Highlighting issues and research related to disseminating scientific evidence in a shared decision making paradigm

The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

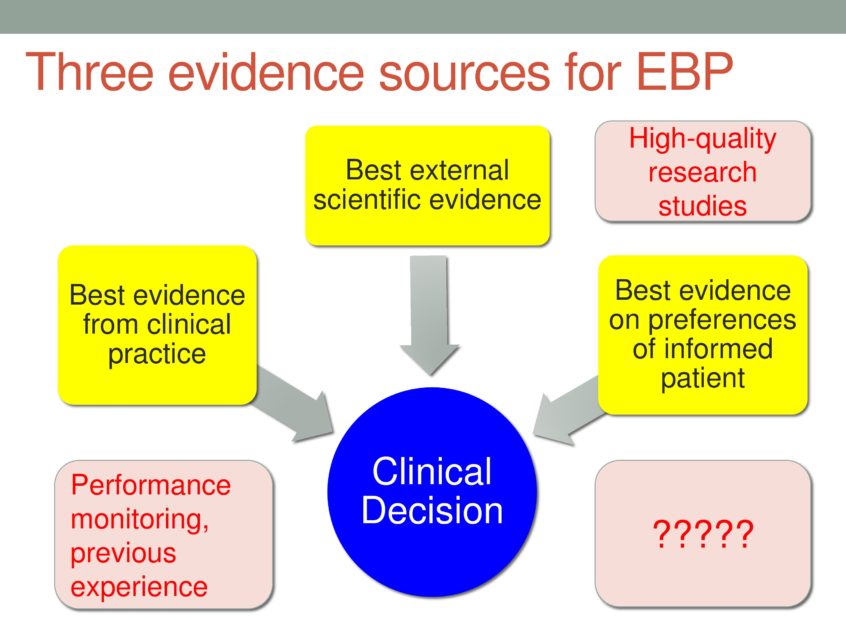

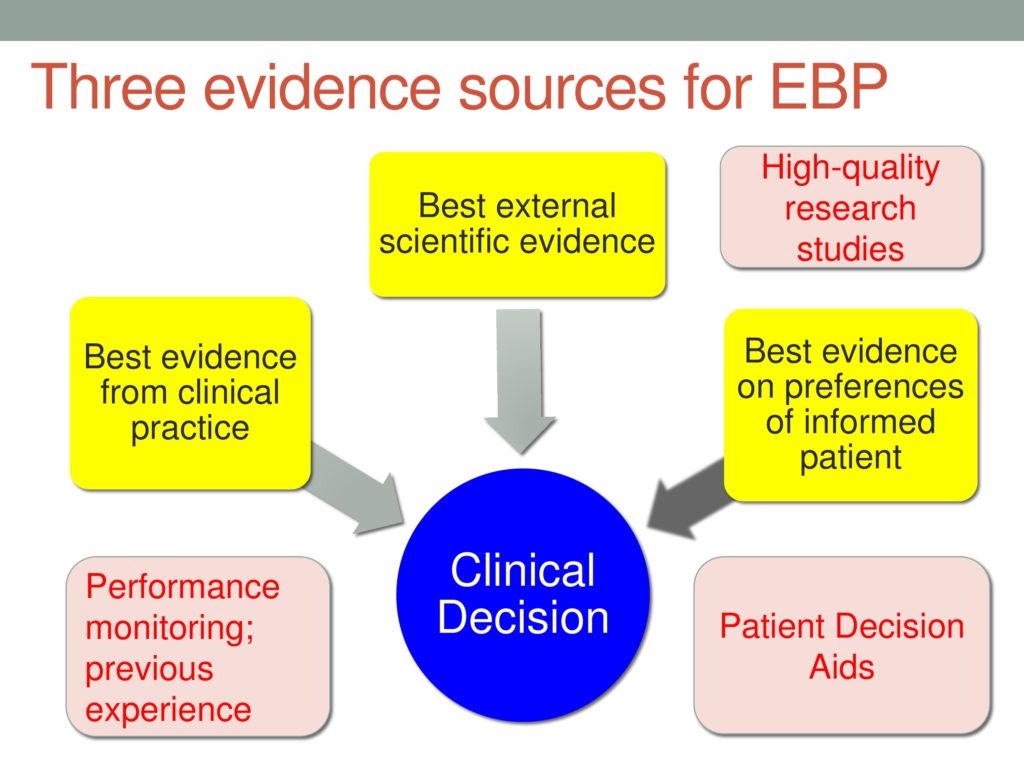

I’d like to start by putting this in context a little bit, and that is the way I started thinking about evidence-based practice is that we really have three kinds of evidence that we need to be trying to integrate when making a clinical decision. At the top — not because it’s most important but because it’s most often talked about — we have the best evidence from scientific research, and on the left, we have best evidence from clinical practice, and then on the right we have best evidence on the preferences of an informed patient. And all of those are going to feed into a clinical decision that has to be made in the context of uncertainty.

The question is where do all these different kinds of evidences come from? When we talk about best external scientific evidence, we know that we can look at high-quality research studies for input into that level of evidence. When we talk about best evidence from within clinical practice, we can talk about routine performance monitoring, the kind of daily record keeping that you keep track of with your patient about how their performance is improving or not improving. What the rate is and so forth, as well as, I think another source of evidence for this component of this second E in the EBP model is your own previous experience. Consciously or not, you are keeping track in your head of the patient you have seen that are similar to the one you’re working with, and that source of internal clinical evidence is also part of the actual definition of evidence-based practice. So it’s important to acknowledge that we’re not just talking about the external scientific evidence. And then on the far right — we kind of talked about those two Es in the three-E BP model, but how do we get evidence about the preferences of an informed patient? Where do we go for that?

We haven’t seen much attention paid to that in our literature, but there’s a whole literature on these things called patient decision aids in other fields that I’ve been really interested in. It’s been fun to take a look at how other clinical professions are approaching the need for this kind of evidence, and so my goal today is to acquaint you with some of the approaches, some of the literature, some of the evidence on the use of patient decision aids.

PDAs as they’re called, have been defined as tools that are meant to help patients participate in decision-making about their care, and they really help patients in two ways. Remember that I said that we like to know, and we like evidence on preferences of an informed patient, right? All of us can express preferences without a lot of information about what we’re talking about. Sometimes I think that’s what’s happening in a lot of political debate these days. People have strong feelings without a lot of content behind them, and so when we want patients to be involved with making decisions about their care, we need to take seriously the idea that they need to be informed about their options and informed about their condition and informed about the pros and cons of the different options that are available to them. So that’s one of the ways that PDAs are supposed to help patients participate.

