Guidance on authorship criteria, roles, and order, and advice for avoiding unethical authorship situations

The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

Authorship. That’s the uncomfortable topic that I’m going to talk about. Authorship is important. It’s how we measure our success. It’s how our performance gets evaluated.

Who Is an Author?

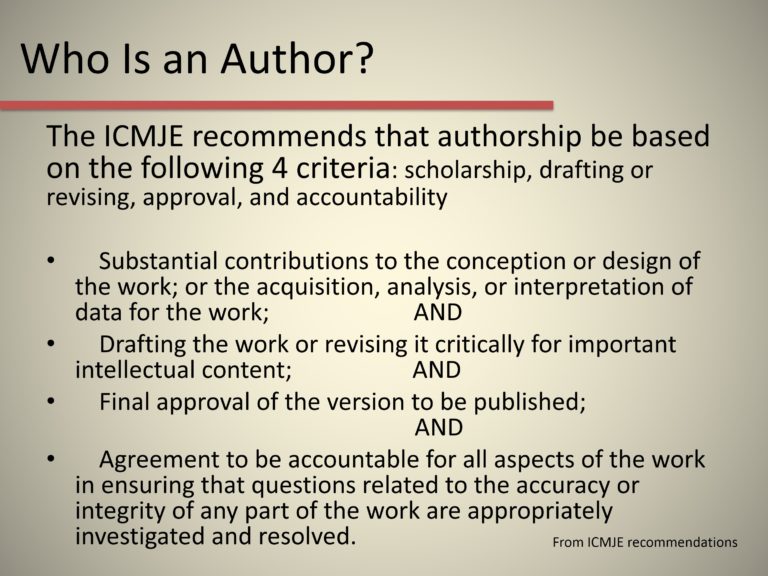

No matter how much we talk about it, there are always going to be grey areas. But in addition to that, there is guidance. The guidance that we most commonly use is the ICMJE which is the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. You can find these recommendations on their website.

Four criteria are required for someone to be considered an author: scholarship, drafting or revising, approval, and accountability.

I would say the first one, substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work—that’s the crucial one. Second is drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content. Third, final approval of the version to be published. And fourth, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

So if we go back to the first one—substantial contributions—for that you already have some grey area. You have to determine what you mean by substantial contributions.

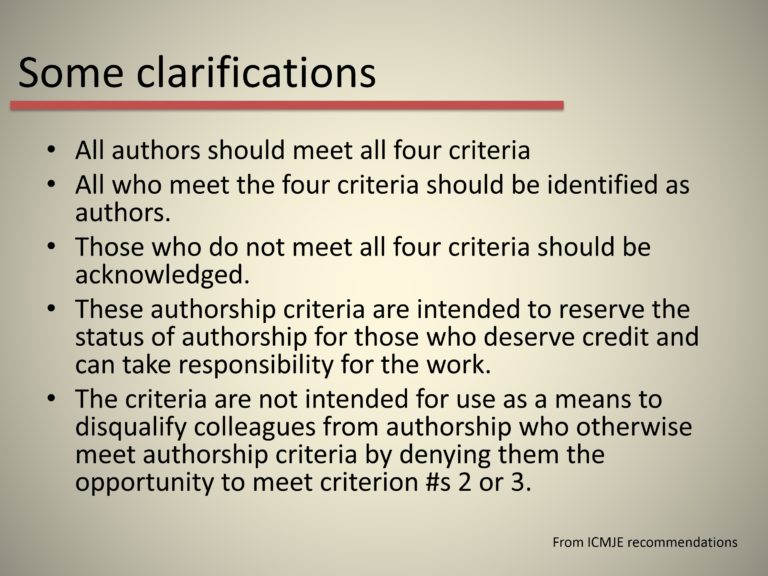

It’s important to remember that all authors should meet all four criteria. And everyone who meets all four criteria should be included as an author.

Those who do not meet all four criteria should be acknowledged if they made other contributions to the paper.

The last paragraph on the slide, that’s important. The criteria are not intended for use as a means to disqualify colleagues. Somebody could do a study, write the paper, not give the paper to one of the people who should have been a coauthor for review—and then say, “Oh, he didn’t meet criteria number 2.” No, you can’t do that.

The important thing is to make sure that everyone who deserves credit is an author, and that there is no one in the list of authors who is not deserving.

