Defining the scope of a broad research-practice framework which sets the context for presenting the major gaps from research efficacy to implementation

The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

Introduction

At some point a number of years ago, I decided that what I want to do when I grow up is to work to try to increase the quantity and quality and value of implementation science.

This was based on some experience within the department of Veterans Affairs and the VA QUERI initiative and its work to increase the impact and the uptake of research to improve veteran healthcare. And I recognized through a series of conversations with colleagues that the clinical research is not enough. These findings and innovations are not self-implementing, there is a science of implementation. And that science, as I indicated, needs a fair amount of effort to increase, as I said, both the quality as well as the quantity.

As a consequence, each time I’m given an opportunity to speak and participate and contribute to a meeting like this, it’s a chance that I jump at.

Obviously the close proximity to my home base in Los Angeles, as well as the beauty of the setting were factors as well. But I do appreciate the opportunity.

My task is a little bit different, and someone more mundane I suppose, than that which Dennis was given. And that was to provide a set of frameworks and ways of thinking about what is implementation science, why is it important, how do we go about thinking about the design and conduct of implementation studies.

And perhaps more importantly, what is it about the field in the way that we are conducting our implementation studies that has left us in a situation of somewhat limited impact. We have a very large body of work, but I think it’s fair to say that if we take a half-full versus half-empty sort of perspective on the field, we’re very much on the half-empty side. We have much to do. The impacts and the benefits of the increase in quantity of implementation science activity haven’t yet realized or yielded the benefits that we need.

Much of my talk will focus on presenting a set of frameworks and a set of answers to the question: Why is it that implementation science work has not yet led us to, some might say, a cure for cancer as a way of highlighting the difficulty and the challenges associated with the problem.

But I think it’s fair to say — and I know many of the speakers over the next couple of days will reinforce this idea — it’s fair to say that we could be doing things somewhat differently in order to enhance the value of what we do.

As I said, though, I began at the VA, the US Department of Veterans Affairs, affiliated with the QUERI program — a Quality Enhancement Research Initiative — and that was a program designed to bridge the research-practice gap, to contribute to the VA’s transformation that I’m sure most of you are familiar with during the 90s, and to try to focus the efforts and energies and attention of the health services research community within VA on the problems and issue of the transformation healthcare delivery system. Primarily due to health reform, all of a sudden within the health sector we see a great deal of comparable interest outside VA. So I’ve been in the position of essentially representing or carrying some of the insights and trial and error learning experiences from VA and systems like Kaiser Permanente, the UCLA Healthcare System, that are interested in trying to understand and replicate what VA accomplished and to do so in perhaps two to three years, rather than 20 to 30. I’ve been given opportunities to help share some of those experiences.

In some ways I often feel somewhat like a management consultant. Back when I was in business school getting a PhD, the MBA students used to talk about the management consultation occupation and the job opportunities — and the shorthand label or description of that occupation was that a management consultant essentially steals ideas from one client and sells them to another. In some ways, that’s what I do lately between VA, Kaiser, and UCLA. But it’s all with full transparency, they both recognize the contributions as well as the benefits, and I think it’s all above board.

So let me move on and provide you with what I feel is a summary of the key topics or the categories of knowledge that I hope will be covered during the conference, and that to me represent basically what the field of implementation science is all about. My hope is that at the end of this conference, you have a very good sense as to what implementation science is, what its primary aims are, what the scope of the field is. Why is it important? What are some of the key policy, practice and science goals for the field?

How does it relate to other types of health research? And as a researcher with a PhD, a social scientist working in a health care delivery system and health setting, the bulk of my work and what I know about is health. I know the work that you do is at the intersection between health and some of the social services and other sectors. So if you will excuse my focus on health and perform the translation in your own minds from clinical and medical issues to the broader set of issues, that would save me from the burden of trying to do that on my own, and speaking about issues that I don’t know much about.

In addition to the question of how does it relate to other types of health research, one of the key areas of focus of the QUERI program and my presentation will be item number four. What are the components of an integrated, comprehensive program of implementation research? What are the kinds of studies that we need to think about in order to move from the evidence, the kernels, the programs to implementation and impact? That is a bit of a challenge, in part because the components of the integrated, comprehensive portfolio are somewhat different from what we see in other fields.

And finally, the broad set of questions. How does one go about planning, designing, conducting, and reporting the different types of implementation studies? I will not touch much on that issue at all, but that is the focus of much of the other talks.

Dennis covered the first two issues. What is implementation science? Why is it important?

What I’d like to do is focus primarily on questions 3 and 4. I will spend some time talking about number 1 and some time about 5 as well. My focus again will be primarily, how does implementation science relate to other categories of health-related research, social science/social service research And what are the components of an integrated program?

Implementation Research

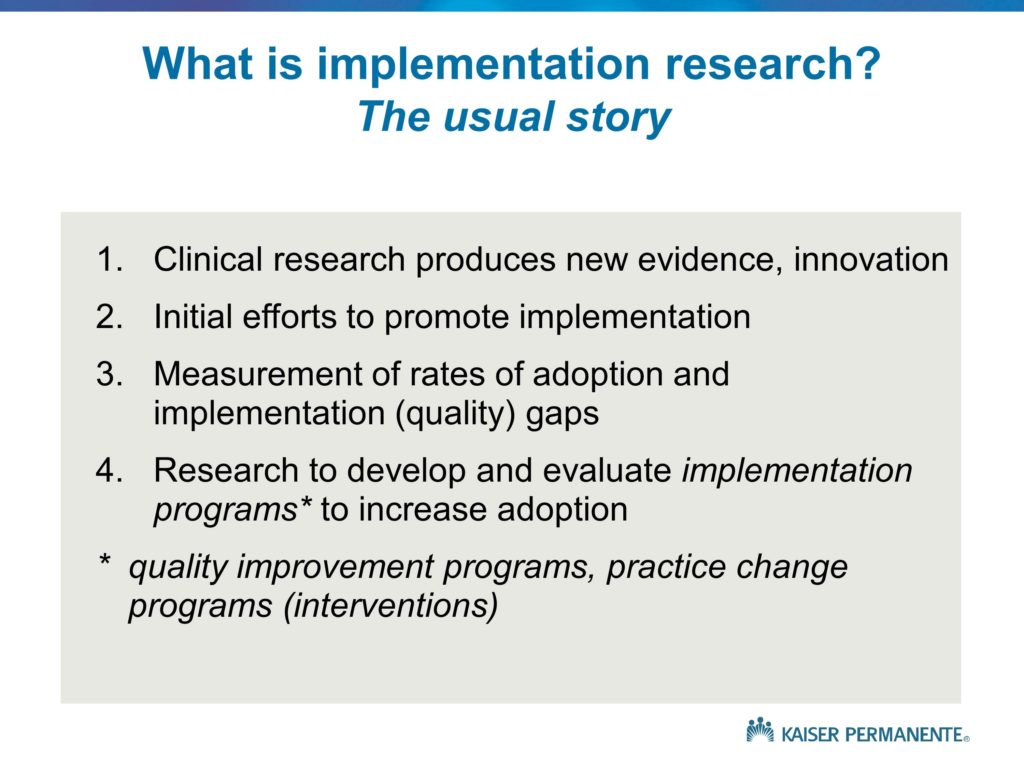

Let me go through a set of slides that provide different ways of thinking about what implementation research is all about, and why it’s important. These are all somewhat different, but largely complementary. This is the usual story that we see, and the usual way that we think about implementation research. And it’s a story that for the most part does not have a happy ending.

I’ll say more about that in a minute. But generally speaking, what we see is the introduction or development, the publication of a new treatment, a new innovation, new evidence. Often, at the time that that innovation is released, we do see some modest efforts toward implementation. Most of those efforts focus on dissemination, increasing awareness. We see press releases that follow the publication of the journal articles. In the health field, we often see greater impacts on clinician awareness when studies are reported in the New York Times or Time Magazine than in the original journals. There are often editorials that are published that accompany the release of the new findings that point out the importance of ensuring they are adopted and used by the practicing clinicians. But by and large these are relatively modest efforts towards implementation, and they focus primarily on dissemination, increasing awareness, with the assumption that awareness will lead to adoption and implementation — an assumption that we know, by virtue of all of us being in this room, is not valid.

A number of years later, we will often see articles published that measure rates of adoption and for the most part show that significant implementation gaps or quality gaps exist. So, yes, there was the publication of this large, definitive, landmark study. Yes, there were press releases, efforts on the part of specialty societies and other professional associations to publicize and increase awareness. There were, at best, small increases in adoption. And often times there are no increases in adoption. That finding — the documentation of those quality and implementation gaps — is the usual trigger for implementation studies. And those implementation studies tend to be large trials, often without the kind of pilot studies and single-site studies that Dennis talked about, that I will discuss briefly as well. Those are large trials that evaluate specific implementation strategies or programs, practice change programs, quality improvement strategies that attempt to increase adoption.

And the reason this story typically has an unhappy ending, is those large trials of implementation strategies tend to show no results. Not only do we see a lack of naturally occurring uptake and adoption, but even when we go about explicitly, intensively, proactively trying to achieve implementation, more often than not — or more often than we would like — those effort fail. It’s that unhappy ending that I will talk about with some of the frameworks and try to explain what it is about the way that we are going about designing, conducting, following up on and reporting on implementation studies that may contribute to those disappointing results.

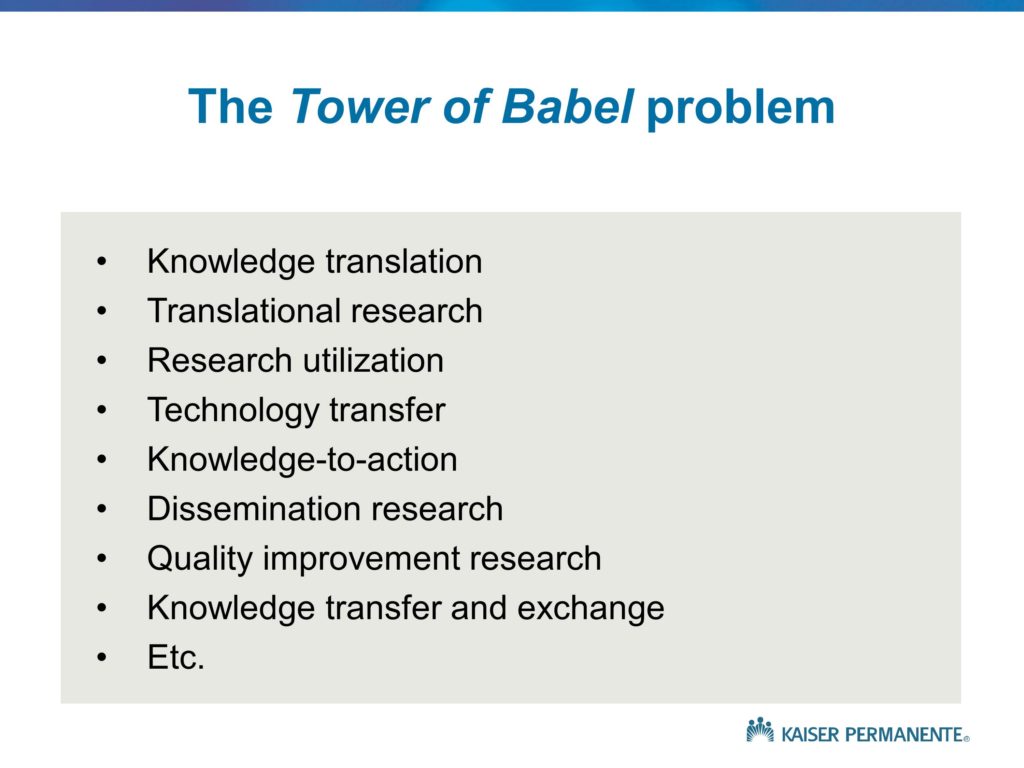

I’ll also point out that implementation programs or strategies, quality improvements or practice change programs — there are a number of different terms, and I tend to use the interchangeably, and I’ll actually talk a little about the so-called tower of babel problem as well.