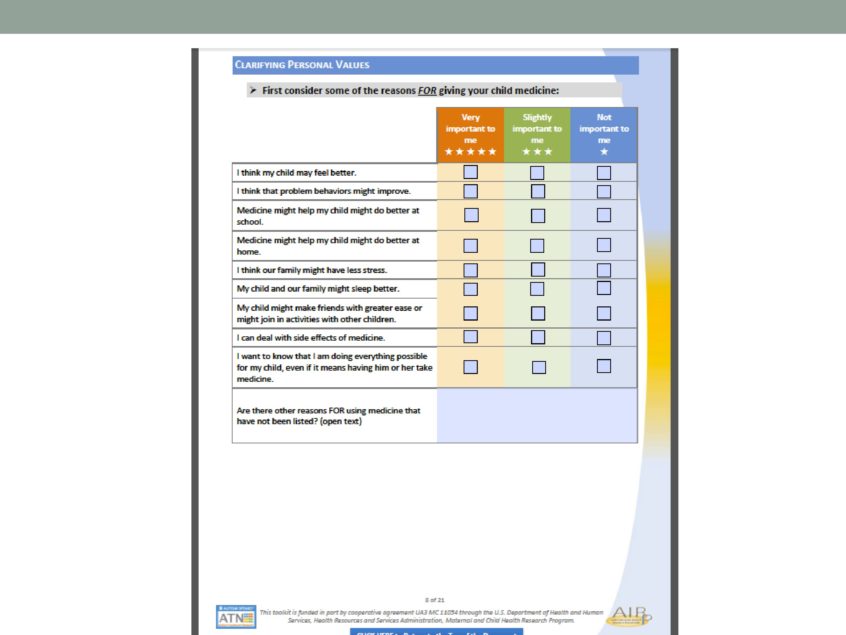

The other is that PDAs really include a specific values in explicit values clarification process in which the idea is there is a very systematic and organized framework for having patients consider each one of these possible, reasonable clinical options, the pros and the cons of each of these options, and then explicitly think about how much does that possible advantage matter to me and actually do a rating with a little five-star kind of icon to judge, okay, yeah, it’s important that I do this, but it’s maybe worth the two stars as opposed to, okay, for this possible advantage, that’s crucial for me, I rate that a five-star approach.

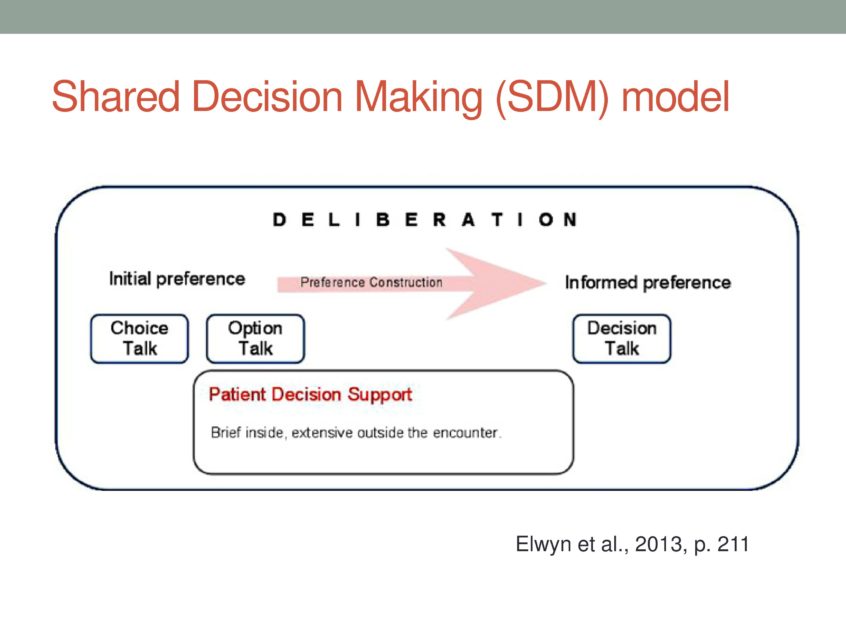

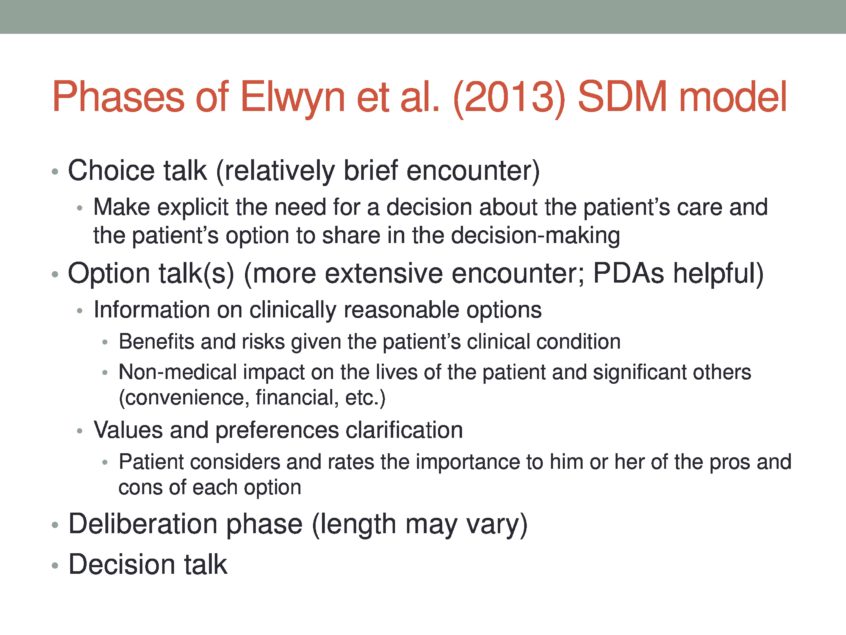

The shared decision-making model of clinical practice is kind of interesting, and I like the little graphic. So this is from interesting work by Elwin and her colleagues. I like the graphic because the idea is that using a PDA and helping patients participate in their decision-making is really a process that involves several stages, and she graphs it here showing there’s an initial preference. Then there is preference construction during the period of deliberation for the patient, and then finally, an informed preference that can be made. She breaks it up into choice talk, option talk, and decision talk.