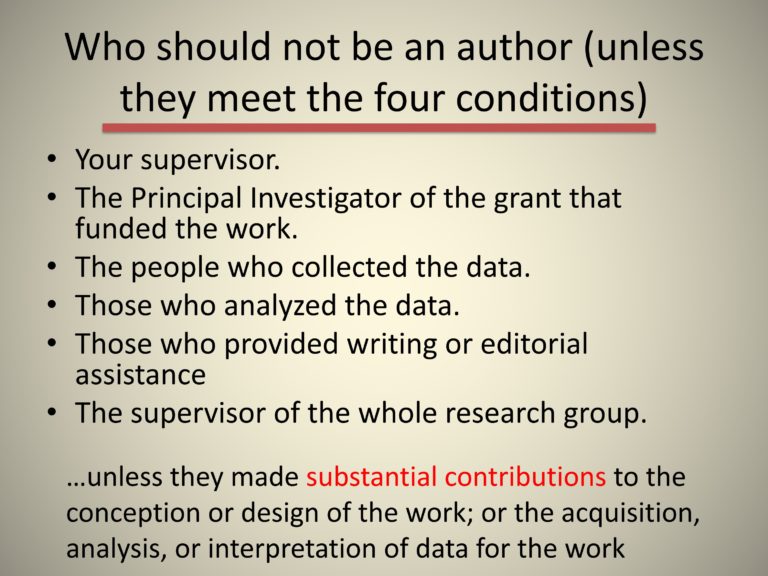

These are some conditions that do not necessarily qualify you as an author. Just because you conduct the study and someone is your supervisor, that does not mean that the supervisor made enough of a contribution to be included in the list of authors.

Being the PI of the grant that funded the work—the mere fact that you contributed money does not mean that you contributed intellectual content. I actually have an example from quite recently. Working with a colleague who is super smart, I agreed to contribute some money to do something specific that we want to do in his lab, which is to develop a rat model of cochlear implantation. He assumed that because I was contributing that money that I would be a coauthor. I told him, “No!” I hope to provide enough intellectual content that I will be worthy of being a coauthor, but he shouldn’t automatically consider me a coauthor because of that.

Data collection does not, in and of itself, justify authorship. Again, this is a grey area. There may be situation where data collection is so difficult and complicated, and requires such specialized knowledge and training, that it becomes a major contribution. But there are other situations where you can easily train a person with brief instructions on how to acquire the data, and then acquiring the data in and of itself is not a part of being an author.

Same thing about data analysis. Or even providing some writing or editorial assistance. In the course of our work, we frequently edit little things for our colleagues. That is not enough to make us authors, clearly.

Being a supervisor for the whole research group. None of these things, in and of themselves, make you an author… unless you make substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work. Substantial contributions being the operative part of this.

Lead Author vs. Coauthors

Coauthors must be responsible for authorship, and must acknowledge that they meet the authorship criteria that we talked about. They have to consent to the lead author that they have reviewed and approved the manuscript. And they are responsible for the content of all appropriate portions of the manuscript.

Of course an individual retains the right to refuse coauthorship, if he chooses. You might think—if you don’t have a lot of time and need something submitted for your grant proposal, and you don’t have time to contact this person who is in Costa Rica on vacation—you might think that it is a nice thing to do to include them. But everybody has the right to decline to be a coauthor, and you cannot add them without their consent.

Unacceptable Authorship

There are different examples of unacceptable authorship, and all of these happen every day.

Once I had a colleague, he’s a super clinician and the chief audiologist in our cochlear implant center, and he told me that he received a phone call from someone in a cochlear implant company offering him to be the first author of a manuscript that they were writing.

What this company was trying to do was obtain the legitimacy of a well-known clinician at a top, respected university, to support whatever they wanted to say. It sounded strange to him, so he asked me what he should do. I said, you don’t need this, it doesn’t make any sense. But that would be an example of a guest, gift or ghost authorship.

A guest authorship—honorary, courtesy, or prestige—is defined as granting authorship out of appreciation or respect for an individual, or in the belief that expert standing of the guest will increase the likelihood of publication, credibility, or status of the work.

Gift authorship is credit, offered from a sense of obligation, tribute, or dependence, within the context of an anticipated benefit, to an individual who has not contributed to the work. That’s something that I’ve seen a lot in my career. I know of many colleagues in junior positions who have complained of this. For example—this is a true case—a graduate student wrote terrific papers for her dissertation. Her papers were coauthored by her two supervisors, also terrific people. When the paper was going out, she noticed that the name of the department chair had been added, and she actually complained to the department chair about it. He was furious. He said that this is the way that we do things around here—when, in fact, according to the opinion of the lead author, he had not participated at all in the intellectual part of the study. That happens to some extent, and it is unfortunate.

