand departmental meetings it’s being bitten to death by docs.” And I recently had one of those experiences. I am a co-investigator at Johns Hopkins and we had a meeting, the foundation wanted to do a nutritional supplements study in Baltimore schools. I do a lot of work in Baltimore schools, and so I brought Joe Hibbeln who is the leading scientist, he is the chief of the Molecular Membrane Laboratory and the Nutrition Laboratory National Institutes of Health. He’s a smart dude and Adrian Raine, if anybody knows him, he’s another super smart dude. Those people talked, and we were being bitten to death by ducks, “Well the children in Baltimore should get their omega-3 from wild salmon.” I’m going “Have you been to a school cafeteria in Baltimore? Have you see the bodega’s where they get their breakfast, you know, it’s essentially deep fat fried Hostess Twinkies.”

We need to bridge, we need to visit the other archipelagos of the Ivory Tower. The other little islands as David Sloan Wilson refers to them. He wanted to do all this prevention thing, and he didn’t know anything about prevention science, met Tony Biglan and then the rest is history, so we are you know resistance is futile.

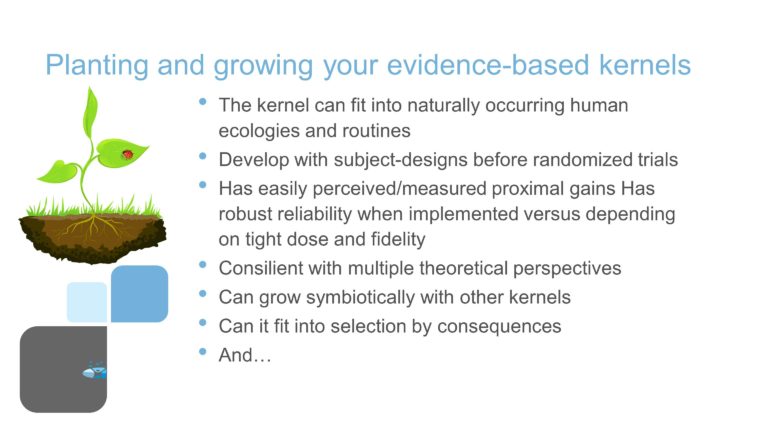

So, now planting and growing your evidence-base kernels. Once you have an idea that something small like this might work, okay. Could you combine it with other things? So, for example, could you combine this with another kernel called Beat the Timer and another kernel called the Premack Principle? How many have heard of the Premack Principle? Okay. Oh, it’s a delicious thing in schools. You know, you can, we have over 500 prizes based on the Premack Principle for rewards in schools. Don’t have to use stickers, don’t have to use stamps, but for example in first grade we might draw out of the jar and it’s a mystery motivator so you don’t know what it is in the box and that makes the dopamine circuitry go absolutely wild, anticipating. It’s based on the principle of gambling, so in first grade and there’s whole industries on these things.

Okay, so we have let me introduce you to a Granny’s Wacky Prize that you can use. Please stand because you’ve been sitting for about 45 minutes or an hour. Howard come out and you’re going to be my partner, okay? So, I’m going to show you a Granny’s Wacky Prize a simple thing. So, you guys have just done something that earned this teacher’s recognition. You have been working your butts off for like 45 minutes, and have been completely paying attention to the guest lecturer Dr. Embry. So, as a special thanks we’re going to have Granny’s Wacky Prize. Shake the box. Oh my God! The amazing Olympic race. So here’s how we do it: I will blow my harmonica for start. And with your partner, you start to run the race. It’ll be a 10 second prize. Midway we start, we have to get faster and faster, and when we go across the finish line — that’s when harmonica sounds — we jump up and give each other a high five. Alright, you ready! Get set! Go! [Harmonica sounds] Alright a little faster! Come on we’re going to get there! Oh! We’re almost there! We’re there! Yes! Oh! Yeah!