The idea with these different phases, the choice talk is really a relatively brief encounter, in which the patient is made aware what exactly is the choice that I have facing me? What are the options? Even knowing that I have a choice in what’s going to be my recommended next steps for care, many times, at least in my professional experience, we don’t actually share that with patients. I mean, I think a lot of times, we get our graduate degrees, and we think that our job is to be the expert and make the best choice and simply tell our patient, “Here’s what you should do.” And certainly, there are some people facing healthcare decisions, you can think of your own medical care, for example, with your physician, where you know it’s complicated, and you honestly, sometimes, when you face a lot of stress you just feel like, “Just tell me what to do. What would you do if you are in my shoes?” And that’s just fine as long as you know that you have the choice to be more involved if you wanted to be. So this choice talk is step one.

The second phase can take more time, and this is where the actual options are laid out for the people who are actually interested in participating in making the choice. We’ll talk more about all these things, the information in the values clarification phases, those two pieces of a PDA.

Then the deliberation phase where the patient has the information and can mull it over, and then finally, the talk with you about the decision that they’ve reached. And there’s certainty about the decision.

So why? Now we know what PDAs are. Why are they? The origins of this PDA concept lie in the fact that in medicine, in Com D, in most clinical fields, there’s no single, clear best option for clinical care, for what should be done next, either in terms of diagnosis, screening, whether to proceed with treatment, what kind of treatment. There’s usually not a single head and shoulders best alternative, and so there are reasonable options that face all of us with these decisions, and when that happens, different people have different opinions and feelings and values, Certain aspects of one approach over another, and so these patient decision aids are really an explicit acknowledgment of that, an attempt to match the features of the options to find the one that best matches the values and preferences of the patient.

So there’s some evidence on PDAs, a growing body of evidence. That’s an iceberg. First I didn’t have the parentheses, tip of the iceberg. I just had an iceberg, and I thought maybe that’s not the best metaphor for patient decision aids because it might look like the Titanic heading in that direction, which is not my intent.

So this is just a smattering of some of the evidence, and there are quite a few individual, randomized, controlled trials, randomized clinical trials of using PDAs versus not using them, and in a variety of areas, so just to give you an idea. There are some ones that are at least tangentially related for many of us to our field. You see them listed there. Prenatal screening for Down syndrome, ADHD, temporal lobe epilepsy surgery, and surgery for breast cancer.

In addition to those individual studies, there are several systematic reviews and meta-analyses and most recently, in 2011, Stacey and colleagues published a Cochrane review, a meta-analysis of PDAs in the Cochrane Review, which is sort of the gold standard, and they were able to identify and have 86 studies meet their eligibility criteria, and so these studies involve more than 20,000 patients, which is a nice sample size, of course, to address a particular question. Not all 20,000 of those people were available to address each aspect of PDA use, and they compared PDA to TAU or treatment as usual, as it’s sometimes called or BAU, business as usual as it’s sometimes called. We need a better acronym for that.

In a nutshell, the Stacey et al meta-analysis findings showed that PDAs, there was strong evidence that they were effective in the ways that probably are the most believable, most plausible. That is, patients who work through PDAs are better informed about their condition and about their clinical options. Patients report and practitioners both report that their communication has improved by the use of the PDA just because things are stated explicitly and acknowledged that there is a deliberation process and they increase the proportion of patients who are actively involved in their clinical decisions and not surprisingly, when you have buy in and you’re part of making a decision, you’re usually more invested in more satisfied with the decision than if it’s imposed on someone from outside, right? These all make sense? Patients end up after PDAs feeling less decisional conflict that what’s meant there is just feeling like you weren’t really sure about what you should’ve done. You didn’t really feel like you had enough information and are not clear that the decision would align with your values and preferences, and it also made – fewer patients were undecided.

Okay, on the other side of the balance sheet, okay, in terms of what we know at the present about PDAs is that there’s no evidence that they reduced patient anxiety, improved overall health outcomes, or specific health outcomes, but they weren’t able to have enough power, enough samples, enough subjects to really test specific health problems and determine whether or not the PDAs improved specific health outcomes. So I’m making an excuse for it, because I really hope it’s true that it’ll be true. I’m showing my bias here, but the state of the literature now does not support that conclusion.

If you think that some of our patients are not complying with our recommendations. That’s called adherence in the medical literature, of course. It would be nice to be able to tell you that there’s evidence that patients who participated in their decision-making adhere to the subsequent decision more closely than patients who weren’t involved, but on that kind of question, there’s simply insufficient evidence to even make a determination at this point. So there aren’t many studies that actually address that. No are there enough studies to talk about the impact of using PDAs on health care resource utilization, for example. There’s certainly some evidence that patients who are given PDAs, when they face major surgical treatments and invasive procedures, tend to select less invasive treatment options for, say, prostate surgery. I’m sorry, that’s a screening one. For breast cancer treatment and for screening, they tend to opt not to have the PSA screening for prostate cancer when they’re informed about the choice that they’re making, but we don’t have enough evidence yet to judge whether that’s going to be a noticeable reduction in costs of clinical care just by using a PDA.

And the last one is very interesting. They found that the length of the consultation or the length of time that the clinical interactions varied according to PDAs being used or not used range from shorter time with PDAs, eight minutes less, up to 23 minutes more with a median of 2.5 minutes more for use of a PDA, okay? So what you think about how could it be less using a PDA? How could you spend less time than you normally would consulting with the patient? Can you imagine how that could happen?

Yeah, so if you have to talk through all the possibilities, and, you know, have the speech-specific question be raised by the patient, and you might think of something else, as opposed to having this really organized, systematic framework, that’s my hypothesis. The meta-analysis wasn’t able to tell us what the actual reason was. If we were highly motivated, we could go read the studies and find out if that’s what the authors thought too, but think it’s plausible.

So evidence on PDAs. It looks like patient decision aids have some advantages, but it looks like they require a little more time. So now you face a decision, right? Should I consider using these things? So this is a really good opportunity for me to show you what they look like.

So there’s the ideal site for learning about PDAs, is run by the Ottawa Hospital research Institute or OHRI, and I can’t say enough good things about this website. It has a wealth of freely downloadable forms.

