An overview of definitions, conceptual approaches, design types, and methodology

The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

What am I going to do today? I’m going to define for you what CBPR is, give you a little bit about the concepts and the theory that back it up. I’m going to talk where I can about weaving it in to implementation science, and talk a little bit about designs and methodology and rigor.

Definition

So, what is CBPR? CBPR is a collaborative research approach that is designed to ensure and establish structures for participation by communities affected by the issue being studied, representatives of organizations, and researchers in all aspects of the research process to improve health and well-being through taking action, including social change.

To improve health and well-being. That is an overarching piece there.

So, I’m going to explain is how it’s grounded in theory and practice, but it’s not something that happens haphazardly or casually, and that’s why it works well for many kinds of research.

What do we do when we use CBPR? What makes it unique, is that we meet communities where they are, and we make a place for them at the research table to collaborate with us, so that we do better work.

I’m not going to go through a lot of history. I want you to see that we have a history and that it’s grounded going back decades, and that we build on this strong, rigorous foundation when we use CBPR as our approach.

Conceptual Perspective of the Approach

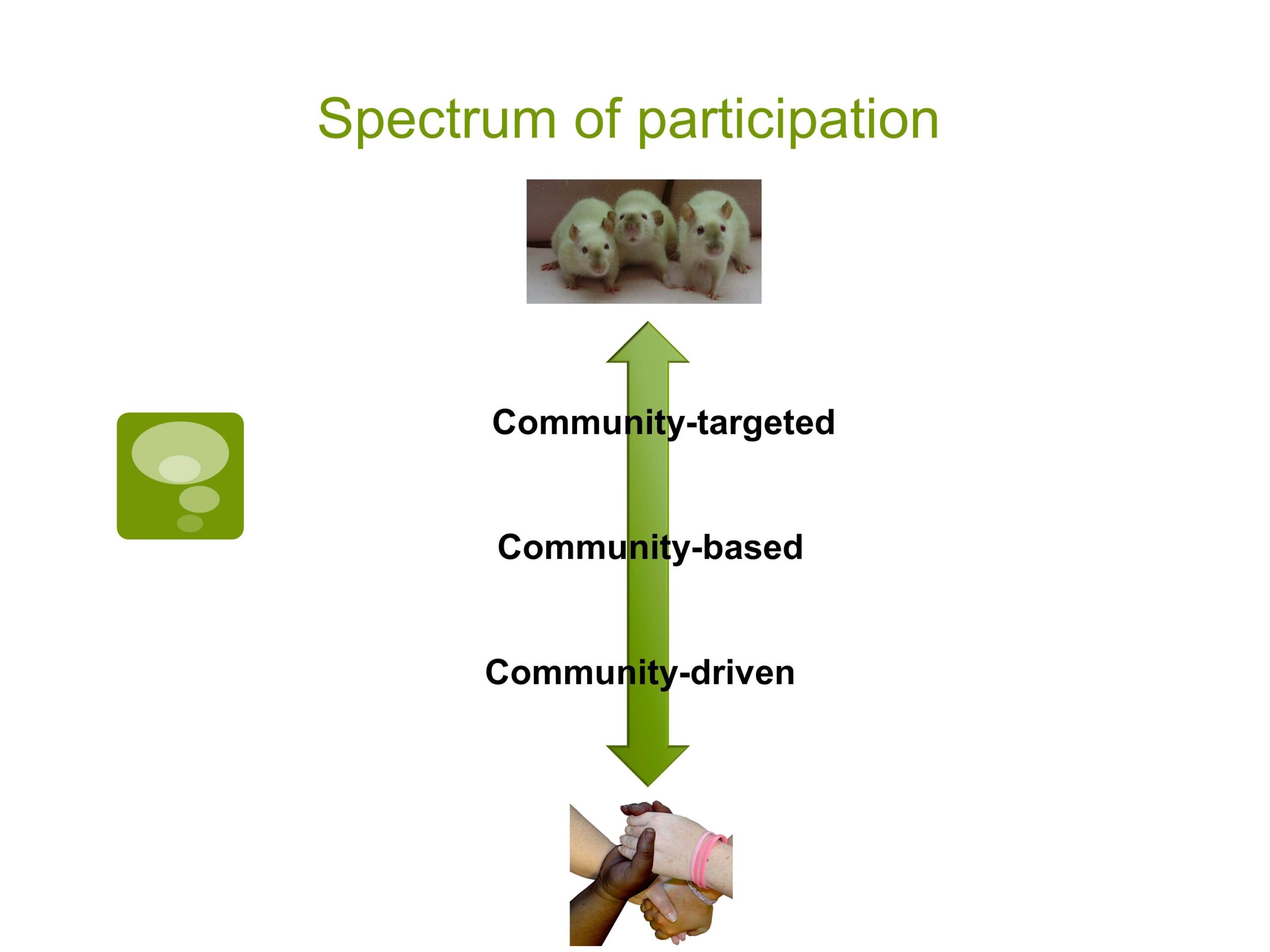

I want you to think of these partnerships as falling into three basic levels.

We’re going to call this first one community targeted research. So, in that one, community doesn’t really have any involvement selecting the research topic. You’ve selected the research topic, you’ve applied for a grant, and you know what you want to do. Maybe the community is involved because they’re helping you with recruitment, for example, and maybe they’re going to help a little bit with dissemination. Community targeted research.

Then we’re going to go up to the next level and we’re going to call that one community based research. That one you’re going to gather input from the community. Maybe you even let them vote a little bit on selecting the topic. And, you may increase involvement of community members at various stages in the research.

Finally we have what we can call community driven research. In community driven research, you’ve got community involvement the whole way through. You’ve got shared power and decision making. Makes some people a little bit nervous, but, you share power and decision making. The focus areas may be generated by the community, and it’s fully participatory.

So, the last one, community driven is not better than the others, it’s not like we’re all trying to get to Nirvana here which is community driven. But, it’s one of the levels of partnership, and you’re going to figure out if you choose to do CBPR, where your work would fit in this.

I like to think of this as a spectrum of participation.

If you’re doing lab research with rodents, you’re not trying to do CBPR. You just throw it out the window, you don’t need to.

But, lab rat research is our anchor at one end, okay, and at the other end is our projects where all the stakeholders are linked together and they’re working as one toward a common purpose.