That was cool, right? By the way, that also has a physiological effect on you. So, Joseph Donnelly at the University of Kansas has done this amazing study showing that interspersing the day with these brief physical activities not only decreases BMI — it’s the only school-based thing to decrease BMI — but it also; what do you think it does to academics? Improves academics. Why? Well, it changes the brain chemistry. That’s the place where people are most sedated, if you will, sedentary in their daily lives as kids. Movement creates brain derived neural factor, without brain derived neural factor you can’t learn a damn thing because the operant stuff won’t wire. You need, I tell the teachers B, D, and F brain derived neural factor is essentially brain fertilizer. And with brain fertilizer you can do Hebb’s Law: neurons that fire together, wired together, okay?

So, now they can be developed in single subject designs that have easily perceived and measured proximal gains and has robust reliability when implemented versus depending on tight dose and fidelity.

How easy would it be to implement something like a little box with those kind of prizes? Super easy. And who’s going to come up with ideas for it? The kids. So, you’re going to have an infinite supply of ideas for it. And by giving it a cute name — if I called it the Premack Principle, it just doesn’t have good mouth feel. So, you know, making it, giving it a cute name always thinking about the relational frames and the marketing of your tools. Never name your tools after the problem you’re trying to prevent. This is a serious mistake by most people in designing programs.

The robust reliability is really, really good. Does it matter for example if the Granny’s Wacky Prizes are in a box? No. Could they be in a bag? Okay. Could they be in a jar? Could they be in a leftover Halloween treat kit? Yes! Do they have to be on slips of paper? No, you could maybe even put it up on the Smartboard. That’s robust implementation rather than rigid, dose infidelity.

They have to be consilient with multiple theoretical perspectives. This is why I hate departmental meetings. My micro-theory is a slightly bigger than your micro-theory. And you know we’re measuring now things the size in nanometers rather than yards or miles or kilometers. I want to measure big things in time, but the small things do make a difference but you’ve got to connect the things and do the crosswalk. So, do you think for example in explaining to teachers that Granny’s Wacky Prizes is based on the Premack Principle? That’s good, but what really hooks them? When I link it up to brain science. You know, I got my medical people, saying oh that would be kind of cool to test that out and get, by the way can I come and do some of your scanners, I’d really like to do that?

So, can it grow symbiotically with other strategies? Can we marry them? By the way the transitions go from 2 to 5 minutes a piece down to about 10 seconds a piece; I can show you videos of that, and there are 50 transitions in the course of a day in an average elementary school. They normally last those 2 to 5 minutes, so that’s at least 100 minutes a day of no opportunity — well there is opportunity to respond, but the responses are none of the things that we want in this room. They interfere with all of those things. But can they grow symbiotically? So, we compare this with Granny’s Wacky Prizes, kids you save us so much time, you know, let’s have a little bit of fun. So, we’re now, we’re rewarding effort, and we’ve used two things very simply to scaffold something.

They can fit into selection by consequences. In the recent paper that we have in “Brain and Behavioral Science” we talk about selection by consequences as a major conceptual metatheory, so Hebb’s Law, neurons that fire together, is selection by consequences. The Granny’s Wacky Prize is selection by consequences. I’m going to show you a state-level interrupted time series design that uses selection by consequences to reduce tobacco use in minors. So, that’s a scalable thing, and of course the amount of money that you receive in research grants in promotion and tenure is selection by consequences. So, you’ll be able to come up with other things.

Some kernels and combination of kernels are used often and may improve the indicators of well-being. We use morbidity and possibly mortality. You know, that’s a phrase for when some of these things are used a lot. They’re not programs. This is not a program. So, I struggled to figure out a name for things that were naturally occurring. What Todd and Betty observed with meaningful differences was not a program, perhaps it was programmed by evolution but not a program. Open your manual to page 101 and read the instructions there — it wasn’t like that.