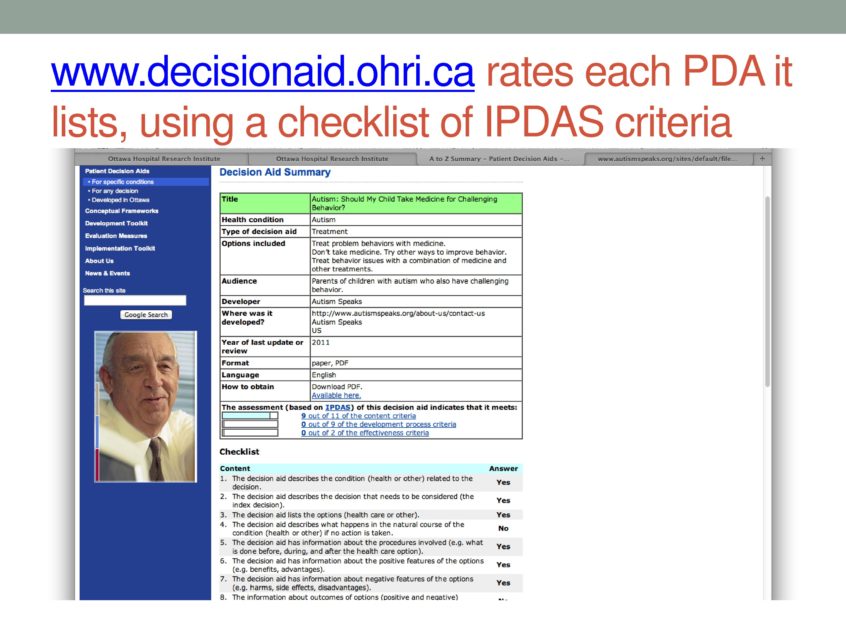

There are video tutorials of talking with a person who faces a decision at each step of the way, and there’s a huge searchable database of PDAs that have been developed by various organizations on different healthcare conditions. So you can search for a particular condition or you can browse alphabetically, et cetera, and then for each one of the PDAs that appears on their inventory, there’s a link to the actual PDA, as well as this group evaluates each PDA according to the standards that have been created by a group called by the international IPDAS, International Patient Decision Aids Standards group or consortium or something like that.

So look their first, I would suggest to you, if you’re interested for models and so forth, and I’m going to pull, I’m going to show you one, and the one we’re going to start with this called the Personal Decision Guide. So this isn’t specific to an individual healthcare decision. This is for any tough decision that anybody faces at any point in their life. So just think for a minute about some decision you’re facing, all right? That’ll be a little context here. Do you have to make a decision about something in your life at the moment? Do you have one in mind? It’s good if you do.

All right, so now, with that decision in mind, let’s look at what the forms look like, and I’ll also point out, is my slide does, there’s also a family decision guide, when there are multiple people that need to have input into a decision. So that’s another form that you can get there. We’re not going to look at it today.

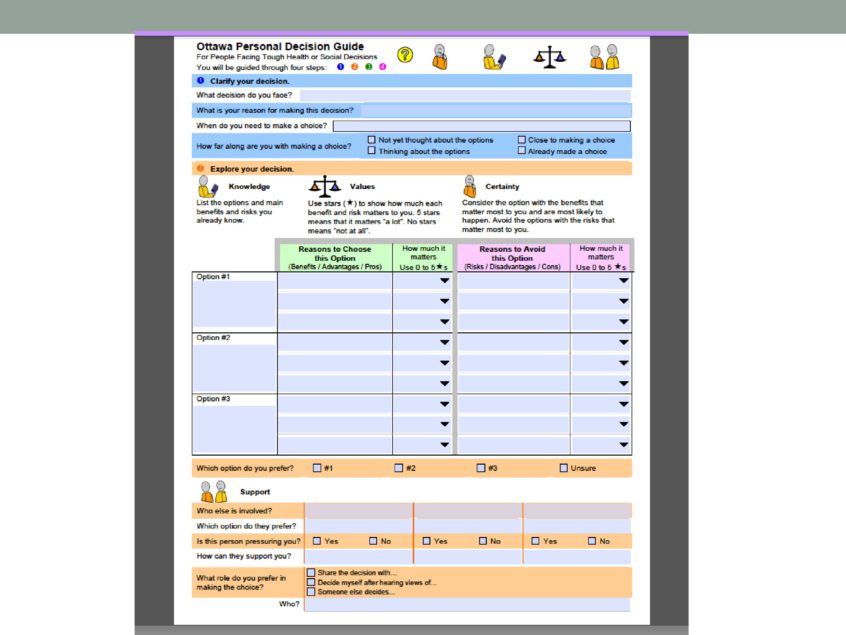

Here’s page one of the personal decision guide, and the first thing is to say what decision do you face? Second, what’s your reason for making a decision, just internally: Use your mental speech, inner speech, to think about the decision you’ve thought of. When do you need to make a choice? How urgently does this decision need to be made? How far along are you with making a choice? Have you not yet thought about the options? Are you thinking about the options? Are you close to making a choice or have you already made a choice?

Then explore your decision. This is where the knowledge pieces come in and the values clarification pieces come in. So, I face a choice my life, and as I see it, there are three things I can do at this point. There are three options that I have. So option one might be whatever it is, and then you see there are what would be my reason for choosing this option? What would be good about that, and then the star rating? How important is each one of those possible advantages of option one to me?

Then on the pink side of the graph is reasons to avoid this option, and again, how important each of the potential risks or harms or costs are to you with the star rating scheme? At that point, you’re ready to say which option are you leaning towards, having looked at your stars. Even just doing this part can be really clarifying when you actually take the time to be explicit about what you see as pros and cons, and how much you care about each one of them.

Toward the bottom, then that’s a section that asks you to consider what additional support you need, or who else needs to be involved in this decision? What’s their preference? If they’re going to play some role. Is this person pressuring you? How can they support you, and finally, what role do you prefer in making the decision. I’d like to share the decision with somebody. I’d like to decide by myself after hearing views of somebody else. Or I’d rather have somebody else side.