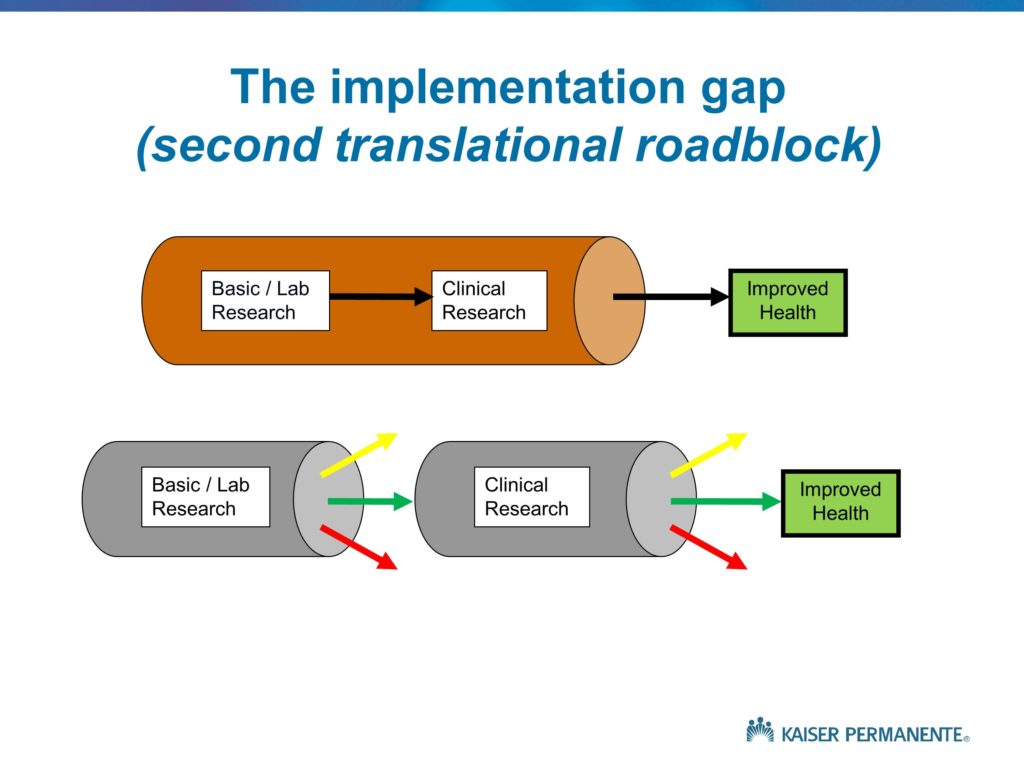

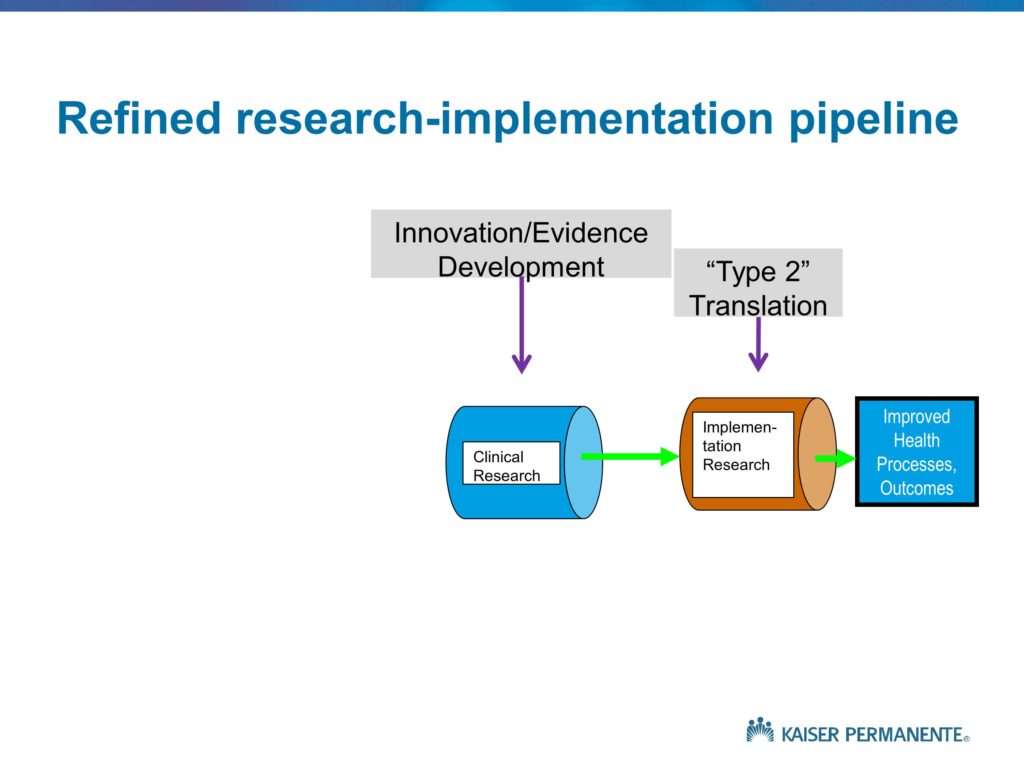

Let me go through a set of slides, again, that provide a number of slightly different ways of thinking about what implementation research is all about. This is a set of simplified diagrams that really derive from some work of the Institute of Medicine Clinical Research Roundtable about 15 years ago, as well as the NIH Roadmap initiative, again in the medical-health field. They basically depict the distinction between what we would like to see in a well-functioning, efficient, effective health research program. That is, basic science and lab research that very quickly leads to clinical studies that attempt to translate those basic science findings and insights into effective clinical treatments. Some subset of those clinical studies do, in fact, find effectiveness of innovative clinical treatments. They’re published, they’re publicized, disseminated and we see the improvements in health outcomes.

As opposed to that idealized or preferred sequence of events, what we tend to see is depicted by the bottom set of arrows. The yellow arrows, if you can see those, depict the idea that some proportion of basic science findings, as well as clinical findings, in fact should not lead to subsequent follow-up because they don’t have any value. There is no reason to follow up. A treatment or therapeutic approach that we evaluate for which the harms exceed the benefits is one that should be published, should be well-known, but of course will not lead to improved health. So the yellow arrows are to be expected, they are appropriate.

It’s the red arrows we would like to eliminate. The findings that are published, that have some value, that sit on a shelf for some number of years and then eventually are taken up and moved into the next phases.

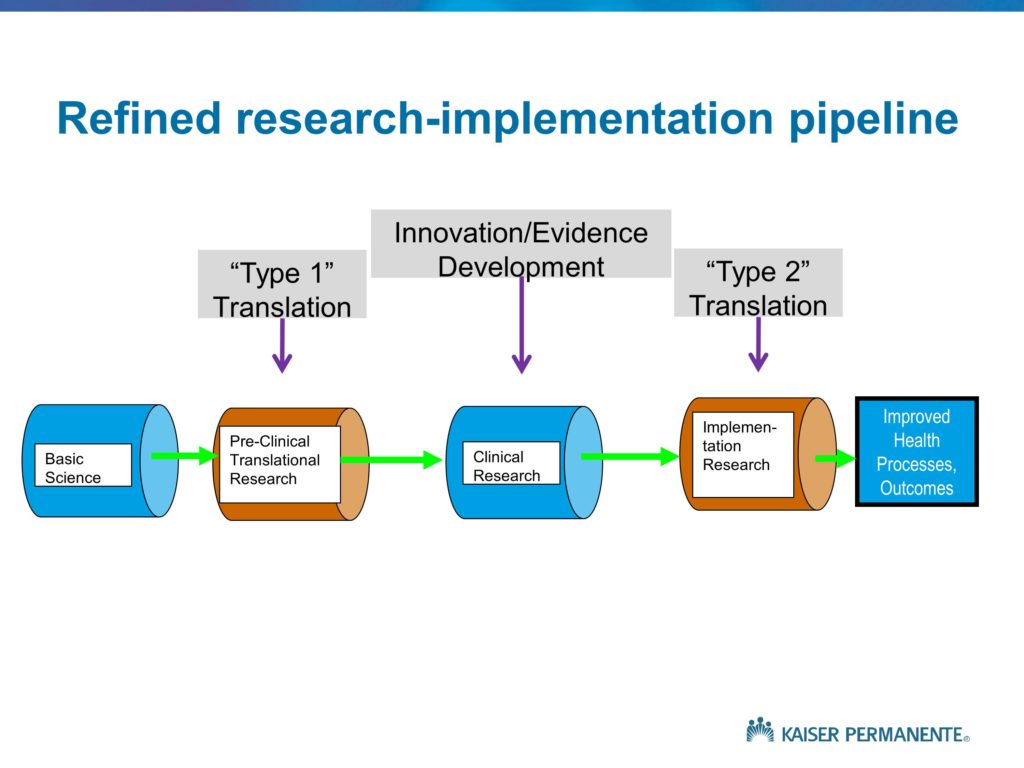

This is just another way of depicting these different activities. Of course, in the NIH Roadmap initiative — and those of you who are familiar with medical school and university campuses that have funding for a CTSA or CTSI, the NIH Clinical Translational Science Award program. The bulk of that funding, and the bulk of the NIH investment, as is usually the case, focuses on Type 1 translation. Translating basic science findings into effective clinical treatments. Some label this feeding the pipelines of the drug companies. I won’t spend any time down that path. But the point is, much of the NIH investment is on the Type 1 translation.