So, what are things that might be protective that you use on a daily basis? And the paper poses one of the first ones, the analogy we give. How many people here have had a baby? How many people here were a baby at some point? Okay. You owe your life to Ignaz Semmelweis. In 1840, he had three maternity wards and he noticed that the wards that were maintained by the physicians had very high maternal morbidity: about 26% of the moms died with childbed fever. But he noticed that the maternity wards tended by midwives didn’t. They only about a 1%. But he noticed that they always washed everything. So he undertook a little experiment, he used tincture of chlorine which we, you can buy as a product at Target and Walmart and grocery store that’s called bleach, Clorox okay? So, we did this in an interrupted time series design across three maternity wards. First maternity ward he does it with the tincture of chlorine; mortality drops down to 1%, stays that way. No change in the other two maternity wards. He decides to try a different variation, so he tries tincture of carbolic acid, which has the same properties of being an antiseptic. They didn’t know about germs, and whack, mortality is down. And then he does the next one. He presents all of this to the Viennese Medical Society and they promptly have him put in a mental institution because it’s Eve’s curse that women die in childbirth. Do you hear the psychological inflexibility? Of course it was true, and there were other people who had replicated this same phenomenon but they didn’t have the Internet then. Took 40 years for this to become common practice. That in my paper I argue is the first experimentally tested behavioral vaccine. You use seatbelts, you brush your teeth, you put gates across the stairwell for your babies, the electric little plug sockety things those are behavioral vaccines, things where repeated daily reduce the risk of mortality and morbidity and/or increased well-being.

So, a lot of what we do in speech and language and hearing are not programs. They are essentially behavioral vaccines made up of kernels used every day. It’s important for us to change our thinking from programs to explain these things as something that you do every day. Because, will a child if they have a 10-hour program in speech and language be changed for life? Probably not. They might have an improvement, but you got to repeat, you know, I can’t just brush my teeth once. Or wear my seatbelt once. It’s an everyday thing to do these things.

Population-Level Influence

So, now here’s an example of an evidence-base kernel recipe as a behavioral vaccine. We have a relational frame.

In Wyoming and Wisconsin we do the right thing by not selling tobacco to minors. That is the language of promotion. We have mystery shoppers which is an evidence-base kernel. The mystery shoppers go to the store, and do mystery shoppers look for the good or the bad? They look for the good. Because if you’ve done the right thing you get some kind of maybe not a Granny’s Wacky Prize but you get a gift certificate and an atta boy and atta girl kind of thing. So the mystery shoppers went out and reinforced the clerk and store, and they did it on public posting so we had a scoreboard every day for every single county in Wisconsin and those were announced on the radio station. So the kids who did the mystery shopping let’s say they were in Eau Claire, Wisconsin and they called the morning AM show. Every community has a morning AM talk show. So they call up and “Hi, this is the Wisconsin youth team, and we’re out at Bill’s Bait Shop at Lake Woggy Noggy. And we just want to tell you that Bill’s Bait Shop did the right thing by not selling tobacco to us minors, and they’re helping our youth be healthier and happier for their whole lives. So ring that bell on your radio show” Ding, ding, dong you know the cow bell rings, and we gave out cards to all the elected officials who that with their names printed on it that they could give to the managers of the stores or the clerks thanking them for doing the right thing. They said, “Well, how do we know if they’re doing the right thing?” I said, “We’ve gotten the rate down to less than 5% of the time that they’re selling tobacco. So you’re going to be rewarding most of the people and the poor shmuck who gets the card from you that sold is going to be reminded, oh this the community norm, hum.”

So, what did that do? This was a study done by, originally by Tony Biglan and it’s a small scale study and we did this across two whole states and here’s the rapid thing. So, Wyoming had 60% of the time the kids could buy tobacco, in 45 days we brought that down to less than 10% of the time. That saved, by the way, 3 million dollars in penalties. In Wisconsin they were at 37% of the time the kids could buy it, we had a shorter period of time and Wisconsin was 10 times larger, and 70 counties, and we only had 40% of the counties initially. We brought it down under the threshold and eventually it went down to less than 2% and using the Youth Risk Behavior Survey that the CDC ran in both states we were able to reduce any 30 day use of tobacco substantially by trajectory, and everyday use in Wyoming substantially. This was confounded in Wisconsin because they increased the tax on tobacco the year we just did that. It may have had an effect here but notice the tax did not affect experimentation, which is what you would have predicted.