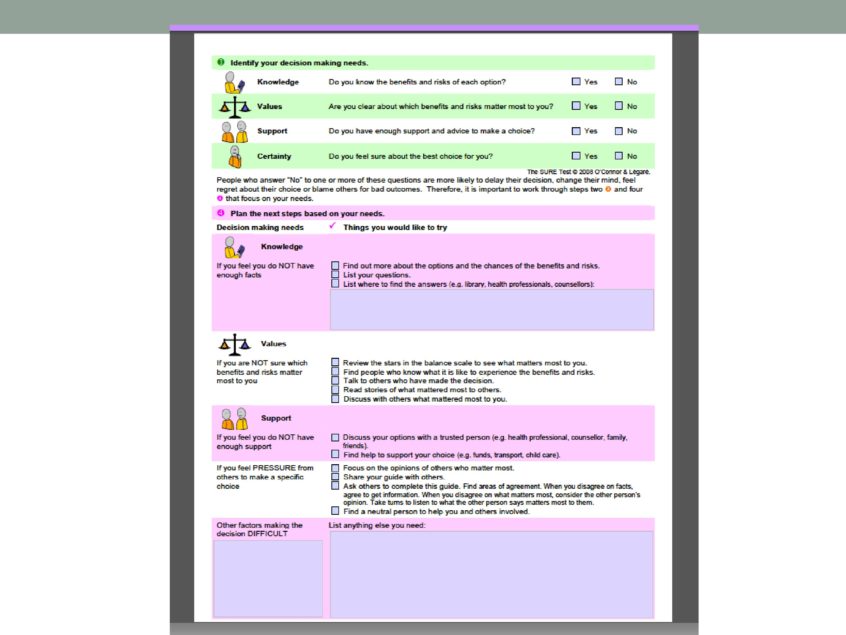

Okay, then at this point, in the personal decision guide, the idea is to say, okay, what additional information do you need to make the decision? So do you know the benefits and risks of each option? So explicitly, do you understand those two components? Are you clear about which ones matter the most to you? This is talking about the values clarification piece. Do you have enough support and advice to make a choice at this point? If aclinician is talking with somebody, talking it through a somebody, that’s an explicit way for the patient to discuss with you or for you to say, “I see that you feel like you’re not really sure about this. Let’s talk about that some more or let’s clarify that area, okay? And then certainty. How certain are you?

And then planning next steps, right? Things you would like to try. If you feel like you don’t have enough facts, I’d like to find out more. I’d like to list my questions. I’d like you to tell me where to find the information. For values, if you’re not sure which benefits and risks matter most to you, okay, here are the choices. Review the stars. Find people who know what it is like to choose each option and talk to them. Sometimes, with big decisions, it’s good to know people. So that’s explicit acknowledgment and an opportunity to put patients in contact with people who have personal stories to tell about the decisions for better or worse, which is something that I don’t think we think about enough, you know, when we have both possibilities in mind. So I think that’s a good idea or something to consider, and then a section on support, and if you’re feeling pressure, et cetera, et cetera. What other factors are making this decision difficult for you?

That’s an idea in a very brief and tiny print nutshell about what the general personal decision guide format is, and this is only to give you a flavor of some of these things, but I thought you probably, based on that , need to see something like a real PDA in the wild. So now I’m going to show you some examples from that site that I mentioned already. I think I just went to the searchable list and typed in autism.

And one of the things that came up was a link to a PDA that was developed by Autism Speaks and this other group about who I know nothing.

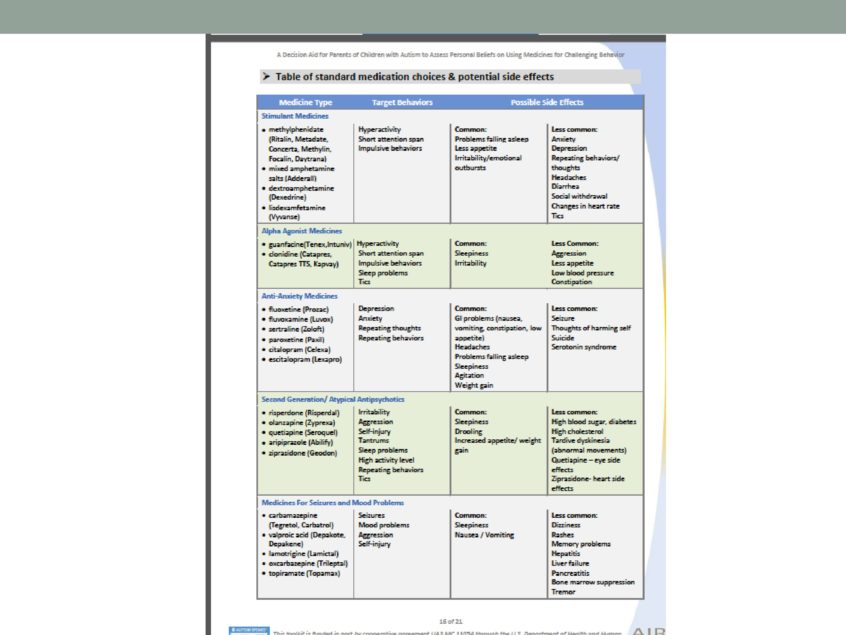

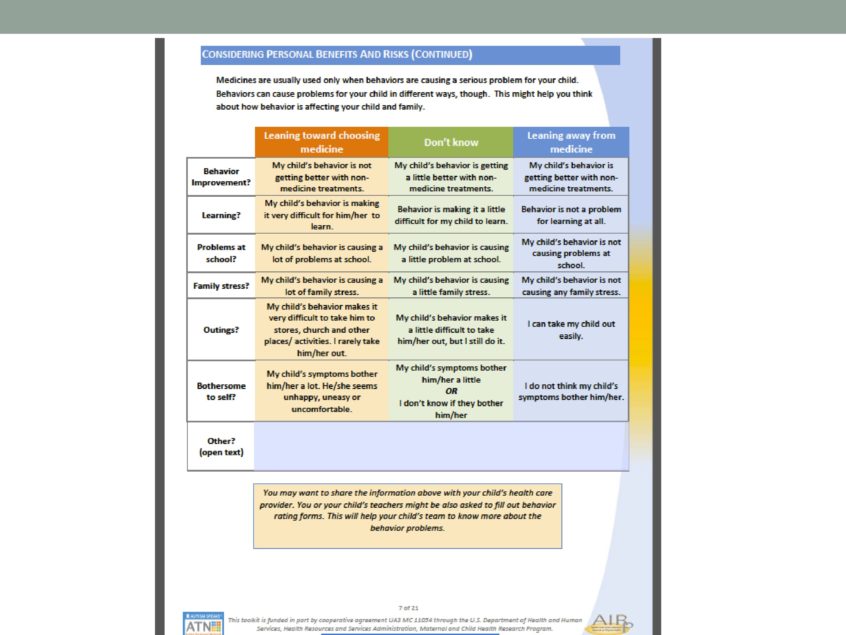

And this is a guide for parents, and the question is people who face a choice about whether to treat their child’s challenging behaviors with medication or not, or alternatives? So this PDA includes sections on information that I’m not going to show you, like, what autism is. You know, the usual things that you would expect to see. How much variability there is in the population. What challenging behavior is. How it’s defined, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. It also includes sections with personal stories by parents of kids who have either been treated with medication or not. I’m not going to show you those, but they’re, I think, really nicely done, for better and worse for each kind of choice, and then they have nice, simple, clear tables showing the standard medication choices, the behaviors their intended to across, and so forth.