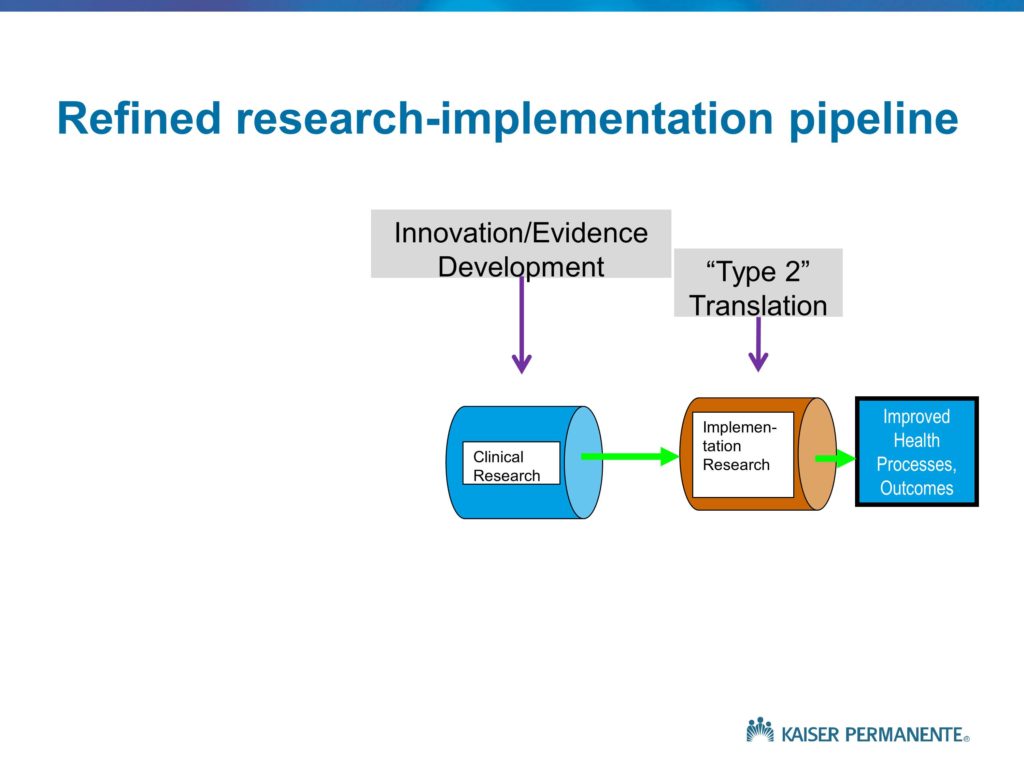

Our interest, of course, is in Type 2 translation. Understanding the roadblocks that prevent a significant proportion of the innovative treatments and findings from clinical research moving into clinical practice or achieving their intended or hypothetical or potential benefits and impacts.

So, for the rest of my talk and the rest of the conference for the most part, the focus will be on this so-called Type 2 translation — the second translational roadblock.

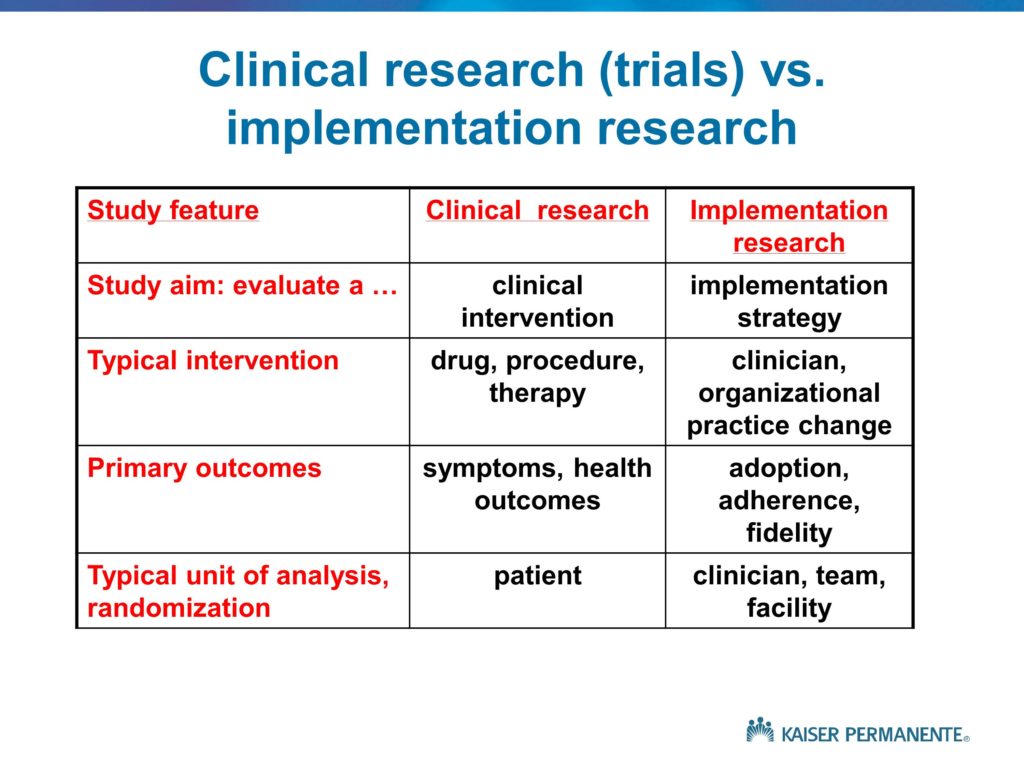

One of the important distinctions, and a distinction that is often not clearly made in research, is between clinical research, or clinical trials, versus implementation research. This is one table that attempts to capture some of the key features of both categories of research and helps us understand when we are conducting clinical research, when we are conducting implementation research, and when in some cases we’re conducting hybrid studies that combine elements of both.

For the most part, the study aims of a clinical study, a clinical trial, are to evaluate a specific clinical intervention — a treatment, a therapeutic approach, a prevention approach, management of a condition. The focus of those studies is on the effectiveness or the efficacy of that clinical intervention. These are drugs, procedures, different forms of therapy. The primary outcomes that we hope to effect through clinical studies, through the use of this clinical treatment, are symptoms and health outcomes. The unit of analysis is that of the patient. So we are evaluating a new therapeutic approach, a new school-based program, violence prevention, any number of kinds of programs or interventions. The term clinical research is used somewhat broadly to capture that type of research.

This is in very distinct contrast to implementation studies where the focus is not on the clinical intervention, but instead on an implementation intervention — a practice change, a quality improvement intervention. Our focus in this case is on the adoption and the uptake, the use of that clinical intervention by the clinicians, by the teachers, by the counselors, or by the organizations — the institutions, the entities that are delivering that program. In this case, our interest is ultimately in achieving improvements in health symptoms and outcomes, but that’s a distal outcome and goal. The proximal outcome and goal of the implementation studies is to improve rates of adoption. Improve adherence to an evidence-based clinical practice guideline, improve the fidelity of delivery of that program. Of course in this case, the unit of analysis is not the patient, but instead the target of the intervention, and that is a clinician, a therapist, teacher, counselor, a team, a facility.

This set of distinctions is important in clarifying what we are doing, what are we trying to achieve, and the reason in part to be very clear about this distinction is that different theories, different kinds of research designs, different evaluation approaches, different outcomes measures are applicable to clinical research versus implementation.

These are distinct categories of research. Though again, it is possible in some cases to combine elements of both. But if that is done — and I’ll talk about hybrid designs in a moment that are hybrid effectiveness implementation studies — it’s still important to distinguish the aims, the goals, the outcomes, randomization, and so on.

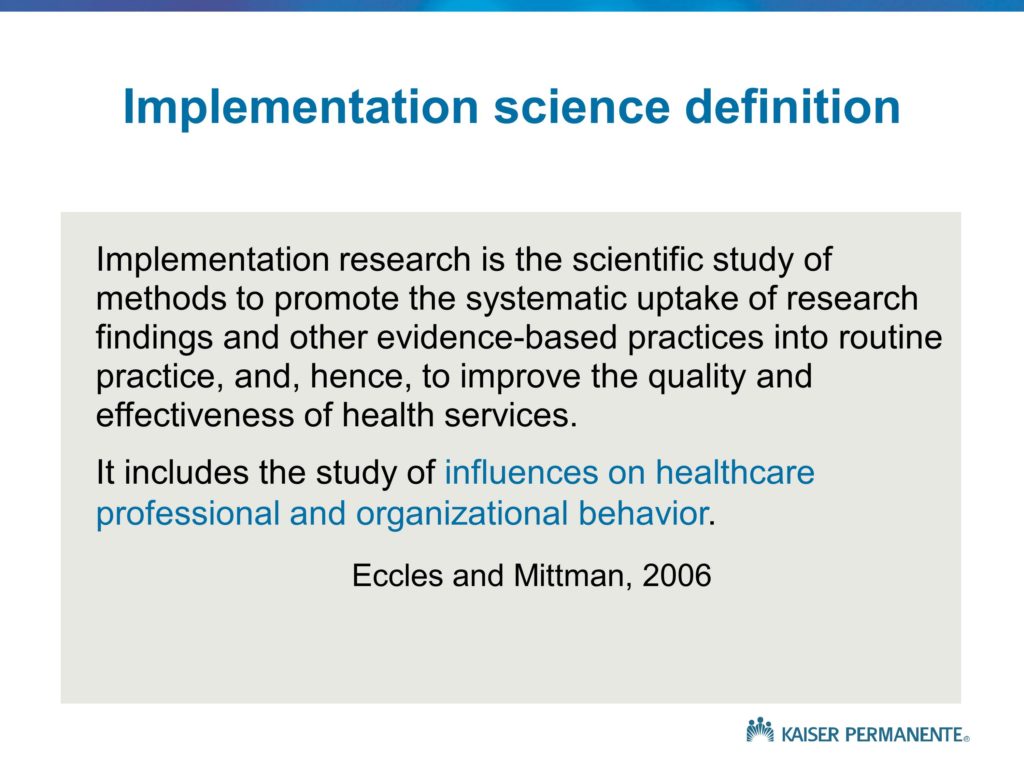

Yet another way of thinking about implementation science is the definition that Martin Eccles and I published in the opening editorial to the journal Implementation Science in 2006. And this was adapted from previous definitions. It’s a two-part definition. The first part states that implementation science or implementation research is the study of specific methods or practice change strategies to promote uptake of research findings and practices into routine care settings. The goal, of course, is to improve the quality, the effectiveness, and the outcomes of health services.

