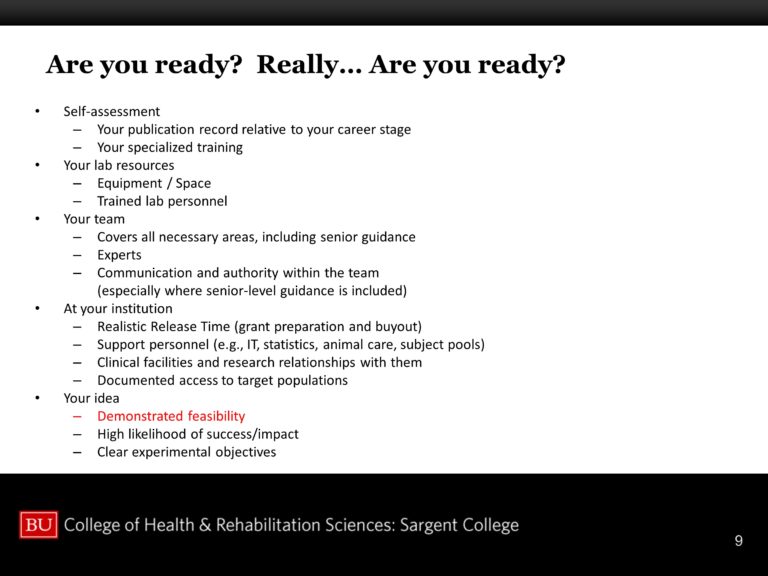

Part 4 of 8 in the “Preparing for Your First NIH Grant” series provides a brief grant-readiness assessment checklist for yourself, your lab, your team, your institution, and your idea

The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

Self-Assessment

So, self-assessment. The most important piece of that is your publication record.

People often look at their publication record and they’re concerned that they’re not ready for this independent award. If you’re concerned, that’s reasonable and maybe just good judgment. But you should seek guidance from an experienced mentor to say, “Yeah, I’ve seen a lot of R03s, and this publication record isn’t going to be strong enough for an R03.” If so, that’s not a problem, there’s some place for everybody to jump in to the NIH funding stream. If you’re not appropriate for one mechanism, you may be appropriate for another mechanism.

You have to consider what specialized training you’ve had. That goes into the specific aims you worked on last night. Where does your training point you? Not “what is it you want to do?” This is “what’s your background, what is your preparation?” What is it that a reviewer can look at objectively and say, “Oh, yes, this person is a good candidate for this project, for this mechanism, for this institute.”

Your Lab Resources

What do you have available to you? What resources are available? What people are available? What mentoring team is available? This, I talked about this yesterday, too.

Your Team

Assembling your team. Don’t be shy about assembling the strongest people you can find. That’s not just people at your institution, but people who are anywhere in the world. When you have people that are not at your site, the bar gets a little higher in terms of demonstrating your logistical connection. But you can do that. You can say, “We have Skype meetings every Tuesday at 2 am to accommodate this person’s schedule in Beijing. But we really need their help.” Demonstrating the logistics can be a really important part of showing that this team is real.

Get those experts on your team. Show that you’ve had communication. And show how the distribution of authority is arranged. You really are the project director, the PI for an R03—or the sponsor really does have control of this team. Everybody’s role is defined and responsibilities are clear. It makes it much more compelling.

At Your Institution

I do want to spend just a minute talking about how you negotiate things at your institutions. Those of you who aren’t at research-intensive institutions, you’re in a tight spot. There’s the expectation that you’ll be productive in terms of grant generation. And why wouldn’t they want to put that pressure on you, they love the cash. They don’t have very many cash streams, and your salary at least is a lot more than they’ll have to pay to buy out—have to pay adjuncts. And the indirects are great. Everything is in the institution’s interest to provide pressure for you to seek external funding. That’s fine, that’s the way it should be—you want to seek the external funding. You wouldn’t be here otherwise.

The pressure that has to go back to them has to say, “Yes, I understand you want me to do that, but I need time to do that.” The difficult spot that sometimes you run into is that if the grant culture isn’t a part of the institution, there can be the expectation that you keep teaching, or that you somehow provide oversight of what was your instructional responsibility, or you keep advising 50 students. There has to be some kind of accommodation, and the review committee is going to take it as their responsibility to make sure your time is protected.

NIH—it’s not a contract, you have to be very careful to distinguish between a contract and a grant—but in this sense you can sort of look at it as a contract that taxpayers are paying for your time. The review committee is going to make sure your time is built in and protected. It’s your job in preparing for the grant to make sure the institutional letter of support reflects an appropriate amount of release time. For a new investigator, that should be paid by the grant. You should release salary dollars, pay for salary in your grant budget, on the order of 20% to 50%. It should be a substantial investment in your time by the funding agency. Your time is the best thing they can buy. They don’t want to buy you a new lab. They don’t want to pay for 400 grad students. They want to buy your time. That’s the most valuable thing on the grant. So you should make a serious commitment to it, and your institution has to back you up. If they don’t back you up, if they push back too hard on that, then there are a lot of institutions out there that would be very happy to add you to their team.

I already talked about clinical facilities and demonstrating research relationships with them and documented access.

Your Idea

So finally, after all of that stuff, then you finally get to talk about your idea. What’s amazing is there’s all this structure you have to build up—logistical structure you have to build up before you can even talk about science. That’s part of this program. You have to learn all of these logistics, all of the culture and the acronyms and the people that you need and all of this non-scientific stuff that you need to support your science.

When you finally get down and get to think about your idea—I think I mentioned this yesterday, that it should be feasible, it should have demonstrated feasibility.

It should have—this is a weird balancing act—but it should have a high likelihood of success. It doesn’t mean this experiment—some people interpret that to mean you should know what the outcome of the experiment is before you do it. I’ve even heard people say that your first aim should already be in the can before you submit the application. That’s not true. People can smell that, and that will not go well. Nobody wants to pay for work that’s already been done. The idea is that you should know your science well enough that you have a strong guess of what the outcome is going to be. And even better, if there are alternate outcomes, if you can say how one alternative or the other is going to steer science in one direction or the other. So, that’s a real bonus if you have strong alternate theories, competing theories.

And then you already did this—because you have specific aims—of having clear experimental objectives.

Preparing for Your First NIH Grant: More Videos in This Series

1. Who Is the Target Audience for Your Grant?

2. How Do I Determine an Appropriate Scope, Size, and Topic for My Research Project?

3. Common Challenges and Problems in Constructing Specific Aims

4. Are You Ready to Write Your First NIH Grant? Really?

5. Demystifying the Logistics of the Grant Application Process

6. Identifying Time and Budgetary Commitments for Your Research Project

7. Anatomy of the SF424: A Formula for NIH Research Grants

8. Common Strengths and Weaknesses in Grant Applications