So this is an example of the table. It lists big classes of medicines/medications, the target behaviors that they’re intended to treat, and possible side effects, okay? So reducing the target behaviors, balanced by what side effects have been observed, okay? In a really nice, clean, simple, not deluging people with information but trying to make it manageable.

There’s also a section describing the alternatives treatments besides medication. Besides medicine, what are the other options what would be the possibilities besides using medicines.

So some of the things they list there, and see what is causing the behavior. Work with your healthcare provider to find and treat health problems that might be part of the hip behavior problem chronic pain or, you know back of sleep or nutritional issues, digestive issues, stuff like that. You can work with the behavior specialist rather than giving medicine. You can work with a psychologist. You can make a daily schedule. You can get help in caring for your child, all right? So just some alternative possibilities.

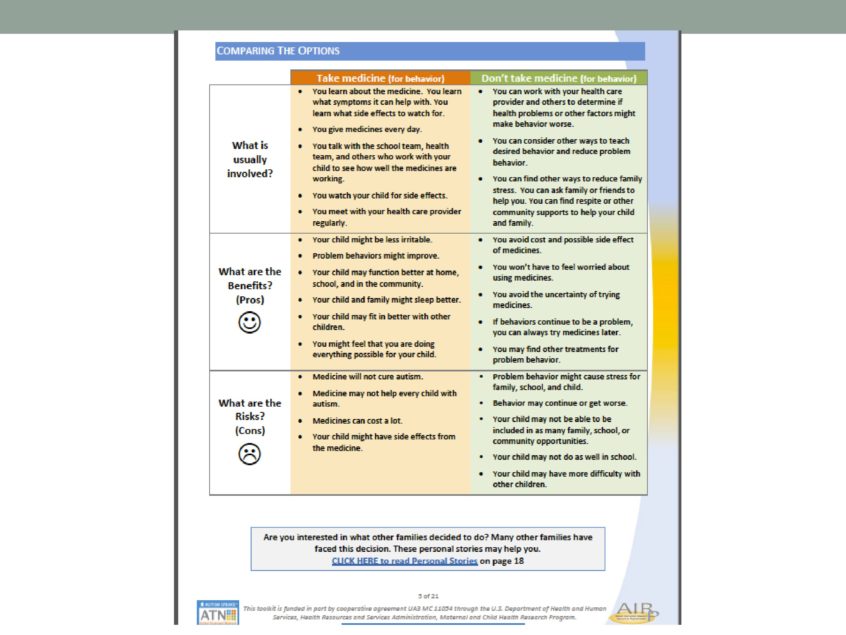

The other pieces of this PDA information in terms of information content. I’ll show you a simple chart that compares the two basics options. You take medication or don’t take medication for behavior. On these three dimensions, what’s usually involved? What are the benefits more the risks, and what’s usually involved is critical because that’s the part that connects with how the family’s daily life is going to change. What the parent has to do. What actually taking a medication is – how they will notice what has to happen.

In the orange column we have take a medication for behavior. What’s usually involved? You learn medicine. You learn what symptoms it can help you with. You learn what side effects to watch for. You get medicines every day. You talk with the school team to see how well the medicines are working. You meet with your health-care provider regularly. If you don’t take the medicine, a lot of the effects of daily life remain the same. You’re still going to be in contact with the school team. You’re still going to be in contact with the healthcare provider, et cetera. Then a list of where the benefits of taking the medication versus not taking the medication? What are the risks, or cons, of taking the medication, of not taking the medication? So some of these, what are the risks, it’s an opportunity, I think, for parents of kids with autism spectrum disorders to be able to say bluntly, medicine will not cure autism. That’s good to be on record. The reason that’s going to be of benefit, you need to clearly understand that at least at this point in time, we don’t have evidence about that.

Then there’s a values clarification section that’s going to look very similar to the personal decision guide.

So, very important to me. You give a five-star rating in each of the boxes. Slightly important to me and not important to me. I think my child may feel better. I think the problem behaviors might improve. I can deal with the side effects of medicine, et cetera, et cetera.

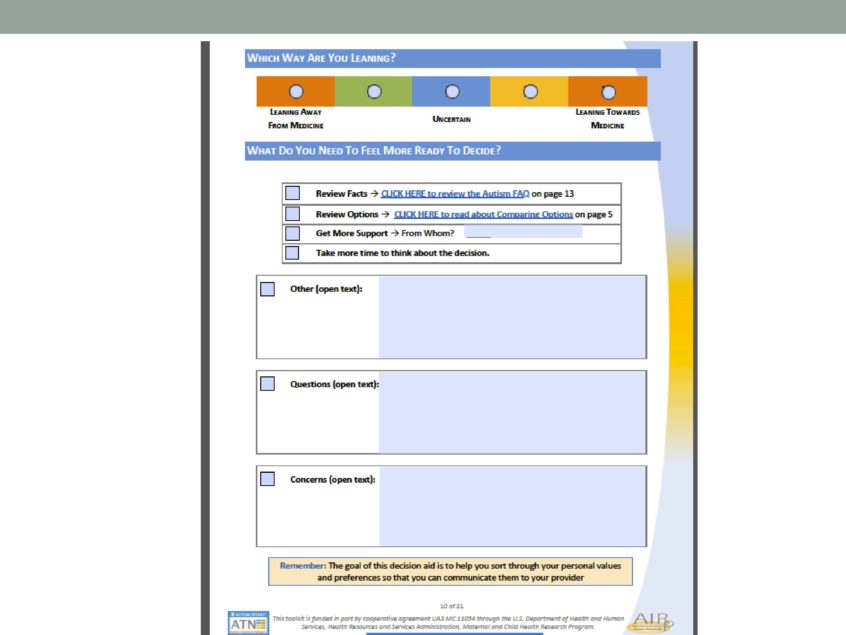

And then which way are you leaning? Again, this looks familiar. Leaning away, uncertain, leaning toward. What else do you need in order to feel ready to make a decision? I need more facts. I need more option information. I need more support, and if so from whom, and I need more time. What are my options?