Implementation science also includes the study of influences on healthcare professional and organizational behavior. I’ve highlighted that in blue because, in fact, when we were debating the title and scope of implementation science we had a great deal of discussion — and actually not as much consensus as would have been ideal — over the definition, over the term, and over the scope. We decided to use the title Implementation Science, but in fact it would have been more appropriate for us to label the journal Implementation Science in Health because the focus of that journal is on health, and it in some ways ignores the fact that there is implementation science in a number of other social sectors in other fields and domains. Dean Fixen was among those who was most vocal in advocating a broader scope. For a number of reasons including the fact that the publisher we decided to partner with — BioMed Central — was a biomedical publisher, we decided to limit the scope on health. But there has been continuing debate, and the global implementation conference that Leslie and Nancy had mentioned where we first met did have a broader scope. We continued to debate within the implementation science and health field how much effort we should make to reach out to our colleagues in other sectors. One argument states that there are too many differences in those sectors to allow for productive interactions, and it would be more confusing than beneficial to collaborate and try to achieve cross-fertilization. My response and my view is this: if we were doing fine on our own in the health field, it would be okay for us to say, we’ve got this covered, let’s not confuse ourselves. The fact is, we don’t have it covered. There is a wealth of insights and approaches that we could begin to import and benefit from in other fields, and we actually should be doing more of the sort of thing that you are doing right now — which is to bring together a group of individuals who come from different fields and begin to exchange better ideas. I saw an announcement just recently for the 2015 Global Implementation Conference — which I hope many of you will have an opportunity to attend and contribute to this cross-fertilization process that we sorely need.

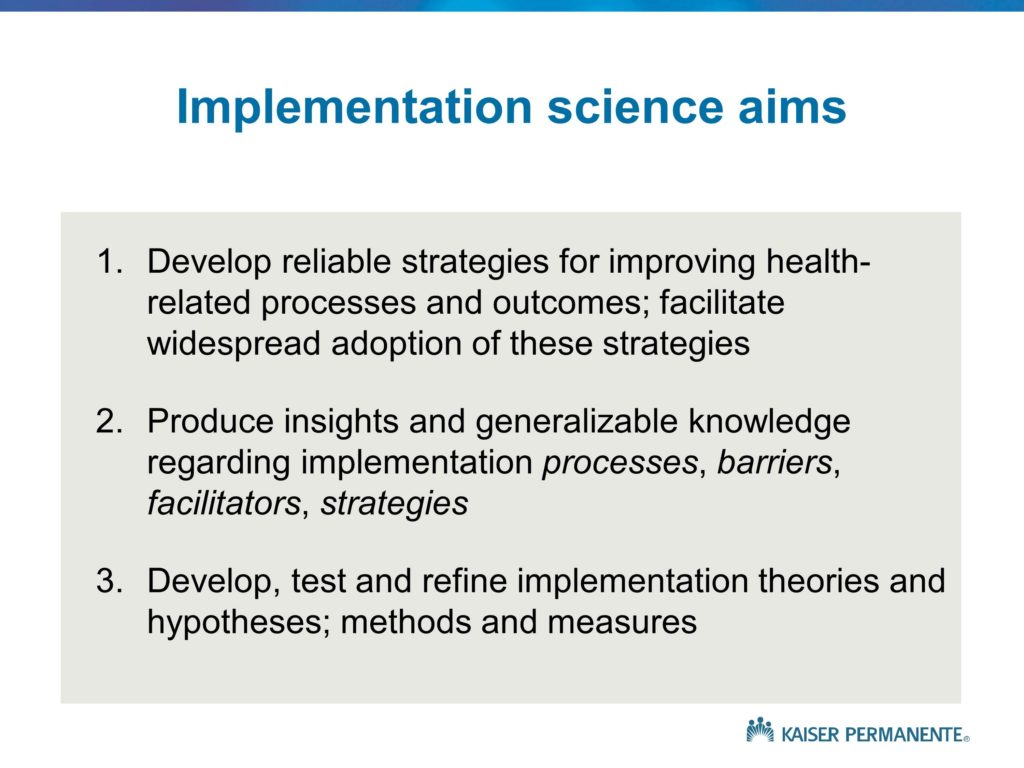

So, this is a re-statement of the definition of implementation science, which again is a way of trying to convey what implementation science is all about. I believe if we were to go back and perform some sort of content analysis on the last two to three or more years of publications in the journal of Implementation Science, the vast majority of them would fit very nicely into one or more of these categories.

Implementation science aims to develop strategies for improving health-related processes and ultimately outcomes, and to achieve the adoption of these strategies. This aim maps to the first definition on my previous slide. It focuses on the interventions, the practice change strategies.

The field also, though, as more of an observational or basic science orientation and set of aims to produce insights and knowledge regarding implementation processes. How does implementation occur in natural settings, under natural circumstances? What are the kinds of barriers and facilitators to implementation, to greater adoption of evidence-based practices — effective practices? And what are the specific strategies that we can employ?

Finally, as with any field of science, implementation science aims to develop, test and refine theories and hypotheses and to develop methods and measures.

Again, another way of thinking about the question: What is implementation science all about? What is its scope? This is one answer to that question.

I had mentioned earlier the Tower of Babel problem. It is continuing to plague the field. It has to do with the historical origins of the field, but basically does represent an impediment to greater progress. We see far too much work published under different labels. There are competing kinds of arguments or views or philosophies here. One of which says, look the field came from a number of different origins, all of us in the field just need to take the time to become familiar with these terms so we can find the research and understand what our colleagues are doing and to integrate that research ourselves.

The counter-argument, which is the one I subscribe to, says, we have a problem that is not only one that is internal to us, but also external. We need to clearly state what it is that we do to highlight and to explain its importance and to achieve better recognition and legitimacy and support. We can’t do that if we are speaking different languages. We need to somehow forge some sort of consensus and limit the scope of terms that we use.

I have another issue with what I often refer to as the t-word. Translation. That comes from a number of concerns, one of which is that Type 1 translation and Type 2 translation are very different kinds of research. Using the same term to describe both leads to confusion. The other problem is somewhat different, and that is that there is an implication when we say knowledge translation — and this is not necessarily an implication that is perceived by all — but to me it has the feeling that we as researchers and academics possess knowledge that we need to translate to our, perhaps, less capable policy and practice colleagues. Now, knowledge transfer and exchange actually gets around that by talking about and implying that there is knowledge on both sides, and we need to transfer and exchange, but knowledge translation tends to imply this issue of a one-way transfer of knowledge and a translation to a dumbing-down of that knowledge. For all of these reasons, I’ve been on — what seems at some times to be a bit of a one-man campaign to stamp out use of the t-word. But I think for the sake of clarity and consensus and consistency to present a unified front to our policy and practice colleagues and other stakeholders, it would be very beneficial for us to try to reduce the number of terms and to reach some consensus on what this field is all about. The result of this debate within the planning committee and the launch of Implementation Science, the journal, of course was implementation science rather than other terms.

Let me briefly talk about one other area of confusion. One other area that requires more work and more thinking in efforts to forge consensus. That is the distinctions between implementation research or implementation science and quality improvement. There are a number of differences, and again there are as many different opinions on these issues as there are researchers active in the field, or nearly so.

For the most part, quality improvement tends to focus on specific quality problems that need to be addressed and solved right now. A common approach to quality improvement is to continue in an iterative manner to try different solutions until we solve the problem. It’s a valid and appropriate approach because, as will become clear later in my talk, but especially in some of the others, the breadth of barriers that we face, and the number of different solutions and factors that influence successful practice change is very large. We rarely can correctly guess the first time out what it is that we need in order to close a quality gap, to change a practice. So we do need to continually try new things, evaluate their effect, and in this rapid-cycle, iterative manner continue to work until we solve the problem. That’s, in some sense, what quality improvement is all about. It’s motivated by a quality problem, and you need to solve that problem.

Implementation science tends to be motivated, or to begin not with a problem but instead the solution — the evidence-based innovative practice or innovation — and the idea that that innovation, in order to achieve its benefit, requires proactive efforts to achieve implementation. So, it starts from the solution and forges ahead in the practice-change direction. As a scientific field it attempts to develop and rigorously evaluate an implementation strategy across multiple sites, not solving a single quality problem, and to do so in a way that is generalizable, and to develop generalizable knowledge at the same time.

In the interest of time, I’d like to go on. There will perhaps be time later on during questions to debate this more thoroughly, but again it’s another area of somewhat limited consensus and confusion within the field that relates back to the Tower of Babel problem.