Somewhere along that participation you can figure out if and where your projects might fit.

I’m going to break down the acronym.

When I say community, who is the community? So, you’re going to reflect very purposefully on who defines it and who represents it, and that is really critical to having a tight project.

Back in 2001 we wrote a paper on improving collaboration between researchers and communities. We asked folks to tell us what does it mean to be part of a community, and they told us that a community is “a group of people with existing relationships who share a common interest. Relationships make community a reality.” That can then be applied in lots of different ways. So, think about who’s going to define the community, who’s going to represent the community, and most people wear many hats from local communities.

Let me give you an example of that. I’m going to use the same example throughout my talk just for consistency. We did a project in nine different communities looking at domestic violence in these various communities. Well, we had some folks who identified as both African American and Native American. They’re wearing a hat and they could have participated in our project in either of those capacities and then we left it up to them, and we said, “You choose, where do you feel like you would feel more comfortable, you would fit better?” So, most people wear many hats for multiple communities, as we all do. And then, you’ll see how that fits in to your project.

We can identify community’s lots of different ways. Maybe it’s a target population. For example, school age kids with asthma. That could be a community that you’re working with. Maybe it’s ethnic or racial groups: Latinos, East Africans, Native Americans. Maybe it’s religious groups. It’s Muslims belonging to a particular mosque for example. It could be a cultural group. Immigrant survivors of family violence is one of the groups that I work with. Or, it could be a professional group which I’m sure a lot of you are already interacting with. Maybe local PTSA groups, New Parents Support Groups, etc. So, there’s lots of different ways to select and identify communities that you might work with on a project to strengthen your project.

Now, let’s look at the B. Where’s your project going to be based? So this, again, is the purposeful question, you want to wrestle with this question. Don’t just default to what is easy. We want to think carefully about the implications of place and location with respect to power and ownership of the project.

Is it going to be housed in your research organization? If it is, what does that say about who owns it? Could it be jointly housed and owned by you and the community? How would you share that? Where would you have meetings?

Where will decisions be made? Will they be made in your office because it’s late at night and you’re crunching data, or you’re writing a proposal and you have to get it out the door? Or do you recognize that you’re going to have to actually put some pieces in to place so that decision making truly can be shared decision making, and is that feasible for you?

Let’s look at the P. How participatory will it be? So, think back to those three levels I showed you a few minutes ago. How do those levels fit your project? Do you want input, or do you want involvement?