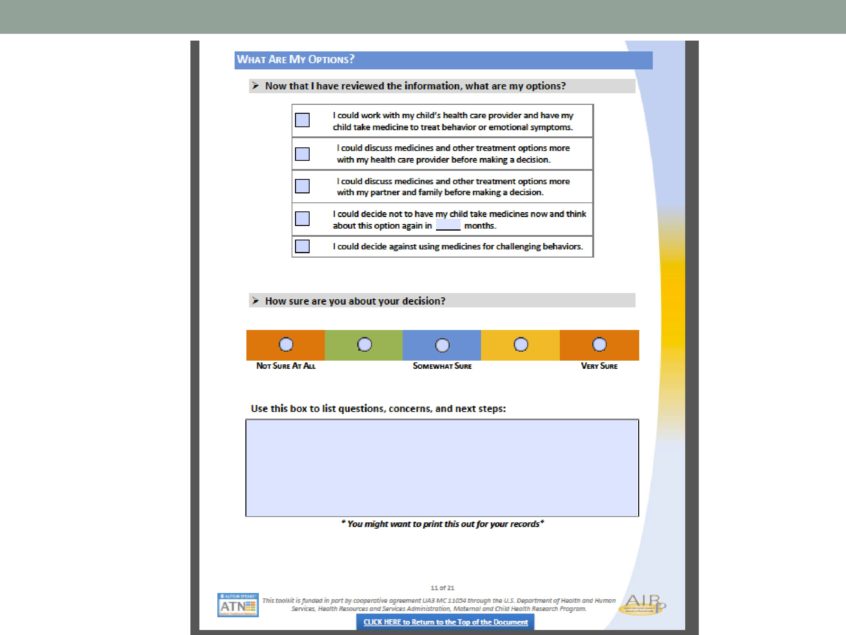

Now I’ve reviewed the information. What are my options? I could, okay, list these, and now how sure are you about your decision?

And then pros and cons. Okay, leaning toward medication. Here’s what would push you toward choosing to medicate and I’m not sure for these reasons, and I’m leaning away from medication for these reasons.

You see the framework is very consistent with the general personal decision guide, but there’s a whole lot of content information that’s been pulled together by Autism Speaks and this other group, so that it’s sort of synthesized and put into that framework so that it doesn’t require – it’s there for the taking.

A lot of other organizations are jumping on this PDA bandwagon, including the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, AHRQ, and so that’s another good website. They’re really just starting to develop PDAs, and they’re using very similar framework.We’re not going to go through, blow by blow, but that’s another place to have a look.

In terms of quality control for PDAs, there’s this International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration, IPDAS, and this started at OHRI. OHRI is really the place where all this got going. So they’re sort of the emperor of the world of PDAs, if there’s such a thing. So they’ve really been interested in — we tell people, “Send us PDAs, and we’ll put them on our inventory so people can search for them.” Just like the one we looked at by Autism Speaks. Okay, a lot of good information there, it would seem, but what is the quality of the information, right? If it’s so simplified, what’s the evidence for all of those, none of that stuff was listed there. So how seriously should we take it?

IPDAS is a group that actually evaluates each of the PDAs that appears on the OHRI site and evaluates them according to these standards, and there are content standards, effectiveness criteria, and generic criteria.

So they go through and actually rate for each of these PDAs that you might pull up and take a look at. At the bottom there is a section in which they explicitly rate the PDA on these various dimensions so you can get an idea of what’s the quality of the information content.

Are the probabilities expressed, as we’ll see in a minute, how probabilities are expressed as an important aspect of having people understand what the potential outcomes of their decisions are. What kind of a development process happened, et cetera. Just to give you a flavor of some of the questions that the IPDAS standards will be asking about each of the PDAs that appears on at least that website, and it’s a good model if you find a PDA at the AHRQ site or you have another PDA proposed by another agency to consider taking a look at it through the lens of these criteria, so that you know basic quality issues. Doesn’t mean that it’s not useful, but it might cause you to make some modifications or qualify some of the statements in a particular PDA. So that was information content.

This is development process. Balanced manner, very important.

And then effectiveness standards. These are just examples of some of the criteria.

So this is how the PDA that we looked at by Autism Speaks actually fares according to the IPDAS review on this same website, and it’s small. So that’s very helpful, as you look at the PDAs that are out there, to not just say, “Hey, this looks like a really amazing thing, and again, really a good idea if you’re thinking about developing a PDA yourself, which I hope you all will, because, my goodness, do we ever need them.

So another interesting set of developments that are kind of fun to take a look at is how we communicate information to patients. So PDAs are basically communication and consultation and collaboration, shared decision making tools. We are the experts in terms of the content, and the patients are the experts in terms of their values and preferences. We have a role to play in terms of how we communicate the content information, and they have a role to play in terms of how truthfully and completely they express their values and preferences.

There’s a lot of interest now in the PDA world about how we communicate a lot of this complicated content information to patients, and it’s early days in this literature, but there’s some interesting findings and interesting studies. The meta-analysis, said if it’s a complicated decision, if you make it too simple, that’s not a helpful PDA. If it’s a complicated decision, having more information, more detailed information actually resulted in better patient understanding and all of those other effectiveness criteria, but I would say here, too, the Three Bears principle applies. You want it to be just detailed enough, and where that sweet spot is for a particular decision and a particular kind of information remains to be seen.

Elwin and her crew put together this option grid to try to simplify women facing either lumpectomy or mastectomy decision-making, and created this by looking at frequently asked questions about the two options that they had encountered in clinical practice and tried to make it nice and clean and simple about which surgery is best for long-term survival. What are the chances of cancer coming back in the breast? What is removed? Will I need more than one operation on the breast? How long will it take to recover? Will I need radiotherapy? Will I need to have my lymph glands removed? Will I need any chemotherapy? Will I lose my hair? So again, starting with what the patients really wanted to know. Frequently asked questions and using that to try to organize a simple, clear chart with answers to those questions, and this might be a study that took eight minutes less time to have these talks with patients.

The other thing that’s interesting is how we talk with people about numbers, communicating probabilities and numeric information. And this whole area, I find it fascinating, and I wish I could tell you I’m in expert in it, because boy do I need help expressing probabilities and understanding numbers.

But it turns out that there’s pretty good evidence that it’s much better to express probability information using natural frequencies, as they’re called, rather than talking in general terms, and to try to put it in a natural frequency in terms of numbers of people and numbers of outcomes.

So sometimes, trials that compare two options will talk about relative risk and absolute risk, and risk reduction, and all these numbers that we can make ourselves understand them, but we’ve gone through statistics classes, and we’ve tried to figure out what they mean, and our patients, you know, saying that somebody who takes a drug is 15 times less likely to develop a joint problem than somebody who doesn’t take the drug, if the drug is supposed to prevent or delay joint problems, 15 times less, if you take, you know, blah-blah-blah, it’s just not very clear.