Gaps in the Pipeline

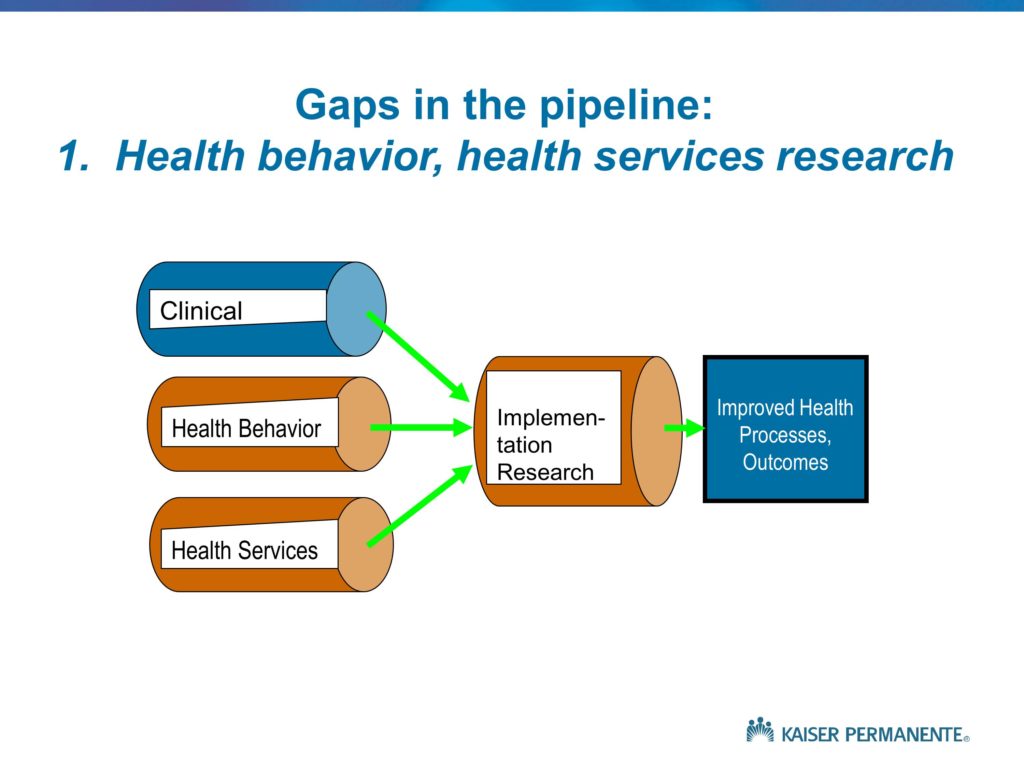

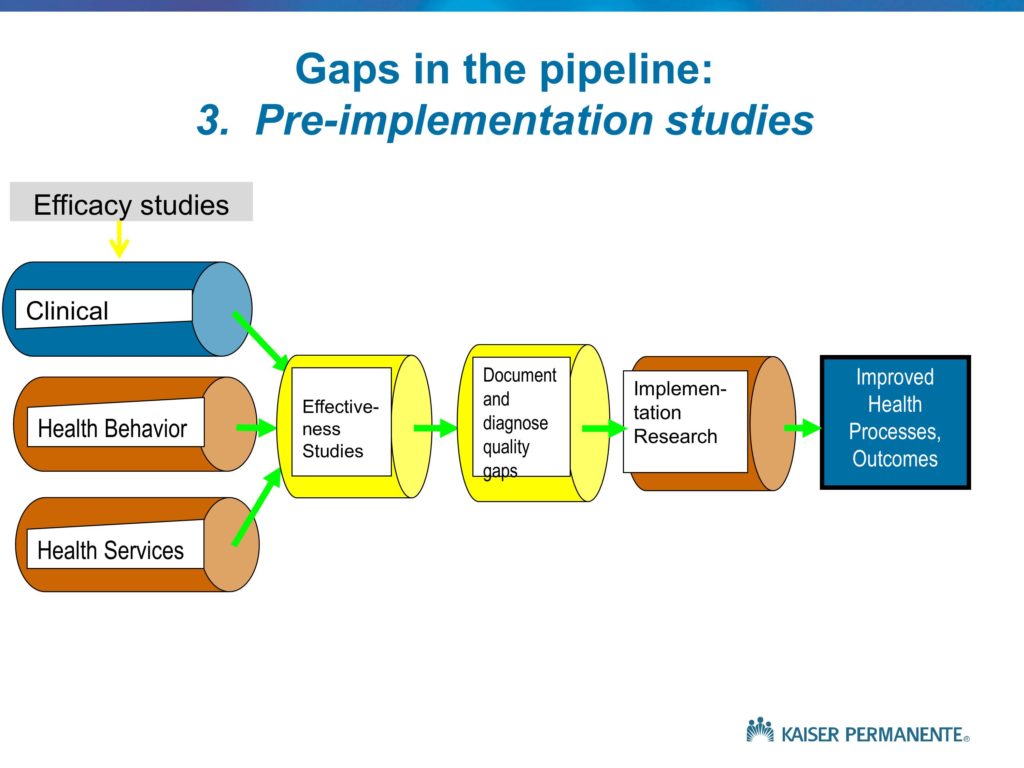

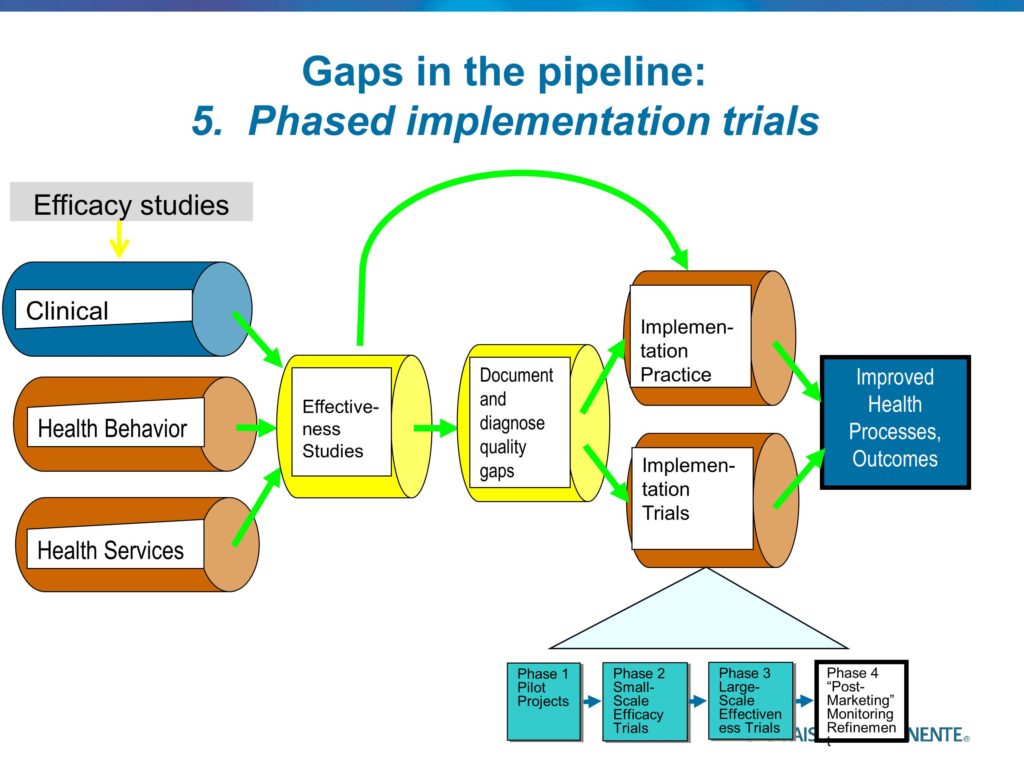

Let me return to this diagram, then go through a set of slides that attempt to illustrate some of the gaps in the pipeline — some of the reasons why this very simple linear sequence is often not effective in closing implementation gaps and leading to increased adoption and uptake of the evidence-based practices that we attempt to sell and purvey.

The first gap in the pipeline is our thinking about what we mean by clinical research. In some ways this is not a gap, but simply an elaboration or an explanation of what I mean when I say clinical research and what that center of that main, large pipeline is all about. It’s not just clinical research on drugs and devices, but health behavior research, health service research. Much of the work that you do would fall under the health behavior category. But again there are many other categories of clinical efficacy and effectiveness research in different bodies and different domains in social service sectors that are generating new innovations — innovative treatments and strategies. That is all the focus of what I label clinical research.

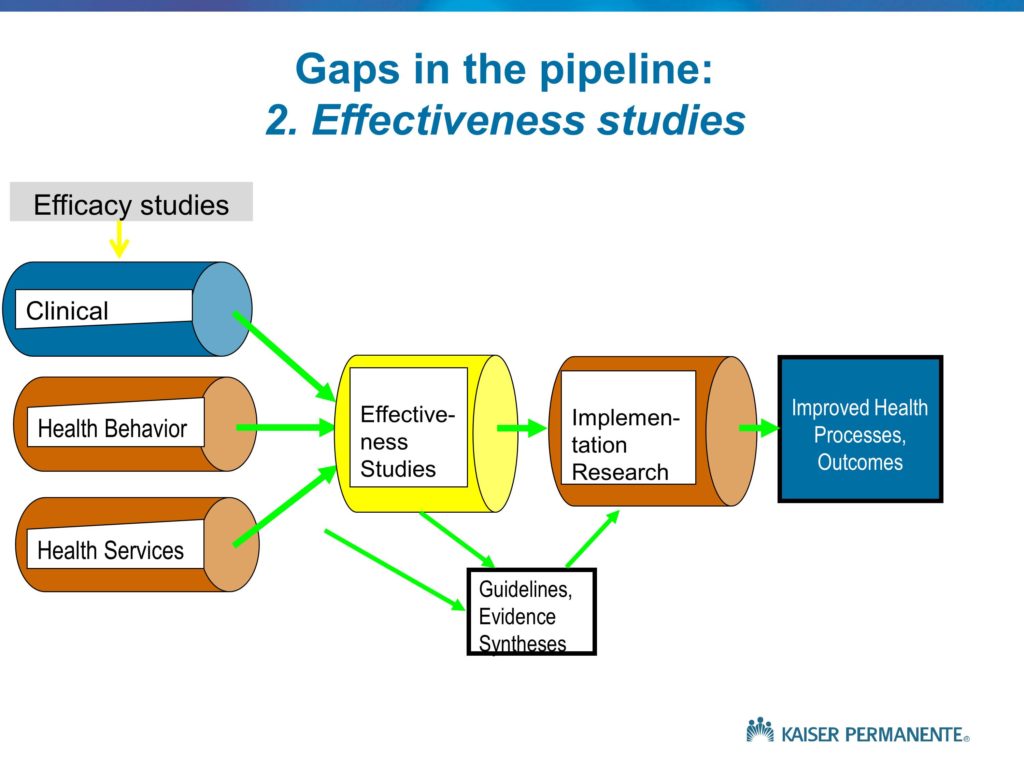

The next gap I’d like to talk about is one that I know Larry Green will address, and he and Russ Glasgow have written quite convincingly and eloquently about — and that is the distinction between clinical efficacy and clinical effectiveness studies. As implementation researchers, we will often lament the observation that the newest latest, greatest finding to be published is not greeted with extreme enthusiasm by the target clinicians whose behavior we hope to change. And they’re not quick to jump and change their practices immediately. Our conclusion is: What is wrong with these clinicians that they don’t recognize or subscribe to evidence-based practice? Why aren’t they adopting this finding? Well, they’ve been around long enough to know they just need to wait around another three months or six months and yet another definitive, groundbreaking study will come out that shows the opposite finding. And again, Larry will talk about this later on, but the bottom line is efficacy studies are not ready for prime time — the results of those studies. We need to wait until we see the effectiveness studies that tell us something about whether and how this practice operates under real-world circumstances.

We also, importantly, need to wait for the evidence syntheses or the evidence clinical practice guidelines that build on an entire body of research, in an attempt to synthesize the research and develop conclusions that tell us something with a level of confidence that we don’t typically have from individual studies.

There are many other arguments and many other reasons to focus on the effectiveness studies. In some fields within the medical research community, for example, there are studies that attempt to estimate the proportion of all patients that meet inclusion criteria in some of the so-called large, definitive clinical studies — numbers of 15% and 20% are not uncommon. Again, the practicing clinicians in some ways and many circumstances know a bit better than we do as academics that the so-called definitive findings are not necessarily definitive, but perhaps more importantly, they’re not necessarily relevant to their settings, their populations, and the kinds of real-world constraints and circumstances that they fit.

As an implementation researcher, we could argue that the problem is not with us, in our ability to develop effective implementation strategies — the problem is with the goods that we’re give. That the research results, the evidence-based practices, are not ready for implementation. That’s — as with many statements in this field — there is, of course, some truth to that. So, we can point the blame to those who precede us, but it’s not all their fault.

Let me move to the next gap in the pipeline. This begins to move into the realm of the implementation researchers and what it is that we do, or don’t do, that might contribute to the limited effectiveness and success of our implementation strategies. That is depicted by the middle segment of the pipe document and diagnose quality gaps. The patient safety folks have figured this out, and basically don’t proceed with a patient safety improvement strategy without conducting a root cause analysis. Most clinicians in medicine and other fields don’t proceed with a treatment before they’ve completed a diagnosis. Back in the 70s and 80s, and still far too often today in the quality improvement and implementation science fields, we jump immediately to the treatment phase without taking the time to conduct the proper documentation and diagnosis phase — to conduct the root cause analysis, to truly document or diagnose rather the causes of the quality gaps or the implementation gaps that we’re trying to close.

There is a Cochrane collaboration review group in the implementation science field that attempts to synthesize results of studies that evaluate specific implementation strategies. These include opinion leader strategies that involve a respected clinician trying to convince targeted clinicians to use a new practice; they include audit and feedback strategies that involve documentation of practices relative to the evidence-based guidelines in showing clinicians how often they follow or do not follow the guideline; implementation strategies that are synthesized by the Cochrane review group also include computerized reminders which in settings like VA and Kaiser involve a point-of-care reminder that reminds them of the appropriate evidence-based practice. Again, the Cochrane review group attempts to synthesize the relatively small but growing number of rigorous trials that evaluate those strategies. The typical finding of those syntheses, those meta-analyses, is very weak effects and high levels of heterogeneity. These strategies seem to work in some circumstances and for some problems, but not others.