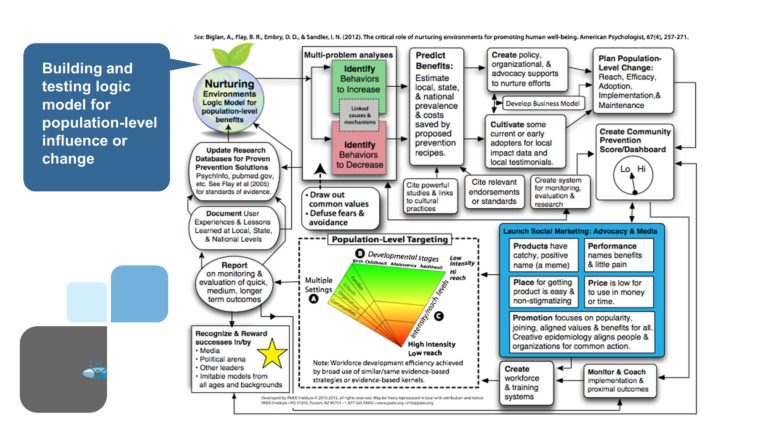

Now, here is a logic model that we created for doing things to scale that begin with small kernels. So, once you know these kinds of things and you’ve identified the behavior that you want to increase and behaviors you want to decrease, then you have to predict the benefits that are going to happen in a population. Nobody’s going to buy your thing unless you tell them how it’s going to scratch their back. And scratching their back may be time, money, whatever, but you don’t go telling them necessarily how you’re going to solve the problem in the universe. You got to tell them how it’s going help Brian. Or Brian’s organization.

And then what have to do is create the policy and advocacy supports to nurture that, you have develop a business plan. Oh my God! They don’t teach you that in graduate school. But it must have an operational business plan, besides getting another grant.

Cultivate early adopters for local impact data and testimonials. If you don’t have the testimonials, you will not be able to close the deal. And just because somebody in Los Angeles said it was a good thing, is not going to persuade the cabinet in Manitoba that it’s a good thing. I got to drag up some bodies from Manitoba that are going to say it’s the best thing since sliced bread. And you got to cite relevant endorsement standards because people say, “Well how does this fit in to Common Core?” I call that Common Gore actually.

Cite powerful studies and links to existing cultural anthropological practices. So that people can go “Well yeah, we sort of do that. Yeah we’re just going to tweak that a bit.” It’s a shaping thing.

So, and then create a population level plan I’ll just briefly go through that: create a public scoreboard. You have to have a social marketing component here. There are actually five components of a social marketing thing. There’s population level targeting so you have to also think about when you’re doing a bigger thing, how do you ramp it up and down. Because if you’re doing a universal, you’re going to have to have some adaptations for higher intensities because not everybody is going to work on thing and just don’t leave it to chance.

You need to have reinforcement and recognition systems and you have to have a monitoring system that is providing real-time feedback; think back to the applied behavior analysis studies.

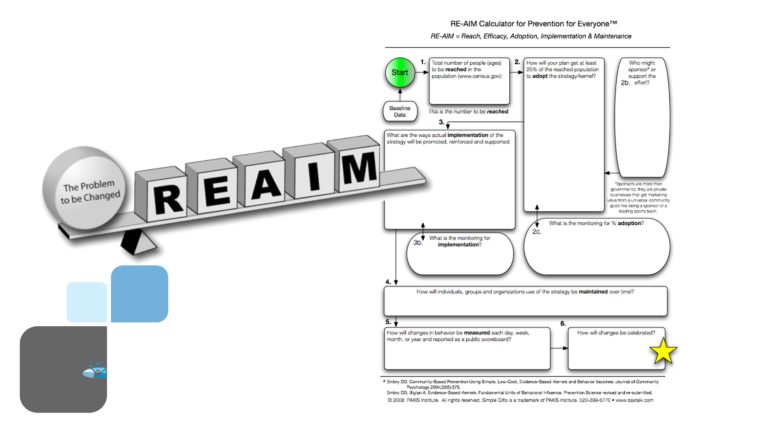

So, there’s a REAIM thing, that’s stands for Reach. You have to Reach a large number of people, at least 20%. You have to have Efficacious things that really work. You have to get a fair number of people to Adopt it. They have to Implement it and Maintain and the measurement of it. Those are the formula for these things.