The idea is that it’s also not very helpful to just say there’s a lower likelihood, or it’s less probable, for example. So putting it in terms of a hundred people who take the drug to prevent this joint deterioration, one person will have their joints deteriorate in the next five years. Of a hundred people who don’t take the drug that’s supposed to prevent that, 15 will develop joint deterioration in the next five years. Okay, it’s all communicating the same information, but that’s sort of explicitly stated and in a natural frequency where you think about, okay, a hundred people with this disease and either taking it or not taking it. So that’s kind of interesting.

I’ll just show you kind of a cool study by Martin et al., and this is where I took this example from, but they did a trial where they explicitly compared just a narrative statement of the probabilities versus pictures of joints deteriorating or not deteriorating versus a pictograph, which I call a dot plot, that shows the hundred people, and the hundred people are one color to start with, and then the people who develop the disease are colored red or something. So they compare the dot plots and the pictographs and then they try the little speedometer example.

So the narrative statement below, one benefit of this preventative drug is its power to slow further joint damage. Research has shown that drug C can reduce the rate of rheumatoid arthritis, joint damage, in most patients by about 85%. Right, you see how unclear that is? It’s, like, my disease will be about 85% less worse? Or less bad? Or what? Hard to interpret right?

And then narrative plus graphic representation of either taking it or not taking it over five to ten years. Then you have the narrative plus natural frequency. So with people who take the drug versus don’t take the drug, there’s a visual depiction of each person’s outcome, based on the best available evidence, and then they have this little speedometer which is how many people get a new joint damage when they’re not taking the drug, which is a hundred, and how many people get new joint damage if they’re taking the preventive drug, which is only about 15.

So they made this all up and tested the four conditions in college students, as well as in rheumatoid arthritis patients. So they were interested in, if you don’t have the disease will you reach different conclusions or be differentially accurate in understanding the progression, and they found that there was absolutely no difference between the two groups in the effects of these different presentation formats. Which is really encouraging because that means that we can probably test some of these communication formats in people who don’t have disease and find out a lot that we can then apply to using with our patients, and everybody underestimated the drug’s benefit. So this wasn’t a panacea. It wasn’t a perfect world, but the people who received narrative and some sort of graphic, especially the pictograph, and the people who had the narrative plus the speedometer little metaphor were more accurate than the people who had narrative alone or narrative plus just the photographs.

So what’s next? This road is leading into a bright new future, right? So let me just stop here and say that a couple of things occur to me, but I bet some things are occurring to you, too. One of the things that occurs to me is that nobody’s going to do our PDAs for us. We’re going to have to do our own PDAs, and so it’s interesting to think about. I’ll speak only for myself. I’m not used to thinking about explicit alternatives or options. I usually have my preferred recommendation, and that’s what I recommend. So I think there’s going to have to be, as we start down this road, we have to explicitly train ourselves how to be less biased and present the information in a balanced way and acknowledging that not treating somebody is a perfectly reasonable option in many cases.

I’ll use the example of an analysis I just did of late talkers in which the question was, does being a late talker increase your risk of a language deficit later on? And they did a big meta-analysis, and the answer is no. There’s no evidence that being a late talker increases your risks of language deficits later on. So to me, that means that I think there’s a lot of beliefs out there and recommendations. Because we want to help our patients, and treatment is often assumed to be the rational choice, but in fact, if we take a look at the evidence, an equally rational choice is to do watchful waiting or not to treat immediately but to monitor and see what happens. Then I think we’d have that talk with our patients more often than we do. One thing that happens if we assume that resources for treatment are finite, is if we’re treating people who actually don’t benefit from treatment, somebody who could benefit from treatment is not being treated. So anyway, we’ve got to do a little bit of changing up our perspective, I think, to actually imagine what these options are, and I think a good place to start would be talking with our patients about the different options and, you know, people who have been told that they should have treatment and have proceeded with it, versus people who have not proceeded with treatment, getting some of these stories, personal stories together, as well as the evidence syntheses. So, that is what I had to say. More of a acquainting you, maybe, with some resources and approaches that I hope you weren’t familiar with before you came to the talk, and I think I’ll stop here and ask for questions or for your ideas.

References and Resources

Björklund, U., Marsk, A., Levin, C. & Öhman, S. G. (2012). Audiovisual information affects informed choice and experience of information in antenatal down syndrome screening: A randomized controlled trial. Patient Education and Counseling, 86(3), 390–395 [Article] [PubMed]

Brinkman, W. B., Majcher, J. H., Poling, L. M., Shi, G., Zender, M., Sucharew, H., Britto, M. T. & Epstein, J. N. (2013). Shared decision-making to improve attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder care. Patient Education and Counseling, 93(1), 95–101 [Article] [PubMed]

Choi, H., Pargeon, K., Bausell, R., Wong, J. B., Mendiratta, A. & Bakken, S. (2011). Temporal lobe epilepsy surgery: What do patients want to know?. Epilepsy & Behavior, 22(3), 479–482 [Article]

Elwyn, G., Lloyd, A., Joseph-Williams, N., Cording, E., Thomson, R., Durand, M. & Edwards, A. (2013). Option grids: Shared decision making made easier. Patient Education and Counseling, 90(2), 207–212 [Article] [PubMed]

Martin, R. W., Brower, M. E., Geralds, A., Gallagher, P. J. & Tellinghuisen, D. J. (2012). An experimental evaluation of patient decision aid design to communicate the effects of medications on the rate of progression of structural joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Patient Education and Counseling, 86(3), 329–334 [Article] [PubMed]

O’Connor, A. M., Bennett, C. L., Stacey, D., Barry, M., Col, N. F., Eden, K. B., Entwistle, V. A., Fiset, V., Holmes‐Rovner, M. & Khangura, S. (2009). Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. The Cochrane Library.

van der Weijden, T., Boivin, A., Burgers, J., Schünemann, H. J. & Elwyn, G. (2012). Clinical practice guidelines and patient decision aids. An inevitable relationship. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 65(6), 584–589 [Article] [PubMed]

Ottawa Hospital Research Institute (OHRI). (2012). Patient Decision Aids. (source for Autism: Should my child take medicine for challenging behavior? A decision aid for parents of children with autism. Autism Speaks & Autism Intervention Research Network on Physical Health).

International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration. (2015). International Patient Decision Aid Standards.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (2011). Research Summaries for Consumers, Clinicians, and Policymakers. Available from the AHRQ Website at www.ahrq.gov (source for Therapies for children with autism spectrum disorders: A review of the research for parents and caregivers).