The problem with that sort of approach and that way of thinking about implementation strategies as interventions is that it’s comparable in some sense to the idea that one would conduct a meta-analysis of the effects of aspirin for the treatment of headache and fever and HIVAIDS and diabetes and language disorders and a number of others. Those clinical treatments — those interventions are not meant to be cure-alls that are relevant to all problems. If we take the time to diagnose and identify the root causes of the quality gaps, of the implementation gaps, then we can sit down and think about an appropriate strategy, rather than going to some list of effective implementation strategies and pulling off the strategies that seem to have the highest pooled effect size. So that example, or that dimension of heterogeneity in the settings, in the problems, in the target clinicians — and the appropriate matching of a practice-change strategy to the characteristics of the problem is one we tend to ignore too often in the field of implementation science.

In this middle segment, the need to fully document and diagnose the quality gaps, before we move into the stage of proposing then evaluating an implementation strategy is one of the gaps in the pipeline that offer at least a partial explanation as to why it is that our implementation studies don’t lead to a significant, sustainable practice change. Again, the problem is not just those who feed us evidence-based practices and that they try to sell us efficacy findings, rather than effectiveness. The problem also lies in the way that we take those findings or innovations and attempt to implement them.

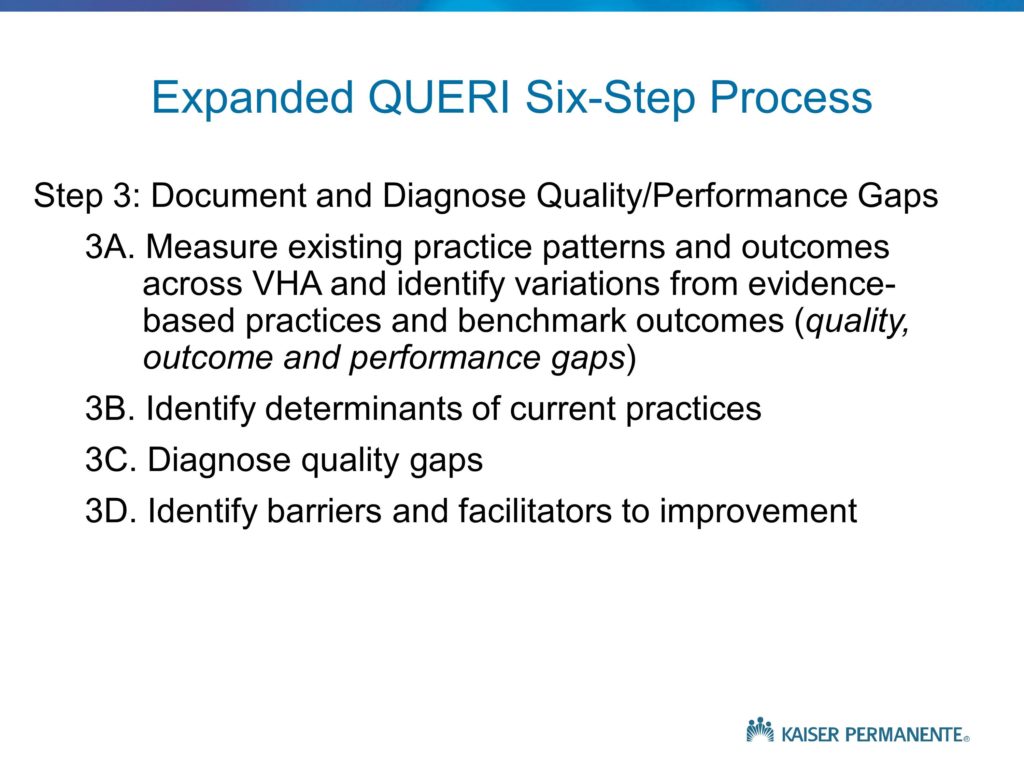

This is a part of a broader framework that is covered in one of the articles I will list, that talks about the specific steps we follow in the VA’s Quality Enhancement Research Initiative — the QUERI program. This focuses specifically on this middle segment in the previous slide. The individual steps in documenting and diagnosing quality gaps or implementation gaps or performance gaps. Again, in the interest of time I won’t go through this in detail, but as with many of the other frameworks it serves as a roadmap, in a sense, of the kinds of steps that are needed to fully understand and address quality problems and evaluate solutions to those quality and implementation problems.

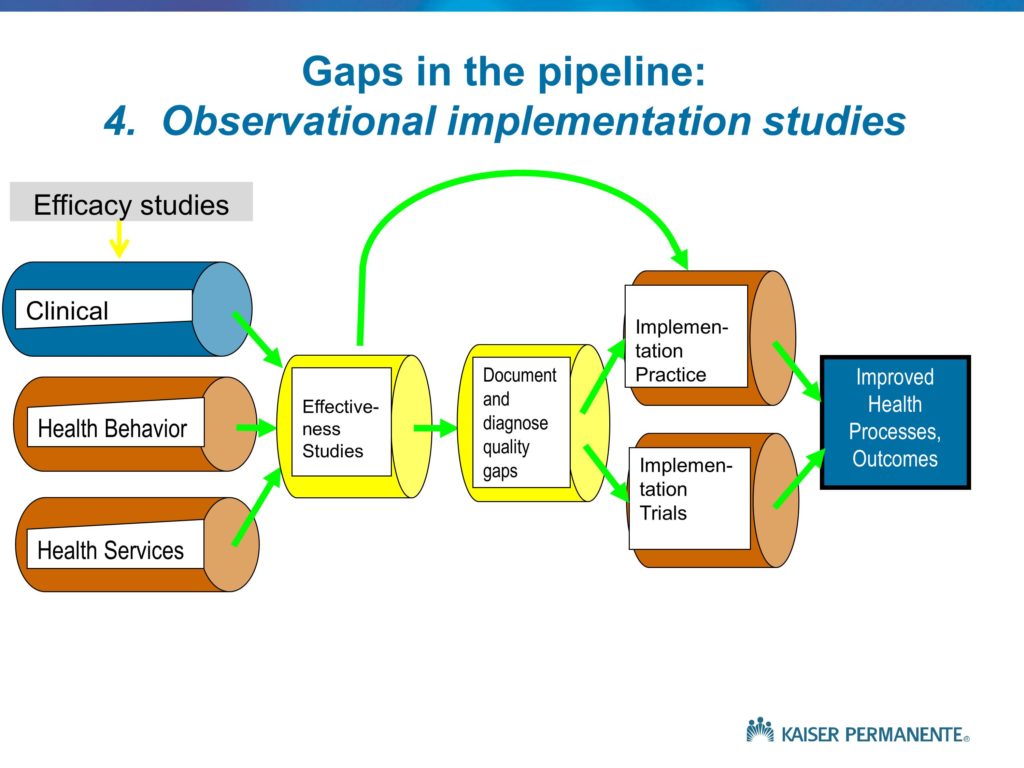

This diagram — and the looping arrow over the top is what’s new here — is meant to point out the fact that even though in many cases we do need to intensively and explicitly try to implement new practices, at the same time that we in the VA with Kaiser, for example, are working hard to design our implementation studies, submit grant applications, and wait for funding. Try to convince the sites that had agreed a year ago to participate that they should still participate, and doing everything we can to try to achieve successful practice change — at the same time that we’re going through that process, practice leaders and policy leaders back in Washington are implementing new programs within VA all the time. The number of insights that can be derived from those naturally occurring, or those policy and practice-led implementation efforts, are often much greater than the kinds of insights that we can — and often are not able to — derive from our experimental studies.

Dennis mentioned earlier, in response to one of the questions, the problem of grant reviewers not liking to fund the single case studies, the observational studies, and so on. One of the reasons that we don’t see more observational studies is not only the fact that reviewers don’t like to fund them, but researchers don’t like to conduct them. Everyone is interested in developing the latest, greatest effective strategy and evaluating strategy using the so-called gold standard RCT approach with an emphasis on internal validity, and showing a significant change.

The problem with these trials, and the experimental as opposed to the observational trials, is that they tend to be very artificial when they are researcher led. As researchers, we identify a set of priorities, and we attempt to convince our practice and policy colleagues to pursue those priorities which may not be theirs.

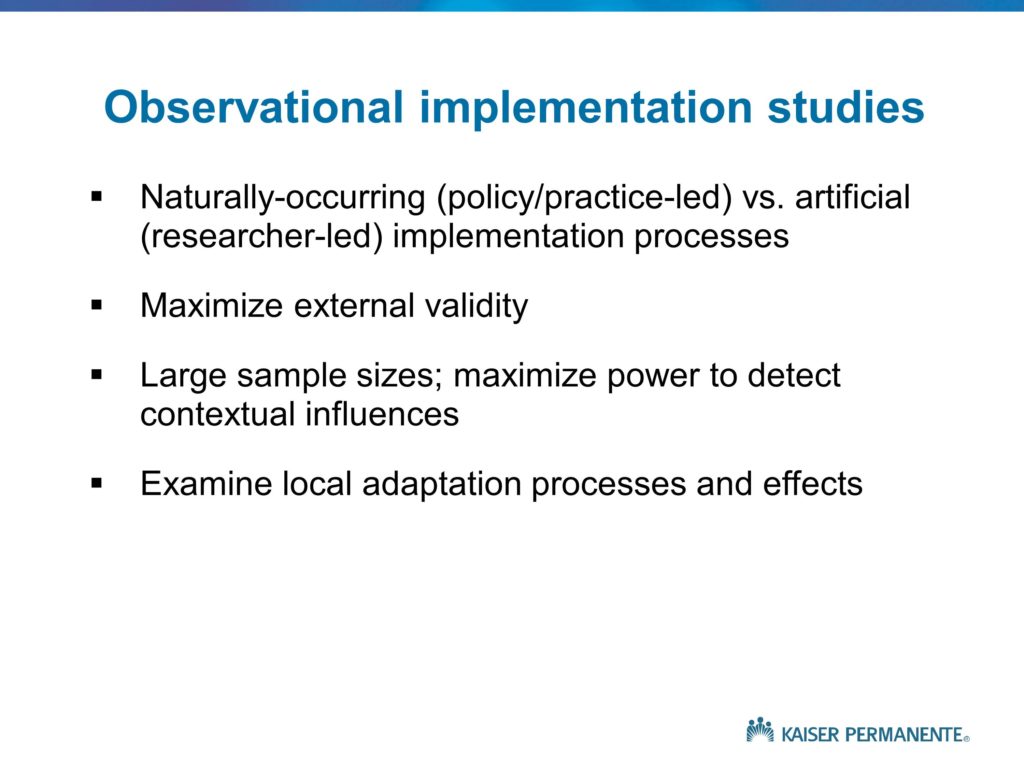

The observational studies maximize external validity, because they rely on the study of what naturally occurs, rather than what is occurring in a researcher-based-led manner. They allow us to use much larger sample sizes, and maximize our power to detect contextual influences. I talked earlier about heterogeneity. There is considerable heterogeneity across different clinics and hospitals in VA, across different schools, across different clinics within Kaiser.