Just briefly, this is one of those things. This is one of the most cited studies in behavior analysis. It’s a citation classic, it’s the good behavior game. Thousands of citations for it. It went unused at a population level. It was invented by a teacher.

So Johns Hopkins did longitudinal studies on this after it was well-established.

There were 20 interrupted time series study before the longitudinal studies, so we really knew it worked. The random assignment, they only got it for one year.

No more GBG.

Those kids have been followed through age 19 and 21, 26 and 30, and there are now five independent replications of the longitudinal study. And it has dramatic effects, you can see that on NREPP.

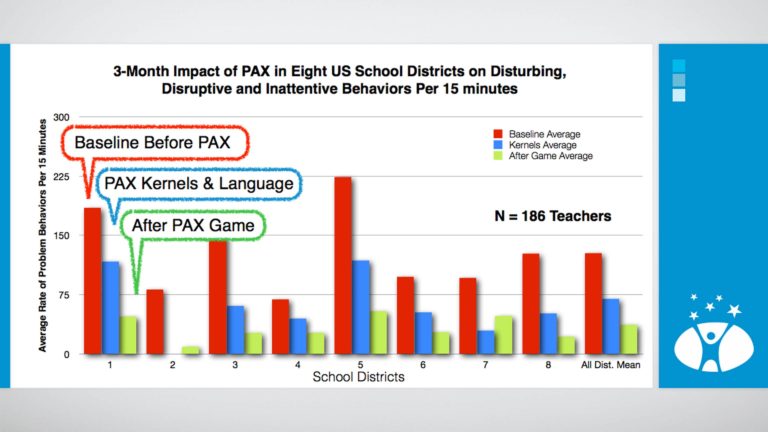

We’ve been able to show that you can take it to scale. This is a 186 teachers, in 3 months, in 8 diverse school districts across the United States that were selected by the Federal Government and said, go do your stuff. So you have to show to the payer that you can rapidly deploy that.

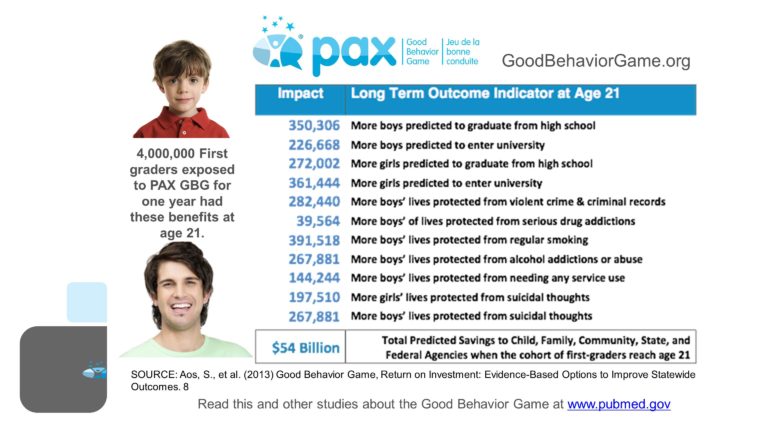

Now, what is this do for America because we have this healthcare problem? You mentioned it. All of these costs, all of these things that are rising. So we have cost estimates from the Washington State Institute for public policy. We’ve translated their gobble de geek into something that people can understand. So, this is what it would do if every first grader — we have about 4 million first graders every year — what it would do at age 21.

We have now computed that for every single congressional district. Why? Because that’s where policy gets made. For every state, and you can compute it for every school district, and so we have to start thinking about putting our numbers like that.