One is not necessarily better than the other, but, which one is going to fit better for you?

Do you want participation only at certain specific activities? Maybe they help you pick the project. They help on the design. They help on the analysis, etc. You decide with those communities that you’re working with where are they going to fit? Where’s your project going to fit on the spectrum?

Or, do you want it completely collaborative throughout, shared ownership, and that’s a really hard thing to do but, it’s incredibly strong and powerful when you do it.

Finally, what kind of research are you going to do? Is it going to be community assessment, for example? Is it program evaluation which is what I do a whole lot of? Are you going to be testing interventions, or whatever word we’re going to use besides interventions, now I don’t remember what word I can use. It can even be a randomized controlled research. You actually can do CBPR with RCT research and maybe it’s involving the target community to identify ways to make the research more equitable for treatment and control groups.

And, then finally, is it going to be somewhere, along in there, an implementation science project, looking how to move efficacious treatments from the lab to the community setting.

Where’s the rigor? So, here’s what I want you to know, CBPR is the approach. That’s the approach to the project. You’re methods are the methodology. The rigor comes from that combination, that blending of the methods and the commitment to CBPR. That’s where the rigor comes in. So, you’re not throwing your methods out the window, you’re adding a layer. You’re adding a layer of complexity and density, and community involvement and that’s where the rigor comes in.

And, also I want you to think about quality. Quality isn’t only, are we doing a rigorous, rigid scientific project, there are other ways to measure quality in our work. We can measure it with respect to relationships between community members who are affected by health issues, and researchers working on it. We can measure it by looking at practical outcomes that people can really use and that are sustainable over time. And, we can measure it in terms of enduring consequences. So, I think that’s really important to think about when we talk about rigor.

Case Study

Now I want to give you an example of a project where we applied the theory and principals to doing our research. This was a project a few years ago, and in this project we knew we were going to have to use CBPR to be successful because we were looking at domestic violence across culture. And, it wasn’t something that a team of researchers could just drop in and do. We had to partner to make it work.

I’m going to give you a fair bit of detail on this because I want you to see the kind of choices we made and the real specific examples, and then the subsequent effects of those choices. And, I realize that this may seem like a bigger or more complex intervention project than many of you conducting right now, but I’m hoping it can illustrate how a rigorous approach to CBPR can give you ideas of what you might want to consider down the road.

This was a pilot project where women who had been experiencing domestic violence were organized in to language and culture specific support groups. We had four cultures represented, and they met every two weeks for education and social opportunities. That was the intervention.

The idea came from a community assessment that we had already done that was funded by NIJ. The reason I wanted to tell you that is community based participatory research does get funded. And, the intervention itself was funded by the CDC.

CBPR is going to make more work for you, it is. But, it’s also going to add a layer to your proposals that make them stronger and make them more compelling. So, think about that as well, because NIJ funded us, CDC funded us because we were a CBPR project working on an important issue.

Prior to receiving the grant for this project we had worked with the community based agency, ReWA; Refugee Women’s Alliance, on the assessment portion. So, our relationship with the community was well established already when we did this. We had already laid that groundwork.

After the initial assessment grant ended we held several follow-up meetings to determine next steps. We took the data back to them, back to the community organizations, and we said, okay, what do you want to do with these findings? Where do you want to go with this? And then we said to ourselves, what do we want to do with these findings? And then we said, what can we do together? So, that was the shared choice making, shared decision making part.

Through these meetings we came to a mutual agreement of what an intervention might look like. So, it was a joint decision process of what could we do that would be a testable intervention. And, we wrote the whole grant with their active participation. They were there at every meeting, every step of the way.

Then, once we gotten it and we were moving along, we had to maintain that participatory research. When the advocates themselves begin facilitating these support groups and the intervention, and we were collecting data, we continued to partner in several ways.

We gave them ongoing logistic support. So, we didn’t have the research team over here, and the program team over here, and we didn’t stay in or own little silos, our own little places, and do our stuff. It was a constant feeding and nurturing back and forth.

We had ongoing regular meetings and events.

We disseminated the findings along the way to the program staff, so that they could make changes in their agency, for example, and other programs that they were doing. They could use the findings as we were going along. They didn’t have to wait until the end to have anything meaty to work with. Then once we’d actually done all of our data analysis and such and we were ready to disseminate the final findings from the project, we cleared it with them first. How do these look to you? Do you think what we’re saying makes sense? Is there something we haven’t considered that we need to go back and look at? So, that really strengthened our analysis and our writing.