If we have 10 or 12 key contextual factors that may include organizational culture, and size, and staffing composition, and leadership turnover, and budget sufficiency and stability and staff stability — by the time we get to a dozen of those, our ability to understand the influence of those contextual factors in a typical RCT, where we’re limited often times because of cost considerations to 20 or 30 sites, is quite limited. In the department of Veterans Affairs, with about 150 hospitals and close to 1,000 outpatient clinics, and with a good electronic data system, we have the ability to understand the effects of those contextual factors. Often times in the implementation world, the main effect of the practice change intervention is much weaker than the effect of the contextual factors.

There’s an extreme version of this argument that basically states that if we’re trying to change practice or improve quality in a medical setting, it actually doesn’t matter much which implementation strategy we use. What matters is the kind of leadership in place in the settings, what kind of staff expertise and commitment to the culture, and so on. Those contextual factors. That has some significant implications for power and study design, but again it points out the importance of contextual influences. To use a clinical parallel, it’s comparable to saying, if a patient presents to us with a given chronic disease, it actually doesn’t matter much which medication we decide to prescribe. What matters is the patient’s home environment, whether it’s stable, if they have a good job, supportive spouse, live in a neighborhood where they have access to good food and exercise and so on. It’s all of those other factors. Of course, in the clinical world, those other factors are important, but the main effect of the intervention, of the treatment itself, is important as well.

In the implementation world, often the effect of that treatment is relatively weak. And the observational approach allows us to understand those contextual factors. They also allow us to understand local adaptation processes and the effects of those. Pills can’t be modified. They come in a bottle, we can perhaps prescribe them in the morning or night, with or without orange juice. We can prescribe some supportive therapies. But we don’t have the ability to modify the composition of that pill. Implementation strategies, practice change strategies, can be modified. They are modified and adapted. They should be modified and adapted. And we should be studying how to guide that adaptation rather than ignoring it or attempting to achieve artificial fidelity to a program that doesn’t fit many of the settings in which we study it.

Again, the observational approaches allow us to study and understand those adaptation processes.

Let me go through just one final framework, then we should have about ten minutes or so for questions.

Although I’ve argued in many cases that we should prefer to study naturally occurring implementation processes using observational studies, there are instances where we do need to use an experimental or interventional approach. The lower right hand corner, for those of you who can see the wording, is an attempt to specify a sequence of experimental studies or trials that will allow us to make better progress in the implementation world. There are basically four phases. This is a framework that is based in part on the FDA four-phase framework for a drug trials, as well as the UK Medical Research Council framework for evaluating complex interventions. It draws in elements from both but is not precisely the same as both.

Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) Framework

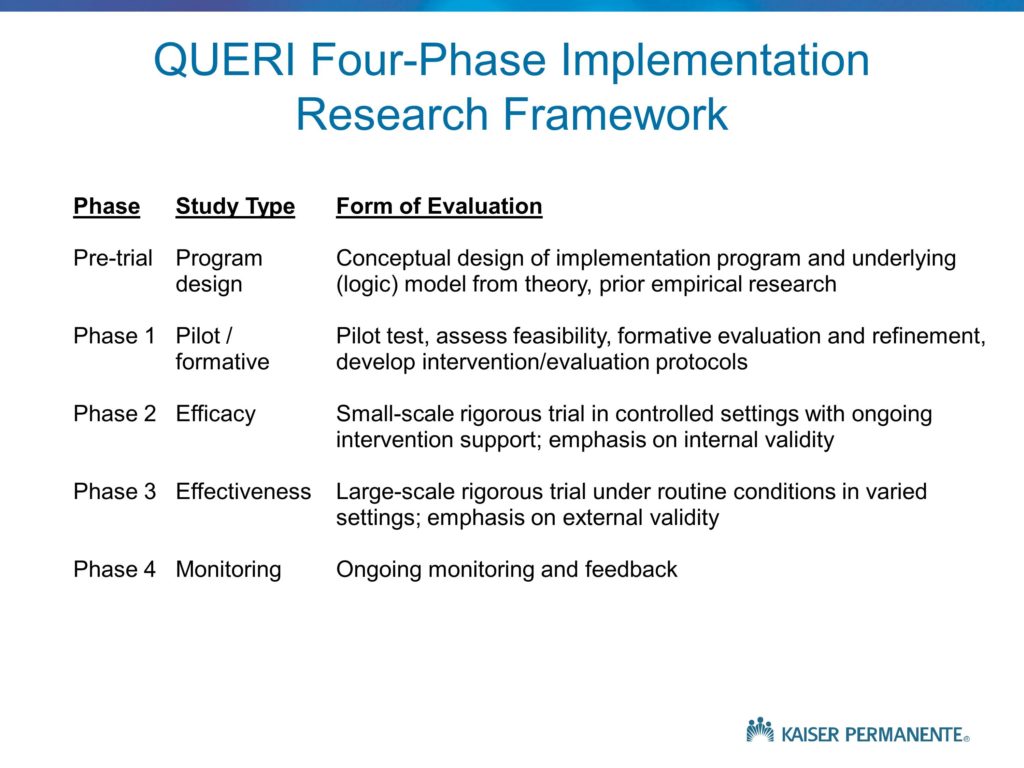

This, which is my last slide, is an attempt in words to describe the different phases. It points out, again, under Phase 1 the need for us to conduct the single site case studies. In the QUERI program, the Quality Enhancement Research Initiative, which we launched in 1998, there was great deal of pressure to show impact and show value very quickly.

As good medical researchers, we as QUERI researchers very quickly designed large, rigorous randomized trials of implementation strategies, and we very quickly learned large lessons as to why those implementation strategies were not likely to be effective. We discovered some barriers and some flaws in implementation and those practice change strategies very quickly. But these were trials. And in a trial you maintain fidelity, and you maintain fixed features of the study so you can show with high levels of internal validity the intervention-controlled differences. There was reluctance to allow for any of the modifications that, in many cases, were staring at us very clearly as to what was needed.

The single-site pilots — or two or three site pilots — allows us to very quickly learn those lessons very cheaply and quickly, in two to three months. The issue of funding within VA we have the advantage of core funds provided to the QUERI centers that allow them to fund these pilots internally without going through a six to twelve-month grant process. It may be, as was suggested, that’s a potential role for the Foundation. But again, we need to continue to work on NIH and NSF and our other funding agencies to point out to them that moving immediately to a three or a five year, $500,000, $5 million RCT without first doing the pilot funding is inappropriate and a waste of the research funds, as well as the time and effort of those sites that are participating.

We need to begin with those Phase 1 pilots. We then need to move into the efficacy-oriented small-scale trials that will tell us something about the likely or theoretical effectiveness of a given practice change strategy, under best-case circumstances. Which, in the case of implementation studies that are funded with grant support, often means high levels of study team involvement at the local sites in providing technical assistance and support, in exhorting the staff to keep with the program and follow the protocol, oftentimes the funds are used to support new staff and to provide for the training and supervision. Often we have Hawthorne effects due to the presence of the research team, and the measurement. As with any efficacy study, this is a method for evaluating whether, under best-case circumstances, a practice change strategy can be effective.

We often, in the implementation field, complete those studies, write them up, and essentially brag a bit about our success in improving quality. And then we walk away and go onto the next innovation, the next innovative practice change strategy. As is the case with the clinical studies that we use to develop new evidence and innovations, the efficacy oriented studies are not enough. We need to follow those with an effectiveness study, where the grant support does not provide additional resources, where the study team is not onsite on a weekly or monthly or daily basis. And where we have conditions of effectiveness research. We need to demonstrate in a much larger, more heterogeneous, more representative sample of settings and circumstances that this innovative practice change strategy can be effective. Then and only then can we turn over that practice change strategy, in the case of the VA, to VA headquarters. And encourage the national program office responsible for quality improvement, for example in HIVAIDS care, to deploy that program nationally. And at that point, as with any Phase 4 study, our role as researchers is to provide arms-length monitoring and help to observe how the program is proceeding, whether it warrants refinement, what are some of the areas where the program seems to be working better than others and why that is.

Again, another framework that serves to guide the design and conduct of an integrated portfolio of implementation studies. Before concluding, what I should say is these are idealized frameworks, many of them in fact are not completely feasible because the number of years it would take us to go through each of these is beyond what we should be spending. I mentioned but didn’t talk about hybrid studies that combine elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research. There are also hybrid studies that combine elements of pilots in Phase 1 or Phase 1 and Phase 2. These are also very linear, rational kinds of frameworks that don’t necessarily describe the way the world works as much as the way that in some sense we might like the world to work. I won’t spend any time trying to talk about how it actually does, I know that will be covered to some extent in the subsequent presentations. It also is an area that needs more activity and research and contributions from all of you.

Again this is to provide an answer to some of the key questions what is implementation science, how does it differ from other forms of research, and how do we go about thinking about the design and conduct of a portfolio of implementation studies. With that, let me stop and open for any questions.

Questions and Discussion

Audience Question

We know a lot about the basic physiology of speech production, and we are developing a lot of strategies to help people sound better. It’s that implementation part: We get them sounding good in treatment and say, “Go out and communicate well.” We know so little about how people with communication disorders function in the real world. You used the term root cause analysis — Would you talk a little bit more about what you mean by root cause analysis and how we might implement that in our situation?

A couple of thoughts. One is that, if I’m understanding you correctly, I would characterize the issues and the problems you’re describing as within the domain of the clinical research, rather than the implementation research. If we talk about the effectiveness or lack of effectiveness of the clinical strategies that are used to support the clients, the patients, and to achieve better performance on their part, and those don’t have lasting effects. I would see that as a flaw in what I’ve labeled the clinical intervention.

There probably is a role for root cause analysis in trying to understand what it is about those clinical treatments that don’t allow them to have sustained effects. But the implementation research would focus on the goal of trying to ensure that the therapists are delivering those effective clinical strategies. Root cause analysis in the implementation world is all about what is it about the therapists training or their attitudes toward evidence-based practice, or the kinds of constraints that they deal with in their daily worklives. Lack of time, lack of support, lack of skill, to prevent them from delivering those therapies with fidelity. It does sound to me like the problem here is in the limited effectiveness of the clinical treatments.

Audience Comment:

Let me just give you an example. I really do think it’s in the implementation. We talk to a lot of people about what did you like and not like about our treatment they say, “I was discharged at X amount of time because my funding ran out.” When you go to clinicians, “I stopped treatment not because it was not needed, but it was because I didn’t have the funding.” That’s not a part of our treatment, that’s a part of the implementation policy.