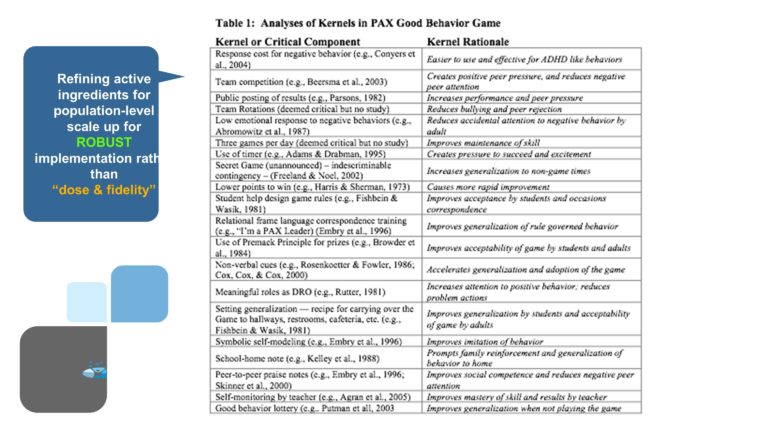

We’ve also done an analysis and added to the good behavior game to make it survivable in the real world. Because I can tell you when I first did my first replication of it was a complete utter miserable failure and did not work because the people said, I ain’t touching that thing.

You also have to be prepared to do media and so on. You have to learn to market things. Don’t depend on an advertising company to do it, you have to understand that.

Next Steps

So next steps, we need to create and test those evidence-base kernels, build that library.

We need to move from small beginnings to greater good as St. Francis of Assisi said.

And our real hero is Benjamin Franklin who founded the Leather Apron Club. The Leather Apron Club was completely different than any other scientific institution in its existence at the time. They met every week, discussed things, and then set about creating a practical plan to test their ideas.

All of the other science was affectation in Europe. The people who did the experiments or did the data collections were never the people who were writing about it, so they had no firsthand knowledge. So, this, they invented the Franklin stove and other kinds of things which transformed America. In this country we have the American Intellectual Movement which was unique, the Transcendental Movement, the Logical Positivism Movement which all of that science has created us in this room. So, we have to go back to our roots and think about that practicality.

We need to bridge our ivory archipelago. We need to recognize that we’re in new territory.

For example, epigenetics. How many of you had a course in that in graduate school? And that’s the rage and we need to understand how we are actually changing that in our behavioral interventions.