So, collaboratively what did we really focus on? The idea for the intervention came from the women who were interviewed in the assessment. It was their idea of where we could run with this. The women who had actually been interviewed in the assessment, they came up with the curriculum that we use, so they helped develop that intervention curriculum.

This is a really important piece that staff and participants shared: language and culture. If you don’t have folks on your team that represent the cultures that you’re researching, find them. Find them, and figure out how you’re going to partner with them. And, that’s going to be a give and take process, but as we all know, those days of researching the “other” – we as anthropologists really know this and we have to admit it with humility – the days of researching the other are over. They need to be at the table.

Then support those program folks. They are already doing full time jobs and we’re adding to their load when we bring them on to our research projects, they need to be supported, and that has to be a complete commitment from us as researchers, and that’s how we learn as well. It’s reciprocal.

So, in conclusion about this case study, you may have to make concessions to your research approach, your research design. That’s a tough one.

I want to give you a very specific example. As part of our evaluation, we use a well-tested psychological assessment instrument. But, we were working with one of the groups who were Somali women, and we were told you can’t talk about sexual abuse. You can’t use those questions, not an option. And, we said, well you know, we’re working with this well tested psychological assessment instrument. And they said, can’t talk about that, and we had to defer to them. We had to work collaboratively and defer to them and find other questions to use, or decide that we couldn’t use that portion of the instrument, period.

That back and forth negotiation is critical and we all make concessions. They make concessions every day. They’ve been making concession in the community every day that we’ve been researching them without having them at the table. It’s our turn to make some concessions.

And, sharing a vision is critical. Meeting before our project even began, to make sure that we are all on the same page, that we all have the same vision – that was really an important, ongoing piece of, also, our sustainability for the project.In the end, the goals of the researchers and implementation science are to move successful treatments from the lab to the community. Community members want the same thing. It’s about finding that common ground.

Benefits & Limitations of CBPR

Okay, so where’s the benefit? Why do this? What does CBPR give us?

What it’s going to do is give you an understanding of that research issue that problem in situ. We’re hearing directly from folks who are affected by the problem and need the solution. They become part of the process. So, while some researchers are concerned about sharing power with a target population and having biased findings – don’t know if you ever hear that – when we apply a rigorous structured approach to our partnership, we find that we actually understand the research issue better. We can interpret the results better because we’ve partnered and we’ve got those folks helping shed light on the issue from their daily lived experience.

It also provides real benefit to the community, and I think that’s a huge one. We’re all in this business because we want to help people feel better, right? We want them to feel better and we find, that when we use the CBPR approach, that we can convey real benefit to the community, and we do better work. I’m a better researcher because of it.

Okay, limitations. It’s not going to be a straight path. You’re research path may take unexpected directions which can be really exciting, actually. You may end up going in a way you never even considered but, what that means is, resources, time, money, support of your funder, you’re going to need more of all of those. I can say, without exception, a CBPR project always takes longer.

Which I think is really interesting because a couple of folks talked about increased efficiency. I’m not going to talk about increased efficiency with CBPR, but, do I like the end point better, yes. That came up to me as I was listening to other folks talking about how do we get more efficient? How do we get more efficient? That’s not what I’m pushing for. I’m pushing for, how do I do it better.

Is it right for everybody? So, ask yourself and your team some questions. Do we see the non-traditional value this is going to add to our team? Are we ready to adapt and adjust to expectations and demands from non-researchers? If we don’t have team members with cultural competence, are we willing to bring those on? And, I want to, I was telling someone at lunch, we were talking about this, and I was saying, you know, I also teach people how to do qualitative methods. I teach students, I teach professionals. And, at some point in every training, I look out at the group, usually a smaller group than you, but, I look out at the group and I say, you know what, there are some of you who are never going to be comfortable using qualitative methods. You’re just not. You don’t want to talk to people. You don’t want to have conversations with folks, that’s not the kind of researcher you are, and that’s okay.

There are some of you who may never be comfortable with CBPR, that’s okay. But, others may be seeing where this could, you know, lend something to your team, to your approach, and I’m going to urge you to know yourself, and then push yourself a little bit.