Brian Mittman:

Sure, you’re right. And in some ways, a combination. Because the treatment that is efficacious under best case circumstances, but is unfeasible is not likely to be effective. And the effectiveness or lack thereof, limited effectiveness, is a combination of some features of the treatment that are not scalable, as well as some features of the implementation process and the broader context that doesn’t allow the clinicians to provide the proper training and use the treatment in the way it was designed and intended to be used. Again, I think the root cause analysis, to get back to your original question, is appropriate for both of those. It is a matter of understanding, is it a matter of comfort on the part of the therapist, is it a matter of the regulatory or fiscal policies not being supportive? Do we lack the kind of equipment that we need? And so on and so forth. Those are the kinds of potential causes for poor fidelity and poor implementation that we need to understand.

Much of the early work in the implementation field in medicine focused on better strategies to doing medical education. That assumes that the problem is education. Often times clinicians know exactly what to do. They don’t have the time, they don’t have the staff support. Patients are resistant. There are a number of other barriers. No amount of continuing education will overcome those barriers, so we’re solving the wrong problem. That’s where the root cause analysis or the diagnostic work is all about identifying the causes so we can appropriately target the solutions.

Audience Comment:

And the methods are interviews? Or going out to stake holders?

Brian Mittman:

Keep going.

Audience Comment:

Or looking at databases?

Brian Mittman:

Keep going. Yes. All of the above.

Audience Question

Could you say a little bit more about the blurriness, or trying to handle the blurriness, around establishing efficacy? Do you really need to have established efficacy before you’re going to study implementation? And how can we contend with not having that be unidirectional — but that the implementation affects the efficacy. I may be pushing you to talk a little bit about the hybrid models.

I think the hybrids relate to both of the previous two questions. One of the papers I will circulate lays out the hybrid concepts. The idea is that this linear process would take far too long. We often have enough evidence that something is likely to be effective. And we also have enough concern about the effectiveness, depending on the implementation strategy, that we really need to do both at once. So there are instances where, first of all, where we are conducting an effectiveness study and we begin to collect implementation-related data. If we are evaluating an innovative treatment in a large, diverse, representative sample of sites without providing the kinds of extra fidelity support that we do in an efficacy study, that’s our best opportunity to begin to understand something about the acceptance and likely use, and barriers to appropriate use of that clinical treatment. So we begin to gather implementation-related data.

But when we are focusing on the implementation strategy, we need to continue to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and the clinical outcomes. If we have a truly evidence-based practice, and we know from a large body of literature that delivering that practice will lead to better outcomes, we can focus only on implementation. We know that if we achieve increased utilization of that practice, those beneficial health outcomes will follow.

But oftentimes that evidence base for the clinical questions is not sufficiently well-established. There are interaction effects between clinical efficacy and effectiveness and implementation and fidelity, and we need to be doing both simultaneously. That’s what the hybrid frameworks are all about. Studying the success and effectiveness of a practice change strategy to increase adoption, to increase fidelity, and continuing to measure clinical effectiveness so that we can determine whether we see the benefits as this practice is deployed in real circumstances, with different types of implementation support or practice change strategies.

So, our work on the clinical effectiveness side never ends. And again, distinguishing between these different aims and understanding their implications for sampling and measurement and analysis and so on is one of the key challenges, and one of the goals of the paper I was involved in drafting with some VA colleagues.

Audience Question

We’ve been using a program for about 14 years, adopted from Australia, called the Lidcombe program. There are many studies by the group in Australia and ourselves as well showing that it’s efficacious. Now it’s important for us to move into the effectiveness domain. But after reading Everett Rogers, I’m highly aware that the context is really important, that the culture is really important. I wondered if you had any tips about how to assess the resistance, because there is a lot of resistance, particularly in the United States, to this program. I’m thinking okay, this is a cultural issue. Is it the culture of the speech-language pathologists who are working with pre-schoolers that has been influenced by some of the belief that you shouldn’t talk about stuttering to a pre-schooler? Or is it a problem of the setting? In other words is it not easy for the SLPs to make it work in their setting? Do you have any tips?

Again, I think the answer is probably all of the above, but if you recall the QUERI step 3 slide, where I showed the distinct steps in the diagnostic process, one of those steps is a pre-implementation assessment of barriers and facilitators, and the idea that we spend some time using the methods that were mentioned — interviews and observation and so on — to try to understand and make some educated guesses as to the response to an effort to implement this therapeutic approach, and to identify some of the key barriers and see what we can do to overcome them. But ultimately, we won’t identify those barriers until we actually get out and begin to implement the program. Was it Kurt Lewin who talked about the need to attempt to behavior as a way of understanding barriers, rather than in an a priori manner, assuming we can correctly project them.

There are some other frameworks in the field that focus on the multi-level nature of influences, barriers, constraints to practice change, and talk about the different kinds of strategies that would be needed to address the individual clinician factors, the setting factors, the broader social-cultural, regulatory, and economic factors. Typically the answer to the question, “What is impeding implementation?” is: All of the above. It’s all of these factors.

And our implementation studies only tend to focus on one or two. If we only focus on education and knowledge, again, we’re doing nothing about that broader spectrum of factors. The answer to the question is, the barriers and the influences occur pretty much everywhere we look. It’s a much more complicated set of problems, and we need to be thinking about and using another set of frameworks within the implementation science field in health that identify contextual factors, beginning from the regulatory and broadly social-cultural, all the way down to the front line delivery point-of-care factors. And think about all of those as potential barriers to practice change, as well as potential targets for our implementation efforts and our practice change efforts.

Audience Question

The rapid and frequent changes in terms of healthcare reimbursement has caused me havoc in terms of my treatment efficacy research. For example, right now I have a person with severe apraxia of speech who is turning 65 in a month. As soon as she turns 65 there is a serious effects of the therapy cap and that sort of thing. Well, we’re changing our treatment to do more functional communication, but what I really want to do is continue my study to see whether this treatment I’ve devised is going to help her with effective communication. So, I know you can’t solve that problem, but I want to bring it up as an issue for discussion. I’m anxious to hear more about the hybrid studies, and any advice people can give us when we have to interrupt our nicely designed single-subject designs in the middle to meet the patient’s real needs, related to reimbursement.

I can offer one quick response, then I know Dennis, I’m sure, has more to add. My response is we need to be thinking about doing both. By both I mean trying to develop and evaluate therapeutic approaches that we believe will be effective and feasible given the current socio-economic, regulatory environment. But at the same time developing therapeutic approaches and studying and evaluating them even though we know that right now they’re not likely to be feasible, sustainable, scalable.

The reason is when we demonstrate significantly greater effectiveness, that’s the evidence that we need to lobby for the changes. I think the important thing is to recognize from day one — there’s an important concept in the field, and someone may talk about it later, of designing for dissemination. It probably should be designed for implementation, but that doesn’t sound quite as good. Thinking from the very beginning about designing for feasibility — but we shouldn’t limit ourselves to the kinds of approaches that are likely to be feasible. We need to be more innovative at the same time.

Dennis Embry:

One of the things that came to mind is, one, I think it’s really important to do the eco-anthropological type of investigation before we go do one of these things. Because one of the things you find out is all these little stupid barriers.

I loved your idea about looking at the regulations. I think concurrently going to the end point and observing a whole bunch of people just having that therapeutic interaction tells you a whole lot about what are the contingencies. I’m reminded, early on in behavioral analysis people talked about doing an eco-behavioral assessment before you actually designed an intervention to pull out some of these pieces.

The other thing I think is often forgotten is Trevor Stokes’ paper and Don Baer’s paper on the technology of generalization. And so many people don’t think about the generalization features in the design of their study. Your presentation convinced me that the thing I decided to start doing a long time ago was, whenever I’m in a Phase 1, just run it as a mini-effectiveness trial rather than an efficacy trial because, if I do the efficacy thing and it works, but it won’t work in the real world it’s kind of dead. It might be a good thing for a publication but — I’m learning we have to think about the effectiveness right off the bat.

Brian Mittman:

And I think that is the key point to think about these issues. There aren’t necessarily right or wrong answers, but to be aware of whether you are studying clinical effectiveness or implementation or both. Understanding whether it is an efficacy or effectiveness study. And thinking down the line, what is the next step? What follows this study It’s not enough for us to complete our work, publish it, and say, my job is done, someone else will come along. That’s what leads to these roadblocks and these long delays in progress. That’s what leads to the criticism that too much research is beneficial for the academic’s careers, but doesn’t have much value or benefit for society and that’s not why we’re here.

Audience Question

I really love the sort of diagnostic paradigm you’re putting on this problem, and it makes me feel like this is our business. We are supposed to be doing diagnostic root cause analyses before we do our clinical interventions, and we need to do that here, as well, in research. I work in the area of swallowing disorders and one of the interventions that’s attracting a lot of attention is the idea that people need to clean patients’ mouths to deal with bacteria formation. If you go to the literature there are, first of all, arguments about who is supposed to be cleaning people’s mouths — but it’s really the most depressing literature I’ve ever discovered about how hopeless in-service education is. I’m just wondering whether you have a provocative paradigm shift to offer about in-service education because I think we’re sort of perpetuating the same problem.

To me the phrase that captures this concept is, “necessary but not sufficient conditions.” The education is almost always necessary, but it is not sufficient. Thinking about necessary but not sufficient conditions for practice change, and thinking about multi-level, multi-component kinds of practice change interventions and programs. I actually, in addition to my dislike of the T-work, I dislike the I-word for practice change. These are not interventions, these are implementation programs or campaigns that are multi-faceted, they have multi-components, and the clinical intervention is what we try to implement using an implementation strategy or program or campaign. The needs include multiple elements that we sometimes mix and match –sometimes within a single study at different sites. Because in some cases this is a leadership problem or a culture problem, and in other settings there is not. It makes for a very complicated but very interesting set of challenges. We need to acknowledge, rather than ignore and hope that through the magic of randomization all these factors will disappear.

The main effect of any given component of an intervention — education and others — is very, very weak. And without combining a set of intervention components within a campaign or program, we’re not likely to see any practice change, let alone sustainable, widespread practice change.

References

Bero, L. A., Grilli, R., Grimshaw, J. M., Harvey, E., Oxman, A. D. & Thomson, M. A. (1998). Closing the gap between research and practice: An overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. BMJ, 317(7156), 465–468 [Article] [PubMed]

Curran, G. M., Bauer, M., Mittman, B., Pyne, J. M. & Stetler, C. (2012). Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact.Medical Care, 50(3), 217 [Article] [PubMed]

Eccles, M. P. & Mittman, B. S. (2006). Welcome to Implementation Science.Implement Sci, 1(1), 1–3 [Article]

Stokes, T. F. & Baer, D. M. (1977). An implicit technology of generalization.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 10(2), 349 [Article] [PubMed]

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2015). Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI). Veterans Affairs | Veterans Health Administration(Available from the VA Website at www.va.gov).