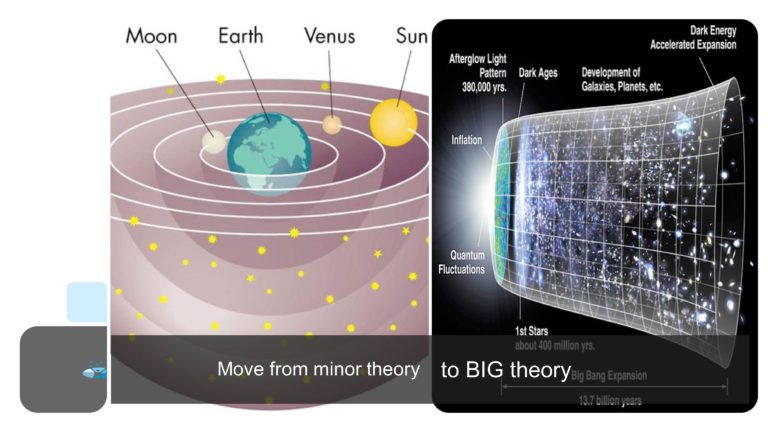

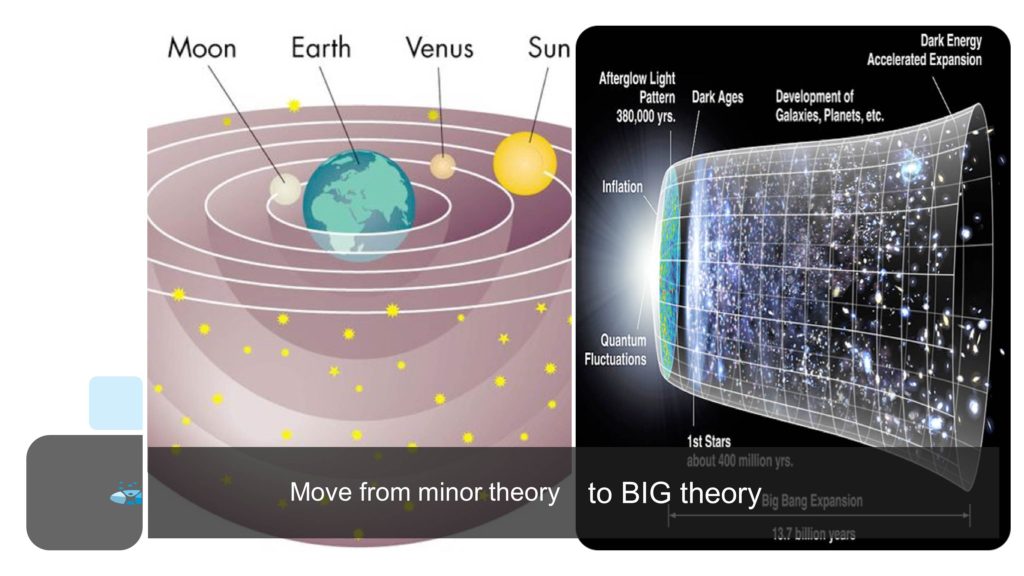

We have to move from our minor theory, our pet theory. You know, that the earth is the center of the solar system. Our little theory is the center of the science. To the Big Bang.

We need to consider the sheer joy, the sheer joy of being able to do something great for speech, language and hearing for our children’s futures, for our futures. Thank you very much.

Questions and Discussion

Question: Clearly at some point you leave the evidence-based trail as you mix kernels together. You probably don’t have the time or money to test all those permutations. What is the method to get from kernels to packages and feel like you’re still walking the evidence-based walk?

It’s a great question. So, the answer is continuous measurement. For example with PAX GBG, we have an operational measurement system that is measuring essentially engaged minutes — which is opportunity to respond. And we’re measuring the rate of disturbing, disruptive behaviors per hour. It’s a coarse one, but we use that as we do new permutations to keep looking at that. We’ve done this in more than 650 schools; thousands of classrooms, all 38 states, and now to Canada, Ireland, Estonia, etcetera. So we use those data to look at them, and we’re very alert for problems. And then you kind of tweak the permutation. The first thing we look for is the rapid rate of adoption, and then the sustainability

The other thing that we’ve done, and I suggest you do this, is never go for large print runs unless they’re dirt cheap. Because you’re going to wind up throwing away a whole bunch of paper. That way you can make incremental improvements. We use demand digital printing for our manual. Now, we’ve actually gone to offset because we’ve gotten it stable enough that it’s pretty reliable. That doesn’t mean that we don’t want to make changes, but we’re doing that very carefully. So have your ongoing measurement system that’s both for proximal outcomes and process outcomes. We created a rubric to measure those kind of implementation factors, and then monitor that and then every now and then.

We’re also very attuned to spontaneous innovations that people do. Some of them suck. Some of them are fantastic. One of them was a teacher, when we were observing in Syracuse. Normally the teachers announce what the disturbing, disruptive — we call them spleems, that’s a relational frame that controls the physiology. But the teacher asked the kids to predict what would be PAX (the good) and spleems before they played a game, and then asked them to debrief after. And as soon as I saw it, “Oh my God that’s self-regulation right there. We’re putting that in now. Why didn’t I think about that?”

Question: Looking at interventions, there is a great deal of reward to individual clinician researchers to develop an intervention that has their stamp on it, that’s associated with them. Having been involved in some projects that look at related interventions for a particular area, you see these common elements that I think could vie for status as a kernel. How do you break down the tie that people have to their particular package?

That’s an excellent question. Part of how you do that is that you really focus on the psychological flexibility things, and pay attention to the work of Steven Hayes in the Adoption of Innovation. You put people in contact with their real core values of what they’re trying to do. So, when we’re working for example with schools, we ask them, “What are the things that you want to increase and decrease? And what would you see, hear, feel and do differently if those things happened?” Then we asked them, “What is it that you want to pack in your children’s suitcases for life as they go away 20 years from now? What do you not want in those suitcases for life?” And then we keep going back to those core values, and that helps people move through the difficulty of “it’s mine, mine, mine.”

Audience Response: I think that is most helpful with individual clinicians. But that it’s harder for researchers who have developed a set of studies to support the package.

I solved that for myself. I had a publisher, and my publisher was rigid because they had 10,000 copies in a warehouse, and I knew that the manual needed to be shredded. Whenever you do this, give yourselves degrees of freedom. Make sure that you never sign a copyright transfer that’s forever. If you do a publisher, make it have a limited term so that you can renegotiate or kill them if you wish. I chose to kill them and start doing it myself, and the great thing was I had total control, and I made a hell of a lot more money, and I was able to exercise my dedication to making the change and promoting the change. So I can’t answer your question fully, but it’s a complicated one.