Is it right for every project? No. So, what you’re going to want to think about there is who are the communities we might work with? Are there communities to work with? If there really aren’t communities to work with on your topic, I don’t know what project that would be. If someone comes up with that they get a prize at the end of the day. But, if there aren’t communities to work with then it’s not the right approach. Think about what level of community involvement you might want. Is it throughout, is it at certain stages, etc.

And then how do we sustain it? This one’s key because, I have to say I don’t think I’m going to do a CBPR project unless I can see a path of sustainability. I might not know where I’m going to get the money. I’m not sure who’s going to do it, but, in bringing community folks to the table, I’m making a commitment to them, and I can’t walk away from that at the end when I’ve written my report. So, if I can’t see a possible path of sustainability, then maybe CBPR isn’t the right approach for this particular research topic that I’m thinking about.

Getting Started

So, how do I get started? Start where folks are. Look at assets. Everybody is being, is tired of being told what’s wrong with them. We are all, and especially if you’re poor, you’re from a different language community, you’re from a different culture community, you are tired of being told what your problem is.

Let’s flip it around. Bring folks to the table and talk about the assets that you know that they’re bringing to be on your team, start with that. And then speak really clearly and honestly with folks. Everyone responds well to that.

So, I’m not going to go through these. I want to just put these principles up here. These are the principles that guide our work, and if you do choose to do more CBPR work and you can fall back on these principles, they are really going to ground you in a successful approach as you bring folks to your research table. Thank you.

Questions and Discussion

Audience Questions

Question: What are some of your recommendations to people who are looking for funding for this type of research?

I don’t know your field as well, so I don’t know as much about who would normally fund you. But, I guess what I would say is, whoever you would normally apply to for funding, you’re adding a layer of quality to your work. So, I wouldn’t go elsewhere to look for funding, but I would pitch this as improving the project that you’re going to do. Does that make sense?

Amy Donahue, Division of Scientific Programs, NIDCD/NIH:

I would say NIH funds it. But, one thing I was just going to say for those interested in this: there are several listservs that you can get on. I probably get, I can’t tell you how many emails, and there are people out there that are very engaged in this, and they have ongoing dialogue, and so, there’s a lot of chat, and opportunities to engage in conversation about this if you’re interested.

Kirsten Senturia:

Thank you. And also, Renee was reminding me there is a group Community-Campus Partnerships for Health, originally out of the University of Washington. There are folks representing it all over the U.S, and that’s another really dynamic organization to link in with.

Question: We engaged in a lot of collaborative work with community partners around school readiness. We had all of these conversations going, and they were suggesting research projects that were interesting, but that we had no expertise in. It wasn’t that we had an agenda at the beginning, but that the things they were asking for were so far outside of our expertise, that we just couldn’t bring any resources to bear on their questions. So, how do you move those relationships into ways that actually build towards something that you can really address and get your hands around?

That’s a great question. And, the fact that you’re even having that dialogue with those folks, says a lot about your commitment. You’re having an open conversation over time with them, and there’s nothing wrong with turning to folks in the community and saying, you know what, I know nothing about that. That’s not my field. But, you know what I do have that you don’t have: I’ve got my feet in the university. I’ve got that connection, and I can work with you to find folks doing that.

Folks out in the community don’t know how to get their foot in the door. They don’t realize, for a number of reasons, the whole culture of the university. They don’t realize that there are people at the university that might actually be dying to work with them. So, make that connection, but I also think they can then provide that same service to you. And you could say, I love that topic, I know nothing about it. Here’s what I’m interested in, can you connect me to some of those folks? So, I think it kind of becomes a networking process in a way.

Question: Have you had any experience with communities where participants may not want to be open about being a member of the community, but they want to help you out with your research. For instance, transgender, lesbian, and gay communities. If you have people that want to help you but say, I don’t want them to know who I am. How do you handle that?

I haven’t had that experience because the folks that I’ve ended up working with have been in a place where they wanted to stand up and take that stand. But, certainly, it’s like anybody else I guess who might be advising you on the side, whether they’re advising you because they’re an expert in some scientific method, or some other reason. They’re not going to come to every meeting. So, I think you could turn to folks like that to be an advisor to you, to be a sounding board. But, I guess when you’re thinking about the public face of your project, you’re going to be very, very discreet and careful, and that person, or those folks aren’t going to be in that public face in any way.