Ghost authorship—and this is what happened to my colleague at the cochlear implant center—the failure to identify as an author someone who made substantial contributions. It’s completely unfair and unethical for someone to request to be added as an author just because he is the department chair or the PI. However, it is also unethical to not include someone who actually had a major role in developing the study and writing the manuscript. That person may not care about authorship because he works for a hearing aid company, and he wrote the paper showing brand XYZ and their new noise reduction algorithm is far superior to any other algorithm on the market today. That person can obtain an advantage if all the authors in the paper are independent academics. A reader will interpret the paper differently if they see the name of two engineers and the chief audiologist at XYZ hearing aid company. So deleting the names from the list of authors is also inappropriate. There are several recent cases of this involving the pharmaceutical industry.

Ghost authorship may range from authors for hire with the understanding that they will not be credited, to major contributors not named as an author.

Authorship Order

Talking about grey areas: One important part of authorship is determining what the order will be. In the list of authors there are two privileged positions—first author, and sometimes the senior author has his name go at the end of the paper. At my university, as a senior person I get as much credit for being the senior author as for being the first author.

It’s not always easy to determine who should be the first author. To the extent that it’s possible, these things should be discussed in advance. If they involve a collaboration outside the lab, it’s even more important to do that. With the understanding that these things can change over time, and sometimes you don’t know at the beginning who will make the major contribution to a given study.

There will be cases that you have disagreements. It doesn’t mean necessarily that anyone did anything unethical, but it still leaves people unhappy about their authorship. So the order of authors is a collective decision of the authors or study group. It’s nice when that happens, but it doesn’t always.

In conjunction with the lead author, coauthors should discuss authorship order at the onset of the project, and revise their decision as needed. And hopefully a consensus will be reached—and it is reached in the majority of cases.

This is what I had to say, but we have some time to discuss your questions and specific examples. What questions or concerns do you have about authorship? What interesting cases would you like to bring up—real or hypothetical?

Questions and Discussion

Question: Something I’ve run into, I do a lot of posters or papers for conferences, and I include people who have worked on it in the lab. But then the paper doesn’t get written until much later. How do people handle that, where someone contributed some of the work, but by the time you get to writing the paper, it’s evolved a bit?

That’s another one of the grey areas, right? It may be reasonable in some cases. You want to be as inclusive as possible, without giving away credit. But I think it is possible for someone to have barely just made enough contributions to be a coauthor of the poster, but not necessarily of the more complete paper that comes later on.

Audience Discussion:

- One idea that’s worked well for us, and this comes from working at cross-university consortia where there are a lot of people involved. We have a form that you fill out—we all agree on whether it’s a poster or a student presentation or a paper—and if you’re proposing a poster you fill it all out, and order of authorship is one of the things on there. And it says, if this is intended to proceed to a paper, will that change the authorship? So we do it all up front, and we all sign it. The hard discussion is easier to have before anybody did any work.

Case Example: You talked about famous cases. I just wanted to bring up one very important case that came about in neuroscience involving Nikos Logothetis. Two of his postdocs had collected data and wanted to publish the data once they had left his lab. They wanted to submit it, and they did without his knowledge. He did not want to publish the paper, he did not agree with their interpretation of the data.

It did undergo peer review, and it did get published. But the editors had to write an editorial defending their decision, because they knew he was not in agreement with publication of the paper. But I think this is a good demonstration that these things are not so straightforward all the time. The editors claimed that because it was peer reviewed, the reviewers agreed with the findings of the paper, that it should be published. But I’m sure they are not talking now—the previous postdocs and Logothetis.

I’m not sure if others have thoughts about this, but there is also a question of data ownership in that case. Does the data belong to the postdocs or to the PI or to the institution? Any comments about that? I would go with the institution and the PI over the postdocs.

Audience Discussion:

- Your institution probably has rules about this. At mine, the institution owns the data. Not the PI. Not the postdocs.

- Except for student data. If it was something produced by a student, for a class or something, the student actually owns it. But that may be unique to my institution.

- Often when data are collected in a laboratory, the laboratory itself is an intellectual property. It’s not just that you have this EEG machine with amplifiers and a bit of software. There is always customized software. And the setup of the laboratory involves some intellectual property. For these postdocs to have collected data in a laboratory that really wasn’t theirs, and then not acknowledge what the PI had contributed, the setup of the lab, is really pretty problematic.

We need to go to our break, but I want to finish this by saying something. I only talked about abuse by more senior authors who inject their name in a list of authors without justification. The opposite can also happen. It can be quite common for an inexperienced student or postdoc to say, “but wait a minute, I did everything,” without realizing that maybe this was an experiment that was planned and designed before they even got involved in the study. So it’s possible to make mistakes in both directions.

What you want to do is address these things at the earliest possible time, and with an open discussion among all potential authors.