Question: You probably noticed you got a real reaction out the audience when you said, “Always do a single subject design before you move to an RCT.” A lot of us really love our single subject experimental designs, but most of us have also found that our grant reviewers don’t really love them. Do you have any tips on getting that practice through the levels of scrutiny from other fields that are not as positive about those methods?

Tony Biglan and I have been working on that with NIH. For them, in their preliminary studies, to really encourage people to do single subject designs. We’re making a little progress. A couple times when we put them in, we didn’t get trashed. And it helps if you also say, “Oh yes and we can actually convert these findings into an effect size” and there’s literature on that. Most of the people in there who are the RTC folks have no knowledge of the statistical manipulations that are possible. Also talk to the project officers before you submit to a particular one. Sometimes you can just go do it and use it as your preliminary study, and you have a publication to cite — they’ll never read the publication anyway, but you’ll get your money more likely. I didn’t really answer your question. But we just have to keep pushing the envelope.

I did have a breakthrough on this. The Assistant Secretary’s Office for Planning and Evaluation asked me to write a document with Mark Lipsey on how to create programs when there were no programs. That paper really spells out and that’s free online. [Best Intentions are Not Enough: Techniques for Using Research and Data to Develop New Evidence-Informed Prevention Programs, 2013]

Question: I was intrigued by your connection between Silicon Valley and Carbon Valley. When I think about Silicon Valley, I know one of the mantras was “Fail big, fail often.” How does failure fit into innovation and answering the questions that we want to have answered in Carbon Valley?

By the way, our first venture in to creating the carbon-based valley is Wright State University and we did a retreat for two days with them about this, and we are now actually doing this research now in pre-service training for both teachers and for human services people. But to answer your question, I’ve had several big failures and they were terrible, they were catastrophic. I was completely ill, but damn they made me smarter in how do things. And I think we need to present adverse findings as extremely helpful rather than to discard them. Maybe we ought to have a finding of fail small, fail big — here is the lessons learned from that. You know, the first study on traffic safety was done by Sweden, and they taught kids, preschoolers to cross the street midblock, I think because somebody made the stupid error of believing police reports for what children did. The police people wrote down “A kid killed crossing street midblock.” No, if you went and did direct observations, the kids never crossed the street. But they did enter the street in the course of play, and that was an essential understanding then to design the intervention.

References

Aos, S., Lee, S., Drake, E., Pennucci, A., Klima, T., Miller, M., Anderson, L., Mayfield, J. & Burley, M. (2011). Return on investment: Evidence-based options to improve statewide outcomes [Document No. 11-07-1201]. Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy.

Barrish, H. H., Saunders, M. & Wolf, M. M. (1969). Good behavior game: Effects of individual contingencies for group consequences on disruptive behavior in a classroom. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 2(2), 119–124 [Article][PubMed]

Biglan, A., Flay, B. R., Embry, D. D. & Sandler, I. N. (2012). The critical role of nurturing environments for promoting human well-being. American Psychologist,67(4), 257 [Article] [PubMed]

Embry, D. D. (2004). Community-based prevention using simple, low-cost, evidence-based kernels and behavior vaccines. Journal of Community Psychology, 32(5), 575–591 [Article]

Embry, D. D. & Biglan, A. (2008). Evidence-based kernels: Fundamental units of behavioral influence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 11(3), 75–113 [Article] [PubMed]

Embry, D., Lipsey, M., Moore, K. & Mccallum, D. (2013). Best Intentions Are Not Enough: Techniques for Using Research and Data to Develop New Evidence-Informed Prevention Programs. [Issue Brief]. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services.

Hart, B. & Risley, T.R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Paul H Brookes Publishing.

National Registry of Evidence Based Programs and Practices (NREPP). (2015). Good Behavior Game (GBG) Intervention Summary. NREPP: Find an Intervention(Available from the NREPP Website at http://www.nrepp.samhsa.gov/).