A separate Q&A Panel including this presenter is available online: Implementation Science Summit: Panel Discussion with Renee Boothroyd, Michael Weiner, Robert Horner, Kirsten Senturia & Matthew Kreuter

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2009). Activities using community-based participatory research to address health care disparities. AHRQ Pub. No. 09-P012. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/factsheets/minority/cbprbrief/

Baker, E. A., Homan, S., Schonhoff, S. R. & Kreuter, M. (1999). Principles of practice for academic/practice/community research partnerships. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 16(3), 86–93 [Article] [PubMed]

Bradbury, H. & Reason, R. (2003). Issues and choice points for improving the quality of action research. In Minkler M. & Wallerstein N. (Eds.). Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Chrisman, N. J., Senturia, K., Tang, G. & Gheisar, B. (2002). Qualitative process evaluation of urban community work: A preliminary view. Health Education & Behavior, 29(2), 232–248 [Article]

Eisinger, M. A. & Senturia, K. (2001). Doing community-driven research: a description of seattle partners for healthy communities. Journal of Urban Health,78(3), 519–534 [Article] [PubMed]

Fals Borda, O. & Rahman , M.A. (1991). Action and knowledge. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. San Francisco: Herder & Herder.

Hicks, S., Duran, B., Wallerstein, N., Avila, M., Belone, L., Lucero, J., Magarati, M., Mainer, E., Martin, D. & Muhammad, M. (2012). Evaluating community-based participatory research to improve community-partnered science and community health. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 6(3), 289 [Article] [PubMed]

Israel, B.A. , et al., (Eds.) (2003). Community-based Participatory Research for Health. New York: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Israel, B.A. , et al., (Eds.) (2005). ). Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. New York: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Lindamer, L. A., Lebowitz, B., Hough, R. L., Garcia, P., Aguirre, A., Halpain, M. C., Depp, C. & Jeste, D. V. (2009). Establishing an implementation network: Lessons learned from community-based participatory research. Implementation Science, 4(1), 17 [Article] [PubMed]

Koné, A., Sullivan, M., Senturia, K. D., Chrisman, N. J., Ciske, S. J. & Krieger, J. W. (2000). Improving collaboration between researchers and communities..Public Health Reports, 115(42038), 243 [Article] [PubMed]

Krieger, J., Allen, C., Cheadle, A., Ciske, S., Schier, J. K., Senturia, K. & Sullivan, M. (2002). Using community-based participatory research to address social determinants of health: Lessons learned from seattle partners for healthy communities. Health Education & Behavior, 29(3), 361–382 [Article]

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. Journal of Social Issues, 2(4), 34–46 [Article]

Metzler, M. M., Higgins, D. L., Beeker, C. G., Freudenberg, N., Lantz, P. M., Senturia, K. D., Eisinger, A. A., Viruell-Fuentes, E. A., Gheisar, B. & Palermo, A. (2003). Addressing urban health in Detroit, New ork City, and Seattle through community-based participatory research partnerships. American Journal of Public Health, 93(5), 803–811 [Article] [PubMed]

Minkler, M. & Hancock, T. (2003). Community-driven asset identification and issue selection. In Minkler M. & Wallerstein N. (Eds.). Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Minkler, M. & Wallerstein, N. , (Eds.). (2003). Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Senturia, K., Sullivan, M., Ciske, S. & Shiu-Thornton, S. (2000). Cultural Issues Affecting Domestic Violence Service Utilization in Ethnic and Hard to Reach Populations. Public Health-Seattle & King County. Available at http://kingcounty.gov/healthservices/health/data/injury.aspx

Sullivan, M., Bhuyan, R., Senturia, K., Shiu-Thornton, S. & Ciske, S. (2005). Participatory action research in practice a case study in addressing domestic violence in nine cultural communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(8), 977–995 [Article] [PubMed]

Sullivan, M., Kone, A., Senturia, K. D., Chrisman, N. J., Ciske, S. J. & Krieger, J. W. (2001). Researcher and researched-community perspectives: Toward bridging the gap. Health Education & Behavior, 28(2), 130–149 [Article]

Wallerstein, N., Oetzel, J., Duran, B., Tafoya, G., Belone, L. & Rae, R. (2008). What predicts outcomes in CBPR? In Minkler M. & Wallerstein N. (Eds.). Community-Based Participatory Research for Health (2nd Ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Wells, K., Miranda, J., Bruce, M. L., Alegria, M. & Wallerstein, N. (2004). Bridging community intervention and mental health services research. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(6), 955–963 [Article] [PubMed]